When artist Rodrigo Marti introduced me to a project he was participating in—a residency at Toronto’s Trinity Square Video, where he had been invited expressly for the purposes of not making work—my interest was immediately piqued. Itching to find my way into Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens’s strange proposition about un-productive artistic labour, I was propelled by an almost morbid curiosity: If they were intent on not producing artwork, what would they ultimately show?

Questions of product and productivity underlie Is there anything left to be done at all?, Igbhy & Lemmens’s residency/video/installation project which wrapped up this past weekend at TSV. For just over a decade, the Montreal- and Durham-Sud–based artists (who are partners in life as well as in art) have been investigating the potential of mapping abstractions onto lived human experience. The duo recently debuted Visions of a Sleepless World, which runs to June 1 at La Bande Vidéo, as part of Manif d’art 7, the Quebec City Biennial. That work explores pharmaceutically-induced sleeplessness as the dystopian outcome of high-productivity professional culture, investigating the cognitive effects of sleep deprivation. I spoke to Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens in April about their project at TSV, and the current state of professional culture both in and out of the art world.

Alison Cooley: Let’s start with this idea of a corporate model of high-performance productivity. What’s the climate of that now?

Marilou Lemmens: The way we approach this question is from a historical perspective. For a certain time we’ve been interested in the transformation from an economy based on industrial modes of production to economies based on post-industrial modes of production. We’ve been looking at how practices of labour and the organization of labour have changed with those transformations.

Artistic practices represent a field of work where a lot of the characteristics that began to emerge in post-industrial production were actually present beforehand — the emphasis, for example, on collaboration, creativity, and self-motivation. But nowadays artistic practices actualize many of the characteristics of contemporary forms of work. So that was a perspective with which we developed the current project at Trinity Square Video.

Richard Ibghy: The counterpart to that was looking at how artistic practices also emulate the high-productivity careerist approaches that take place in other sectors of the economy. Many intellectual forms of labour have people identifying with what they’re doing, looking to improve their social status through their labour and trying to actualize themselves through work. People are thinking of productivity not only during the time that they’re at work, but also outside of work, which raises a lot of questions about quality of life and being able to enjoy moments during which they are not being productive.

Basically, we were curious as to what would happen if we could suspend that pressure to be productive, which, to a large extent, is internal. The pressure might originate from the exterior, but we, as labourers, have internalized it to the point where we want to work hard, we want to read this book or that essay because we want to produce better work.

This emphasis on productivity, touching all aspects of life, only tends to be suspended when we sleep. But even then, maybe eventually with pharmaceuticals people will be able to extend the amount of hours that can be spent working…

ML: That’s actually happening already, if you look at the number of students or working people who have a lot of demands in terms of work hours, many might use stimulants, whether it’s over the counter simple things like coffee and tea, or pharmaceutical drugs.

