Born in Newmarket in 1983, and based in New York since 2008, Ryan Foerster has become internationally renowned for his messy, abstract and arguably punk-rock approach to (formerly) pristine photographic processes.

Foerster’s process involves adding debris to printing plates; leaving photographs out on his roof, or in the rain; and weighting down photo prints with Sudbury mining slag.

Foerster is of course far from the first innovative Canadian photo artist to have made his mark in New York. Here, American critic Bob Nickas speaks with Foerster about this, and other things.

Bob Nickas: In the mid-’80s I was aware of two Canadian artists in New York—Vikky Alexander, originally from Ottawa, and Alan Belcher, from Toronto. They were friendly and smart, each working with photography that wasn’t necessarily camera-based, with photo-murals and photo-objects. It never occurred to me to ask why they came to New York. That’s what younger artists did back then, and still do. Many of the artists here are from somewhere else. The way that Vikky and Alan looked at pictures—as representations, as constructions—fit in with and helped define that moment. They were thought of as New York artists. They were part of the scene. Alan had co-founded Nature Morte, which was one of the best galleries in the East Village. There were other Canadians, photo-based artists in particular, who only came to New York for shows. The first time I saw works by Rodney Graham, Ken Lum, Jeff Wall and Ian Wallace was in 1985 at 49th Parallel, which was the Centre for Contemporary Canadian Art in New York. So they were definitely “imports.”

I also wouldn’t have thought to ask Vikky and Alan, “Why did you leave Canada?” I’ve never asked you. Maybe now’s the time.

RF: I left because I was feeling frustrated in Toronto. Moving there from the suburbs was really eye-opening at first, but by 2005 I wasn’t getting much from it. I lived there for three years and thought: this is not working. I needed to see more art, meet more people and get more involved. Everything I was excited about was coming from New York. I had been in some group shows in Canada, but it wasn’t until I told people I was going to New York that I got offered a solo show there. It added to my realization that I had to leave. And then another 10 years would go by before I was offered a show in Canada.

BN: That was the time-out penalty! But consider yourself lucky, because by then you had developed your ways of working, equally refined and experimental. In fact, there’s a full loop from where you were in 2005 to where you are now. Leaving things to chance, bringing earlier pictures back into the mix—and pictures, for you, represent lives and experiences—has been a way to move forward as you look back. In a sense, you reflect on the present, whatever’s on hand, and sometimes it’s the past, both lost and found.

A lot happened in the 10 years you’ve been here. In that time I met a number of Canadian artists through you—Elaine Cameron-Weir, Bozidar Brazda, Ben Schumacher, Rochelle Goldberg, Shawn Kuruneru, Lukas Geronimas. Counting you, that’s already three times as many artists as I knew in the ’80s from Canada. How do you see this shift with these artists, who I know are all friends, in your time?

RF: We’re taking over! Actually, it was pretty gradual over the years. Even though we’re all from Canada, most of us became friends in New York. When I first got here, everyone would introduce me to other Canadians, which was annoying. But in the end it was helpful. There’s an automatic connection when you’re from the same place and trying to get at something new. Bozidar was the only artist I knew from Toronto who was already living here. He was a bit older, more established, and really open, talking about art and ideas. There’s this sense of camaraderie, helping each other out. At first there was a lot of drinking and joking around, which didn’t seem specifically Canadian. But I remember Mike Egan from Ramiken Crucible joking that we were the Canadian mafia, and he couldn’t go out with us because he couldn’t keep up.

BN: Too much Canadian Mist whisky.

RF: Which I’d never heard of back at home.

BN: People tend to meet in art school and then move to New York. I’m thinking of the CalArts crowd—which included Jack Goldstein, who’s originally from Montreal, by the way. Although they’re all very different artists, they were seen as coming out of that milieu, banded together. But you and your friends don’t have that in common. “School” started for you when you got here. And while there’s common ground visually and intellectually where the CalArts artists are concerned, I’m not sure the same can be said for the artists who’ve come from Canada in recent years. There’s no set curriculum or similar indoctrination, and of course we’re living through a time when there aren’t movements anymore.

RF: Even though Jack Goldstein was part of this group, he had an outsider persona. He skated around that even before he left the art world. I always like artists who are part of something and are also doing their own thing. Agnes Martin and Philip Guston, both Canadians, parts of scenes but separated from or rejecting certain styles. Moving to New York and meeting people definitely sped up my schooling. I was always against art school. I thought it was unnatural. I can’t speak for everyone, because most of the artists we’ve mentioned ended up getting MFAs. I had no idea MFAs even existed until I got here. I really wanted there to be a group that came together—just not from within an institution. We got together by chance, just being from the same place, having similar references and experiences growing up.

BN: Although school offers a sense of community, community may already exist, or is encouraged. John Baldessari was one of the influential figures at CalArts. By the mid-’80s, a number of his students already had careers more successful than his. When he was asked about his approach, he said that he got the better students to teach the others.

RF: Finding people whose way of thinking you respect, you learn just being around them. If I think of the artists who came to New York when I did, and since, even if there was no set curriculum that we all went through, there are similarities to our work, and between ours and other generations of Canadian artists. It’s kind of embarrassing to say, but definitely there’s a way that we deal with space or a sort of landscape that I’m sure has some connection to being Canadian.

