Indigenous art students across the country find themselves facing unique struggles with the sudden shift away from classrooms last March due to the pandemic—and with no end in sight.

Zoë Laycock, an Anishinaabe Métis, who is a fourth-year visual arts student at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, says that adapting to the online classroom for her has been an “extremely steep learning curve.”

Her practice focuses on Métis beadwork and oil painting.

Laycock says that doing hands-on tasks for online classes feels “weird” and “precarious,” but she believes that it has been a source of personal growth. Among the things she has grown is her online presence. Laycock had kept her online life very private, but recently she has developed social media profiles to showcase her artwork and potentially network with others digitally.

Zoë Laycock, Growth On The Forever Road..., 2019. Glass Czech seed beads, black lambskin leather stretched over brass hoops, 11 x 45 cm.

Zoë Laycock, Growth On The Forever Road..., 2019. Glass Czech seed beads, black lambskin leather stretched over brass hoops, 11 x 45 cm.

It has been a challenge to represent her work online and have it noticed. That’s especially true in mobile formats, Laycock explains, as it is easy for people to absentmindedly scroll past.

This has pushed Laycock to “navigate an art practice through an online lens.”

Yet one difficulty she faces in the online art world is the lack of human connection.

“You miss out on connecting with people and peers through an artificial online connection,” says Laycock.

Throughout the pandemic, she came to the realization of the importance of community.

“We kind of took for granted our ability to be connected in real life, and we have to find ways to do it online.”

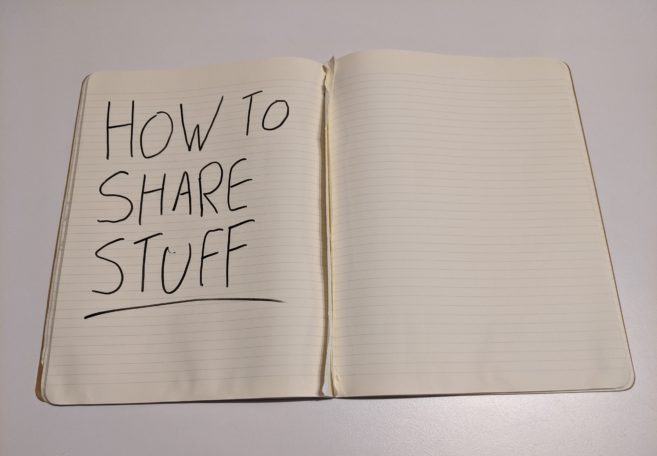

Zoë Laycock, Nookomis/Nimishoomis, 2020. Digital beading and oil on canvas, 7.62 x 10.16 cm.

Zoë Laycock, Nookomis/Nimishoomis, 2020. Digital beading and oil on canvas, 7.62 x 10.16 cm.

Laycock learned how to target specific audiences, how to build a website and, most important, how to represent her artwork in an impactful and engaging way for Indigenous People.

“I have a passion for my Indigenous community and to support youth and families,” Laycock explains. She says she wants to raise awareness about Indigenous culture through her art. “Everything I create is contemporary, with my own Indigenous perspective.”

Using a range of muted greys and browns in her paintings, Laycock attracts the eye with brightly painted Anishinaabemowin words.

“I find the use of text in art and painting really meaningful when linked with cultural preservation.”

Laycock says that she is part of a new wave of Indigenous artists celebrating their culture through art.

“I wouldn’t say I’m revitalizing because I know that a lot of our communities and cultural practices are thriving, but I am making a statement of that cultural triumph…that it exists in our current colonial world.”

She takes pride in her artwork, which is connected to her own personal, intimate experiences as an Indigenous woman navigating mainstream colonial society.