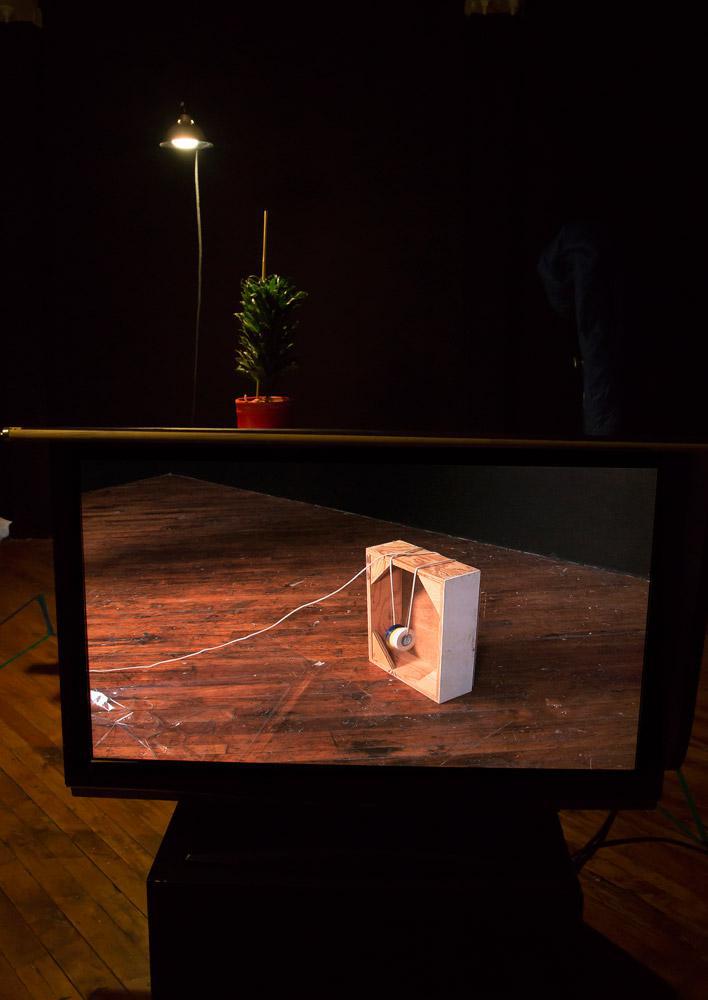

RI: For the residency at Trinity Square Video, we invited people with different artistic practices— Justine A. Chambers, who is a choreographer and a dancer, Rodrigo Martì, who engages in sculptural installations but also community-based art, Kevin Rodgers, who works in expanded-sculpture and Ryan Tong, who is the singer of the hardcore band S.H.I.T. We asked each of them to engage in what moves them without trying to develop anything, whatever that might be– for example, in the case of the choreographer—anything that may be considered a choreography or a dance…

AC: You mention collaboration, and the sense that collaboration has been co-opted by a corporate model of co-production of things. On the other hand, it’s also an artistic strategy that is often used to resist individualism. How do you think about collaboration in your practice?

ML: The first part of this question is very interesting to me—how collaboration has become valued in the world of labour in a post-industrial economy. That’s something that we were thinking about in the fall, during a residency in Basel. We looked at different corporations that have their headquarters in and around Basel, and the strategies that they use to increase collaboration at the workplace.

One of those companies designs office furniture. For more than three decades, they have been developing a whole set of ideas about life at work, and how to structure space, how to use furniture, how to divide space and open space to facilitate collaboration. These same ideas were also being used as an incentive by a pharmaceutical company in Basel, to attract people to come and work for them.

In the end, collaboration becomes another way of maximizing production in an office, or in any kind of work environment where information and communication are what make it possible to create an innovative product.

AC: And in your own work?

ML: As an artist duo, I think the way we work is very simple. We just work together all the time. When we engage in artistic activities with others then the nature and the form of the collaboration has to be reinvented and negotiated.

In terms of working at TSV with our collaborators, the invitation was quite simple. The proposition was, if you are interested, come and workshop the possibilities of unproductive labour, and see with us what can be the generative potential of engaging in a creative practice while keeping the intention to remain unproductive in mind.

It was important for us to give our collaborators a lot of autonomy, so we tried not to impose a predefined model of collaboration, so that it would really start with them and how they wanted to approach the questions we posed for them.

RI: We had already addressed this notion of productivity in previous works, but we had explored it in our own way.

By inviting others to explore this question with us, we were able to broaden our understanding of the subject. Our collaborators pointed to contradictions in our proposition and complexified the whole question. They brought different strategies to attempt to work unproductively. For example, one collaborator tried to focus on the notion of circularity, of returning, always, to a certain point as a means of avoiding development. Another collaborator practiced interruption—that as soon as they felt they were moving towards something, they would interrupt their action with something else that moved them in another direction. Each person brought their own way of approaching unproductivity.

AC: What I find really interesting about this project is pushing back against the notion of an outcome, or a product or a reward at the end. But you were also filming these actions. And so, in some sense, the video is a product…

ML: I wouldn’t say that. I understand that there is something that remains of what was done, but the video is not the product of the residency. The actions that we engaged in were not undertaken or staged to lead to a video production. They were undertaken and valued in and for themselves. The value of the process is the process. The recordings that we made are traces of this process.

