Interdisciplinary artist Bea Parsons’s solo exhibition “Peyak,” titled for the number one in Cree and held at McBride Contemporain in Montreal this fall, explored identity, self and oneness through the creation of a series of monotype prints. Parsons—who studied art at New York’s Columbia University and at Montreal’s Concordia University — began producing the series of eight prints in early 2020, but as she made the prints and the year progressed it became increasingly clear that this was not to be a normal year. Midway through the series, Parsons’s print studio, Atelier Circulaire in Montreal, had to shut down due to the pandemic. When she was able to start working on the series again in the summer, the pandemic had permeated all aspects of life. By the time the exhibition was able to open in September, phrases like “social distancing” and “Zoom meeting” had become the norm. In an interview with Canadian Art, Parsons reflects on “Peyak” and the impacts of the pandemic.

Canadian Art: What was it that inspired you to create the works in “Peyak”?

Bea Parsons: Since moving back to Montreal [from the States in 2017] I started going back and forth between sort of learning Cree and learning French, taking what I know as a native English speaker and just moving the elasticity of my brain and thinking about what I am as a person. I have an Indigenous mother. I have a dad with a European background. I have very fair skin. And I can feel very compartmentalized, depending on the context in which I’m operating. I move in and out of understanding my own identity. And sometimes it can be very frustrating. I think a lot of people with similar backgrounds can identify. So for me, I like the idea of just really starting and learning this language and the number one, peyak, is the first word I memorized, and when I came up with this series I was thinking about just being one thing.

For me, monoprint was the most accessible printmaking method. It’s very conducive to my painting practice, so I can use all the same painterly gestural mark-making and tools. And what I found with this process that I love is working in black and white, removing colour from the equation, more narrative images started to bloom. I was becoming a lot more of a picture maker telling stories. And that really changed my practice. I continue to work in this medium and it allows me to work quickly with ideas a lot faster than painting. And that taps into the kind of verbal narrative part of my brain. When I’m working with colour and painting and the slower process involved in front of a canvas, it’s a lot less verbal for me. The storyteller in me comes out a lot quicker when I’m working in this direct method.

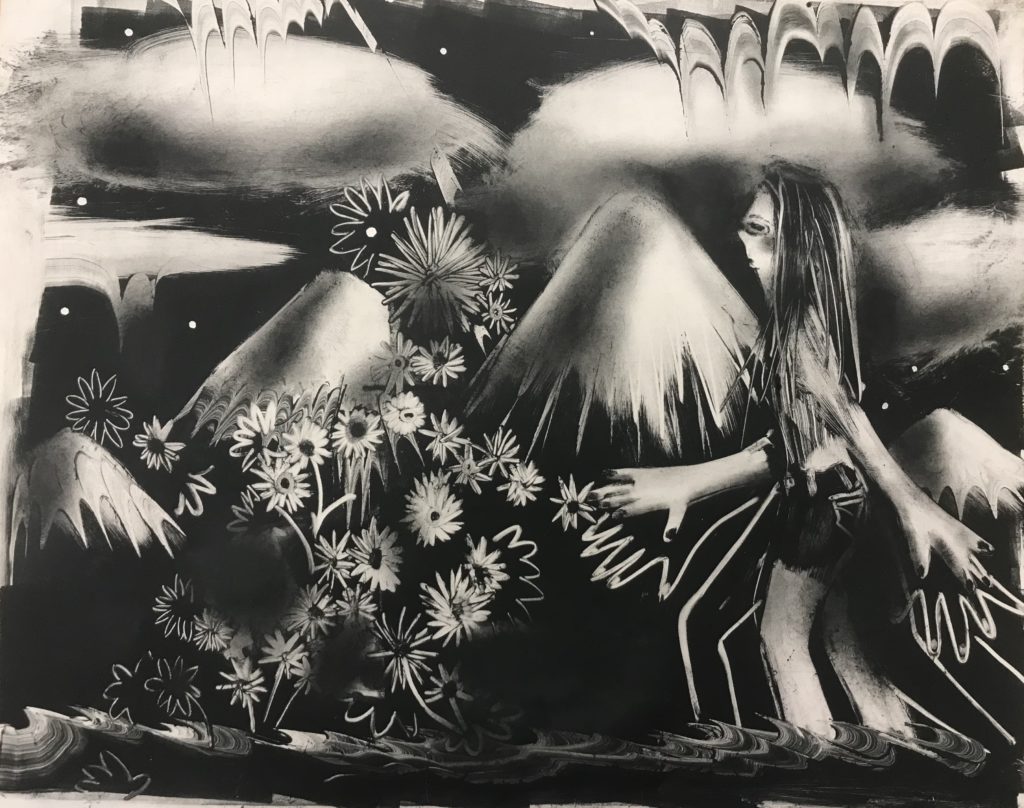

Bea Parsons, Highlands, 2020, Monotype print on arches paper.

Bea Parsons, Highlands, 2020, Monotype print on arches paper.

Canadian Art: You began making “Peyak” in the beginning of the year with a print called 2020, which you’ve said was optimistic. Do you still see it as optimistic?