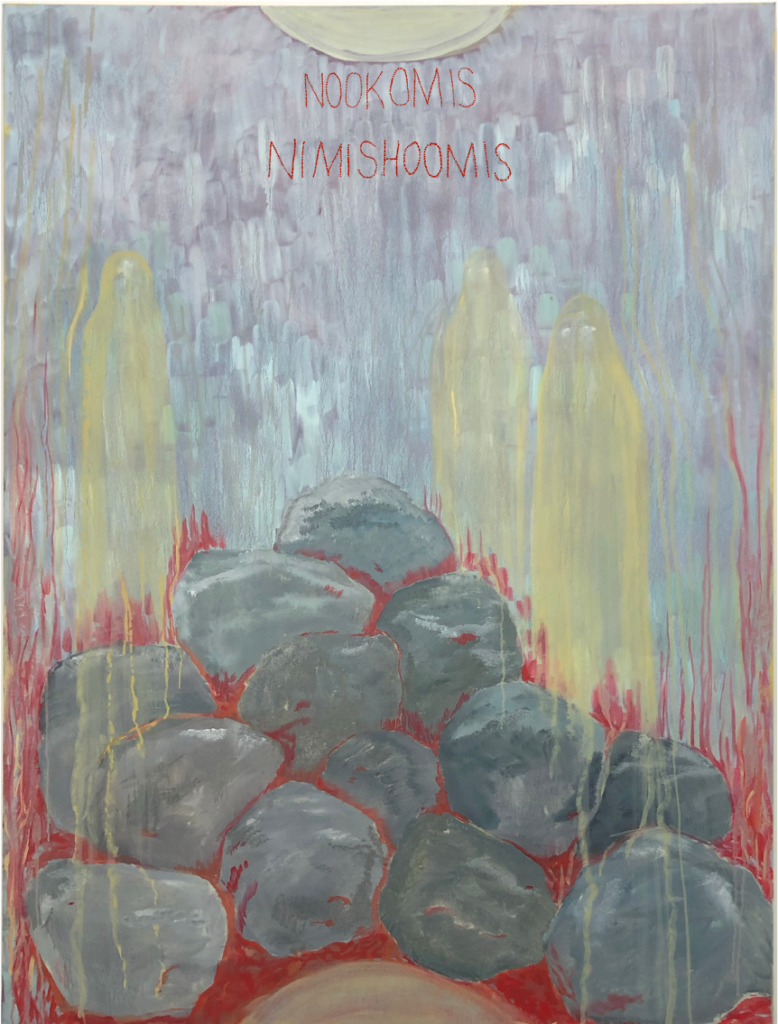

Kris Reppas, Across the Fire, 2021. Glass beads and embroidery thread on velvet shroud.

Kris Reppas, Across the Fire, 2021. Glass beads and embroidery thread on velvet shroud.

Graduation is on the horizon for many students, including Kris Reppas, a fourth-year Kanien’kehá:ka student majoring in fine arts at NSCAD University.

“I’ll admit it is a little daunting, and I can’t tell if it’s from, you know, just having to leave the nest, just not being prepared because you know we’ve lost this year due to COVID.”

Reppas is also experiencing difficulties with online learning.

“There’s definitely been a shift in the scale of the work that we’re able to produce and also a bit of the quality as well,” says Reppas.

Reppas feels the burnout of screen fatigue and is tired of virtual connection.

“It doesn’t feel like you’re really connecting with people.”

As an art student, Reppas finds it difficult to show his work and receive accurate feedback. He feels as though showing his work through screens is not really adequate for his learning needs as an art student because virtually viewing his work is not the same as viewing it in person.

Compounding these challenges, Reppas feels there is not a lot of support at NSCAD for Indigenous students. He says that there is no Elder to go to for support, nor a place to welcome all Indigenous students.

“I was using a lot of my cultural stories and trying to work on decolonization, but it didn’t make much sense when I’m using tools of colonization,” shares Reppas about his experience with printmaking.

The mass production of printmaking reminds Reppas of the process of colonization, endlessly reproducing sameness. This repetition pushed him to explore other mediums, like beadwork. He says the process of beadworking allows him to produce unique pieces based on his experiences and talent that also reflect his identity.

“I’ve been really thinking of how I can give back through my practice.”

Reppas has been selling his beadwork and donating some of the funds to the Six Nations land defenders—a group of Indigenous People and allies who are currently defending their territory in Caledonia, Ontario, against a proposed housing development known as McKenzie Meadows.

“There’s definitely been a shift in the scale of the work that we’re able to produce and also a bit of the quality as well,” shares Reppas about some of the struggles he has experienced since online learning became the new normal for students around the world.

He explains that despite the pandemic, he still notices a lot of microaggressions at his school.

“My professor emailed me to ask if I could provide resources on the history of beadwork. And at first I didn’t really think anything of it, but then I kind of took a few days and I sat there and I was like hey wait a second, why am I, as an Indigenous Person, having to educate my professors?”

Reppas explains that he feels as though other students are not expected to “cough up” the entire history of an art practice.

Kris Reppas, Across the Fire, 2021. Glass beads and embroidery thread on velvet shroud.

Kris Reppas, Across the Fire, 2021. Glass beads and embroidery thread on velvet shroud.

Currently, Reppas is collaborating with a friend, Emily Sheppard, on the exhibition, “Across the Fire.” One of the good things about online learning is that it allows Reppas to have extra time to be more flexible around his artmaking.

“We’ve been exploring death coming from both of our cultures. I’ve been looking at the Mohawk traditions around death and what our stories are.”

In preparation for the exhibition, Reppas has been sewing beadwork and tufting on soft coffins, or death shrouds, whereas his collaborator, Sheppard, is creating soft coffins from a westernized view of death. The soft coffins are a way for Reppas to learn more about his culture’s death practices.

“In my main practice, I’ve always been focused on the topics of care and labour, so it felt natural to shift into making the topic of death more accessible through the labour of beadwork.”

“Across the Fire” is on in Halifax from March 2 to 11, 2021, as part of the Anna Leonowens Gallery Window Exhibitions.

Zoë Laycock, Giizhig, 2020. Seed beads and oil on canvas, 7.62 x 7.6 cm.

Zoë Laycock, Giizhig, 2020. Seed beads and oil on canvas, 7.62 x 7.6 cm.