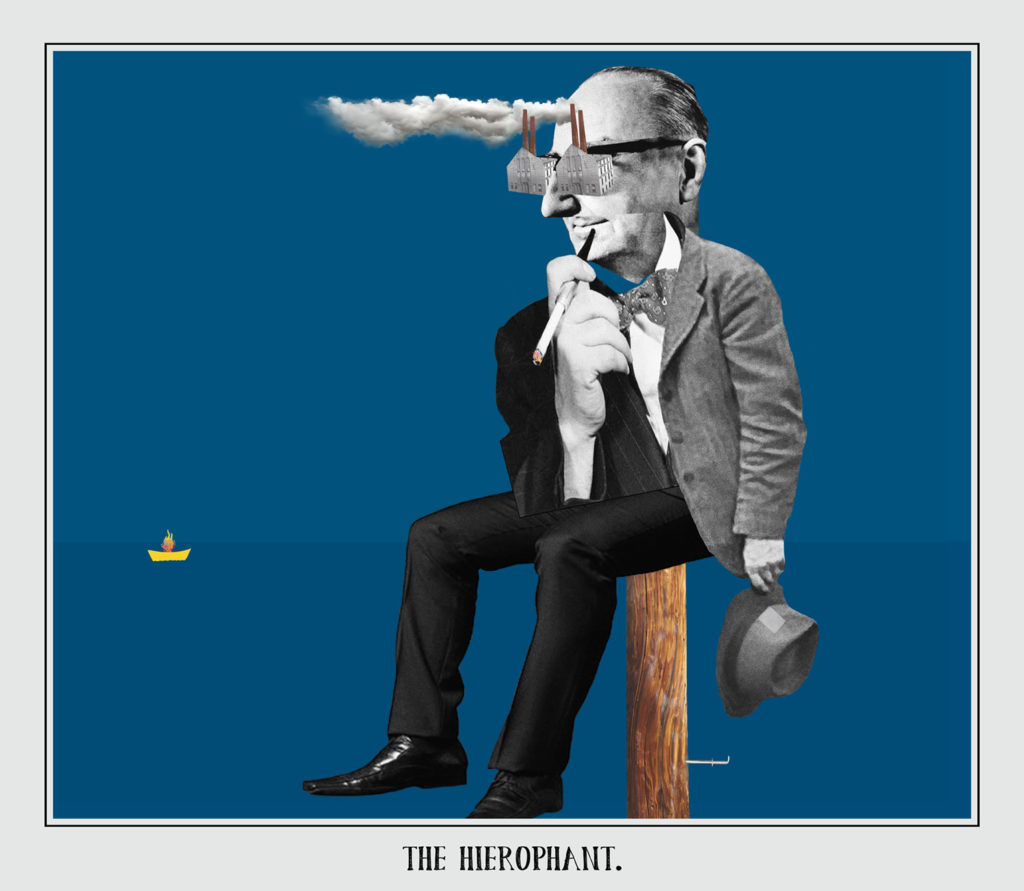

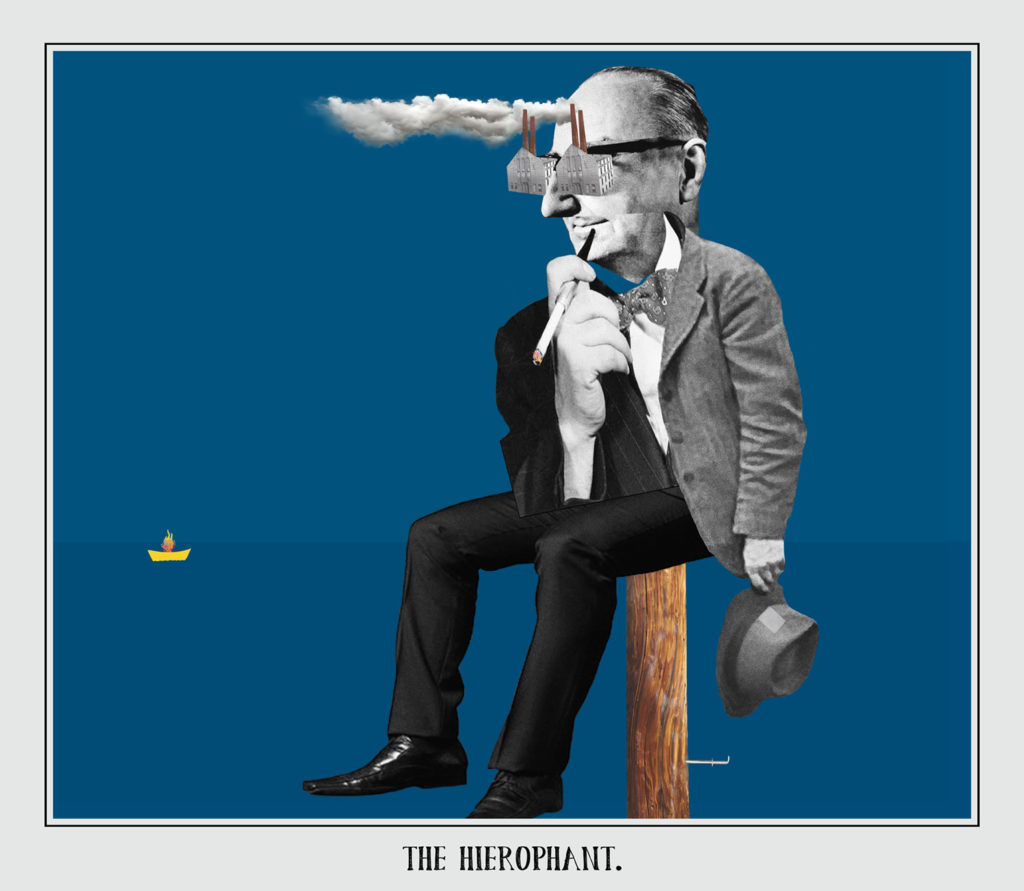

The Chariot as an old Pontiac, driven by bedsheet-masked mummers. Joey Smallwood as the Hierophant, with a smoking cigarette in hand and two sets of factory smokestacks as eyes. A half-dozen old silver butter knives speared into the side of a saltbox house as the Six of Swords.