BP: It really was. I was actually thinking more about vision, 20/20 vision. I like words and titles; I do take a lot of care with my titles. I feel like they actually do a lot to complete a piece. 2020 was definitely made before everything started back in January, when things were a little different. But the eyes—there are two large eyes in there, and those remained a continuous theme in “Peyak.” It wasn’t something I was emphasizing before in my work. I started really using that as a pattern and a symbol. As the year went on they became a metaphor for vision, like seeing the physical world a bit more metaphorically, stepping back and taking things in.

CA: How did the pandemic shape “Peyak”?

BP: There’s a piece called Highland that I would place as the midpoint of the year. I’m going back to my dad’s side: my dad was born in Scotland. I’ve never been there. And so in the print we have a stoner-looking figure looking a bit lost and wading through this landscape in this piece. Highland‘s obviously a pun on this kind of figure. And in front of him is a little cluster of flowers taking the shape of a human form, but they also look like flowers in a field of some sort. I wanted to kind of make a space and figure out—just as we had to space each other out in public spaces and grocery stores and lines. I kind of wanted to make a reference to that without being too didactic. That was definitely in my mind when I made it.

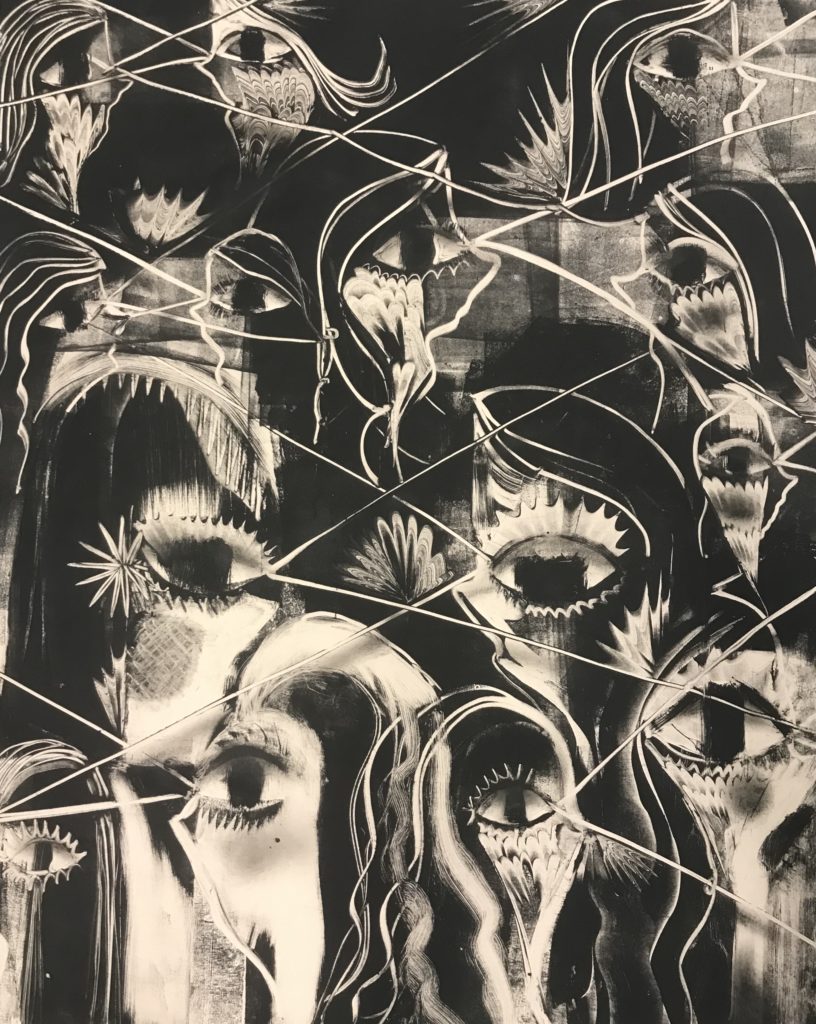

Bea Parsons, Peers, 2020, Monotype print on arches paper.

Bea Parsons, Peers, 2020, Monotype print on arches paper.

CA: You had to stop working on the series for a few months when your print studio closed due to the pandemic. Do you notice a difference in your art before and after this shutdown?

BP: I notice the later pieces I made over the summer involved a lot more groups of figures interacting with each other, gazing at each other and being connected formally with lines and patterns. I obviously wasn’t going out and hanging out with people, but maybe just the influence of missing people, and I think also just the visual aspect of looking at screens and interacting with groups of people on Zoom and whatnot, unconsciously came in or was starting to appear in the work. There’s one called Peers and there’s a very feminine side-profile figure with large eyes looking out. And there are these sightlines coming out, criss-crossing throughout the screen. I don’t try to get too literal with what these are, but that seems to be the general sense I get when I step back and look at it again.

To see more work by Bea Parsons check out her upcoming solo show at Franz Kaka in Toronto April 22 to May 22, 2021.

Bea Parsons, 2020, 2020, Monotype print on arches paper.

Bea Parsons, 2020, 2020, Monotype print on arches paper.