Yet, I agree that there is something paradoxical in presenting fragments of the explorations that occurred over the residency in an exhibition when the process is supposedly valued in and for itself rather than as a means to an end. It’s a question of the orientation of an action.

RI: That’s also a discussion that emerged with some of the artists that we worked with. We were trying to explore action in terms other than productivity or goal, but when you get down to it, everything can be broken down into means and ends: “I need to go to the bathroom, so I will get up and walk out the door.” How can I not think in terms of a goal?

AC: So, even the most minor actions can be thought of as goal-oriented, and I think we can think about labour in the same way—there’s a certain point at which anything is labour, there are all kinds of intangible labour. Does creating this framework of inaction or failure help us conceptualize what artistic labour is?

RI: Failure is an important aspect of what we’re trying to do. The notion of success and failure falls within the paradigm of goals and objectives – you either attain them or you don’t. We are trying to escape this paradigm altogether. If what you do does not partake in the logic of success and failure, then I think that there is still something left to be done. But what?

When we were working with Justine Chambers, she pointed to something very interesting. She was working on an idea that came spontaneously, and eventually she stopped. When we asked her why she had stopped, she said because at one point she just stopped caring. That was very interesting for me. She didn’t stop because “the piece” was finished, she didn’t stop because she was done rehearsing something or because she had managed to get some movement right, nor did she stop because it was time go on to something else… She had been developing something that was meaningful to her, and then at the point when it was no longer meaningful, she just stopped. The idea of caring was central—you can engage in a practice in order to produce something, or you could do it because you just care and you’re not really thinking about where it might lead.

AC: In other work of yours, there’s a failure for complex ideas to adhere to economic models. Or, in some work, you’re trying to conceptualize ideas within economic frameworks that maybe they don’t apply to—for example, works like The Prophets (2013), or Supply and Demand for Immortality (2011), the site-specific piece you created for the Sharjah Biennial. That failure is sort of humorous—is there a sense in which this butting-up against productivity in this work is mocking of those corporate models?

ML: I would say no.

RI: I would say no too. The inherent failure of a model– whether academic or conceptual—to contain the complexity and richness of human experience is very important in our work. We try to materialize, through the body and through action, a lot of these abstract principles, and we tend to gravitate towards what falls through the cracks. In both of those works, that is a part of it.

But I wouldn’t say mocking. For example, in Real failure needs no excuse (2012), a video in which we engaged in similar questions of un-productivity, there’s something humorous about the way we go about performing within a workplace. We worked with objects that are ordinarily oriented towards efficiency and maximizing productivity–fax machines, file cabinets, etc.– but we engaged with them in ways that you’re not meant to do. There is a humour in that.

ML: That video also had a sense of irreverence, more maybe than humour or mockery. In the case of the residency at TSV, we didn’t engage with our subject with a lot of humour, though there were times when we were playful in the way we approached actions and collaborated together. There was a lot of play. But I didn’t get a sense that there was humour in what we were doing. There was something rather serious about the whole process.

RI: Part of the contradiction that I faced as we engaged with our collaborators was feeling satisfaction or dissatisfaction after certain activities. At such times I realized that our premise was kind of bogus, or at least that it was very difficult to put into practice: despite my intentions, I couldn’t rid myself of my expectations for certain things to happen.

It really is internalized– we’ve learned to be productive so thoroughly that it’s as if we’re hardwired. This whole dimension of internalization has a seriousness to it that probably prevented us from being too silly.

AC: Perhaps part of the reason it wasn’t so easy to be silly was that actually it’s quite hard to divorce yourself from the process of production. It demands a lot of conscious attention…

RI: It was hard. It was hard for us and then it was hard for the people who worked with us. But I think because it was so difficult, there was a rewarding feeling with each collaborator. We appreciated their generosity and I think they also felt that their time not-producing was productive!

This interview has been edited and condensed.