Justin Mah: In what way did this eight-month road trip inform your work, and would it be accurate to describe your photographs as a kind of artful documentation?

Scott Conarroe: The wonderful thing about making photographs is that I’m obligated to go out and actually be in different places. Without undue coyness, the trip was the work, and the photographs are, as you put it, “artful documentation.” In a way, the elegiac tone read into these pictures is as much about driving as it is about train travel. There is a tradition of photographers, from the earliest geological surveys to Robert Frank to Stephen Shore, heading out on grand exploratory road trips. When I was doing “By Rail” and gas was more costly than ever before and the term “carbon footprint” entered common parlance and my old van was making uncomfortable sounds, it struck me repeatedly that the window for this type of adventure is likely closing.

JM: From the outset of your trip, did you proceed with a clear intention of the kind of images you wanted? Or were these scenes that you discovered while travelling and felt needed to be captured?

SC: I didn’t begin with a thesis or an inventory of sites to illustrate my position. I began with a vague interest in the subject of railways, and was compelled by curiosity. This project was definitely shaped by the railway’s proximity to highways. Tracks typically run alongside the road, making them an integral and constant part of a driver’s-eye-view of the landscape.

JM: Railway tracks connect your photos together, whether in images of the open prairies in Saskatchewan or a monorail station in Miami, Florida. Why use the railway as a connecting motif? How did this idea even come about

SC: In 2006, I noticed that tracks were often finding their way into my pictures of other things. They were so consistent in my projects from Vancouver and Halifax and London that I couldn’t ignore a rather intense, albeit sidelong, interest I have in railways. In “By Rail,” the tracks are a “unifying device” in that a range of geographically and culturally disparate environments are seen as a cohesive statement, because each photograph has a piece of railway somewhere in the frame. In a way, this is as true across the physical landscape as it is in the photographs. Miami is a profoundly different place than somewhere like Cochrane, Alberta, and yet a railroad has the same dimensions and construction in each place. There are variations in language and currency and time throughout this continent, but train tracks illustrate a certain type of constancy.

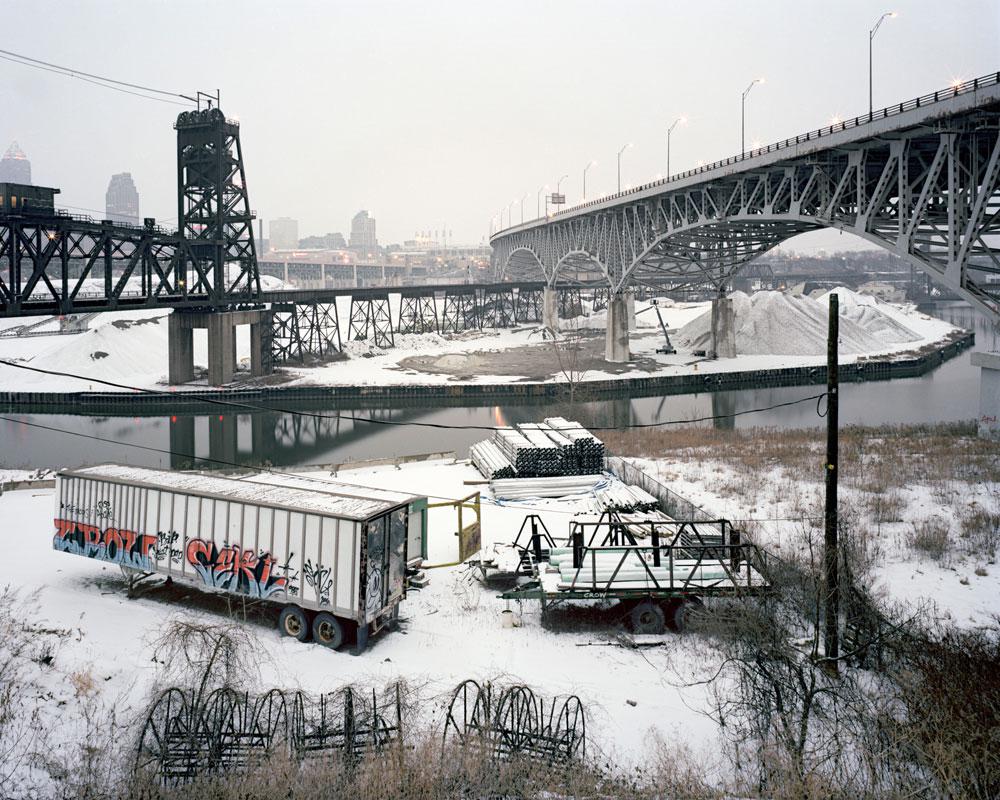

JM: Your images were shot on an classic 4 x 5 camera, and often in long exposures, up to the 15 to 20 minute range for Canal, Cleveland OH and Cul De Sac, Hawthorne CA. Can you discuss your choice to shoot in long exposures?

SC: I use long exposures for a number of reasons. The pragmatic explanation is that they are necessary in the subdued light and deep depth of field that I prefer. Conceptually, I like that scenes change continuously while I photograph them, that they look different at the beginning of exposure than at the end. Long exposures increase a photograph’s autonomy because the truthfulness of its negative doesn’t portray a specific instant that appeared a certain way, it portrays a compilation of moments; they underscore the camera’s roles of abstractor and editor as well as recorder. And long exposures introduce an element of chance into the precision that view cameras are capable of.

JM: The sky features quite prominently in your photographs, illuminating the landscape below in a manner that seems painterly. I suppose this is another reason for you choosing to work in long exposures?

SC: The painterly effect you describe has to do with latitudes of light. I tend to work with sky that’s about as close to dark as it is to bright; when the tonal transition from sky to landscape is less abrupt than we are accustomed to seeing in photos, the visual sense of unity is greater. I suppose it is slowness and deliberateness in the process that sometimes comes across as painterly.

JM: On a personal level, your photographs—the outcome of an eight-month adventure—must resonate strongly with you?

SC: On a personal level, “By Rail” is my first mature body of work. Someday, I hope to look back and enjoy “By Rail” for its charming naiveté, but right now it is involved with so many breakthroughs in my career and personal life that I have trouble considering it apart from them. In 2008, when the bulk of “By Rail” was shot, my long-term relationship disintegrated, I was received as a guest at some very fancy institutions, I was detained as a possible “terror threat,” I bathed in rivers and oceans and truck stops and hot springs, and I lived in the same van that I did as a ski-bumming tree-planting kid a decade ago. A lot happened in my world and that’s all tied up in this project for me. (1026 Queen St W, Toronto ON)

Scott Conarroe Canal, Cleveland OH 2008 Courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery © Scott Conarroe

Scott Conarroe Canal, Cleveland OH 2008 Courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery © Scott Conarroe