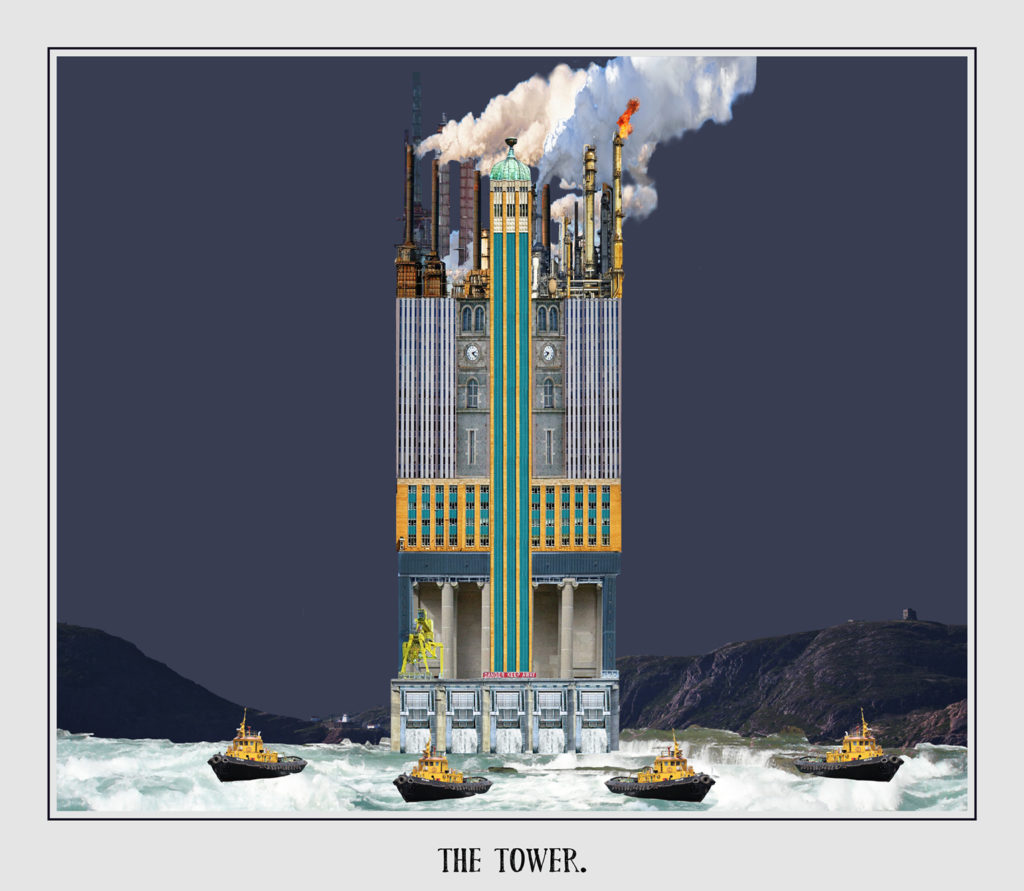

These are some of the evocative, highly vernacular images that Newfoundland and Labrador artist Rhonda Pelley has created for her exhibition “The Fever,” currently on at the Rooms in St. John’s. The exhibition takes regional truths, and myths, as the jumping-off-point for a unique tarot deck—one where steel Hydro towers stand in for the medieval castles of many traditional decks, and where small pieces of lichen, rather than vast European forests, provide a guiding motif.

After seeing the show earlier this year, and being intrigued by its imagery, I met Pelley at her apartment on Cochrane Street in St. John’s for an interview. There, next to a large bay window and an oil lamp set on an old wooden table, surrounded by blue-green walls, artworks by Pelley and friends, and with a tortoiseshell cat occasionally stalking the room, the artist told me more about the origins of this work, and where she sees it going in future.

Rhonda Pelley, The Hierophant, 2018. Digital photo-collage. 47 x 55 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Rhonda Pelley, The Fool, 2018. Digital photo-collage. 47 x 55 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Leah Sandals: There is so much specifically Newfoundland and Labrador lore and imagery in “The Fever.” What is your history in this place?

Rhonda Pelley: I was born here. I spent my first two years on Gower Street, just down the road, in my grandmother’s boarding house. My mom lived there, and then my dad stayed there. When he came in from Bishop’s Falls, he got a room there and the rest is history with them.

We moved to BC when I was 2, because my dad went to art school in Nelson. Then we came back when I was 13, and I didn’t like it at all! [Laughs.] It took me a really long time to like it.

I found some good friends in high school, though, and we became politically active. In my early 20s, myself and a friend travelled around Newfoundland interviewing women who had worked in the fisheries. It was during the moratorium. And that’s when I fell in love with the place.

LS: So you are much more embedded in this place now than you once were. And you have various bodies of work. But the one that’s up at the Rooms right now is part of a tarot deck based in Newfoundland and Labrador iconography—some of which is very recognizable to people who are familiar with this region, and, well, not recognizable to people who are not. How did you begin this project?

RP: Vicky Chainey Gagnon and Mireille Eagan from the Rooms offered me the space, and said I could do whatever I wanted. I spent 8 months unsure about what I was going to do. Then, I said, I think I’ll do a tarot reading for Newfoundland and Labrador. So I did that in about 3 months; I thought about it for a long time, but it happened really close to the deadline.

LS: And why tarot in particular?

RP: I read tarot cards. I’ve studied tarot for most of my adult life, for a lot of different reasons. It’s a visual language, a symbolic language. The cards have different elements of human experience attached to them.

The cards also tell stories, and I’m a very narrative-driven person, so that had a lot to do with it. Originally, I started as a writer. I used to take the writing and exhibit it visually. Then, I gradually moved into photography, and started compositing my own photographs. Then I gradually moved into traditional collage and working with images that were not my own, which really freed me up.