This spotlight article, adapted from the Fall 2016 issue of Canadian Art, has been generously supported by the RBC Emerging Artists Project.

Ryan Foerster, Untitled Backside, 2010. Unique C-print, 35.5 x 27.9 cm. Courtesy Cooper Cole.

Ryan Foerster, Untitled Backside, 2010. Unique C-print, 35.5 x 27.9 cm. Courtesy Cooper Cole.

Ryan Foerster, the Sky is Falling (compost print), 2014. Unique C-print , 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy Clearing, New York/Brussels.

Ryan Foerster, the Sky is Falling (compost print), 2014. Unique C-print , 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy Clearing, New York/Brussels.

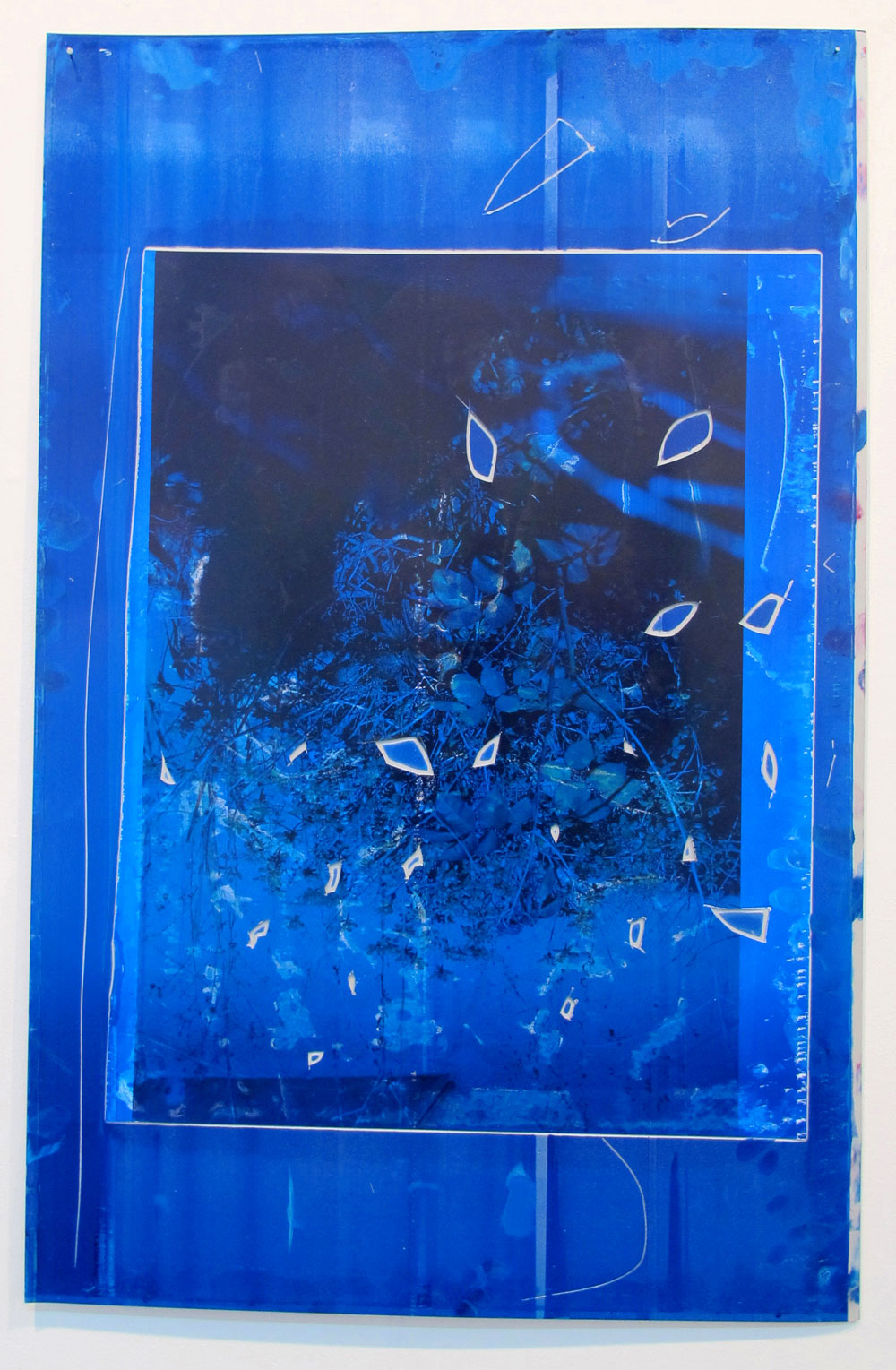

Ryan Foerster, Self Shadow Garden (cyan printing plate), 2012–14. C-print mounted on aluminum with ink, 88.9 x 58.4 cm. Courtesy Clearing, New York/Brussels.

Ryan Foerster, Self Shadow Garden (cyan printing plate), 2012–14. C-print mounted on aluminum with ink, 88.9 x 58.4 cm. Courtesy Clearing, New York/Brussels.

Ryan Foerster, Hurricane (Julie Shower), 2006–13. Unique C-print with debris, 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy Clearing, New York/Brussels.

Ryan Foerster, Hurricane (Julie Shower), 2006–13. Unique C-print with debris, 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy Clearing, New York/Brussels.