Tarot is very popular these days, and sometimes I wonder about that. I think it might be due to anxiety—it might be that people are looking for an alternative way to connect. Tarot, for me, is about connecting with yourself: it has a deeper connection that isn’t just intellectual and information-based. And I think many of us are living in an over-intellectualized, over-information-based life right now.

LS: You have 16 cards so far, and you are working on completing an entire deck. Have you ever made a deck before?

RP: No, but I’ve always wanted to. Since I was in my early 20s, I’ve always wanted to make a deck. And yes, there is a lot of imagery there that is very particular to Newfoundland and Labrador, but the experiences, I think, are very universal. Political experiences too.

LS: Can you give me an example? Maybe Joey Smallwood as the Hierophant?

RP: Funnily enough, I have a really hard time understanding the Hierophant, and I had a hard time deciding what to do with Joey. To me, it’s a very patriarchal card, and has elements of religious zealotry to it. And Joey was our “savior” who brought us into Confederation and the modern world; he was very keen on industrializing here and getting away from the traditional ways of living with the fishery.

Joey’s sort of the beginning of the modern-day-era boom-and-bust cycles that we’ve had; we tend to fall for charismatic leaders that put all of their eggs in one crazy basket and it blows up in our face—and it happens over and over again. That relates to Muskrat Falls and the dislocation of Indigenous communities as well, which I also wanted to address in the deck. So this particular “tarot reading” is about looking at our cyclical nature, at the things that bankrupt us, and that ultimately the people have to pay for.

LS: And the Three of Swords is three butter knives going through a piece of hard tack—a very Newfoundland food. Can you tell me more about that?

RP: Well, the Three of Swords is a card of heartbreak in the Tarot Deck. It’s about the history of poverty in Newfoundland that very much hard tack is a part of. The silver butter knives are sort of representative of the higher classes—the merchants and merchant relationships that we’ve had here, and that still exist in a lot of ways.

Rhonda Pelley, The Tower, 2018. Digital photo-collage. 47 x 55 cm. Courtesy the artist.

LS: Which cards are you happiest with in terms of how they turned out?

RP: I love the High Priestess. In this version, the priestess is the Veiled Virgin, which is a sculpture at the nunnery here next to the Basilica. It’s an amazing sculpture. Absolutely beautiful. The high priestess is female power, and about using your female power. The women behind are actually dancing on a picture of the Basilica ceiling, flipping male-dominated religion.

LS: And of course Danny Williams is in the deck.

RP: Yes, he’s in the Emperor. Actually, he’s in there twice. The Emperor is made up of most of our leaders at the podium, pontificating. The face is a composite of Danny and Brian Peckford—who got [financially disastrous cucumber growing enterprise] Sprung Greenhouse on the go here in the 1980s—and Joey Smallwood.

LS: You have been in the gallery at least once a month, talking to visitors. How have people responded?

RP: Newfoundlanders have responded to it amazingly well. Those who aren’t from here have more difficulty. For example, I had The Fool holding a cucumber—even one of the curators didn’t know why that was. But the Newfoundlanders know, and they burst out laughing right away.

Some things people say are really insightful, and I learn from them. Judgement is a card that shows a woman holding a tray of talking mouths—the mouths come from those men at the podiums, too, all those male leaders talking and campaigning. The woman holding the tray is standing in front of the Colonial Building.

A man in his early 80s saw that card and told me he thought it was a tray of dentures. He had lived in the outports, he told me, where the dentist would come one year to pull teeth, and the next year to bring the dentures.

LS: So what’s down the road next, do you think?

RP: I imagine I will be working on the full deck for at least a year, because there are 78 cards in a deck. I’m also still interested in the work as a kind of resistance piece. It’s sort of investigating what the power structures are, and bringing it back with a hope that, if you look at power structures in a certain way, maybe it will be easier to confront them—and change them.

This interview has been edited and condensed.