Marc Quinn. Yinka Shonibare. The Chapman Brothers. Ryoji Ikeda. Cory Arcangel.

These are just a few of the high-level international artists who have had their first major solo shows in Canada via the DHC/ART Foundation.

Housed in a couple of heritage buildings on rue St-Jean in Old Montreal, DHC/ART has, since its opening on October 5, 2007, done exhibitions that are at once intelligent and accessible, expansive and intimate. (All the exhibitions are free to the public, and often come with workshops, artist talks and panels.)

It all exists thanks to one person—Phoebe Greenberg, founder and director of DHC/ART.

Raised in the family that runs the massive real-estate firm Minto, Greenberg was once an experimental theatre actor who trained and toured in Europe. Now, she is not only head of the non-profit DHC/ART, but also of the nearby, for-profit PHI Centre for innovation. Greenberg has also been producer on a couple of award-winning films—including Denis Villeneuve’s Cannes-lauded short Next Floor and the Oscar-nominated Incendies.

This Wednesday evening, DHC/ART officially marks 10 years with the launch of the group exhibition “L’Offre”—a show spun off from the question “How loaded is a gift?”

Here are some other questions for Phoebe Greenberg, and her answers, on the eve of DHC’s 10th anniversary.

Q: What’s the first piece of art you remember liking?

A: I was at the Frick in New York City with my father. I must have been 8. And I was fascinated with a portrait done by Rembrandt—a self-portrait. That’s very classic considering what I do now!

Q: What was the first piece of art you collected, and why?

A: Well, in principle, I’m not a collector. [DHC/ART is not a collecting institution.]

But I did buy my first piece of art when I was living in Paris. It was by an artist named Philippe Second. I was living in a loft in Paris, and he was one of my neighbours.

Cory Arcangel, Works from the Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations series, 2009–2013. Installation view. Courtesy DHC/ART.

Cory Arcangel, Works from the Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations series, 2009–2013. Installation view. Courtesy DHC/ART.

Q: Montreal has some great public art museums. Why did you decide to start your own private art space rather than help expand the existing public museums?

A: Well, I think that my notion of how people were to interact with art was slightly different than there would be at a larger museum or gallery.

I was quite inspired by the Fondation Cartier in Paris in terms of its many dimensions, and its ability to exhibit and engage academically.

Granted, in the United States, many art foundations house the collections of the founder. But my vision was more ephemeral. I wanted a place to exchange ideas around contemporary art in a format closer to a foundation than a large museum.

So there’s a certain intimacy to what we offer. And also, because we don’t rely on public funding, there’s a certain nimbleness that is innate in some of the choices we have been able to make when presenting our exhibitions.

Q: What do you mean by “nimbleness”?

A: With Ed Atkins, for example, we were in Istanbul and curator Cheryl Sim was able to have a conversation with him. Then, he was able to visit the foundation within a couple of months, and we were able to present his show in a timely fashion. The nimbleness of our organization is due to its size.

Installation view of Ed Atkins’s Even Pricks, 2013. Courtesy the artist/Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York/Rome, © DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Installation view of Ed Atkins’s Even Pricks, 2013. Courtesy the artist/Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York/Rome, © DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Q: What do you know now that wish you had known when you started out with DHC/ART?

A: I think the foundation exists because there was room for it in Montreal, and there is a need for it academically—we do a lot of work in education.

I also believe that there is a thirst for contemporary art now—more so than 10 years ago when I first presented this idea.

Q: Can you tell me more about the way DHC/ART’s success has to do with it being in Montreal?

A: Well, I think that Montreal is a young city, and I’m delighted that so many people have embraced the foundation. We have between 12,000 and 15,000 people visit each exhibition. I think that’s largely because there’s curiosity about art, and that we’ve made it accessible, and created a certain intimacy with the art, while also contextualizing it in and academic fashion.

Q: Some of the artists DHC/ART has exhibited are known to shock, like Marc Quinn and the Chapman Brothers. Which DHC show has surprised you most and why?

A: I was quite partial to the Chapman Brothers, because I had discovered them at White Cube [in London] more than a decade ago, with their lithography.

And I went to Korea to meet with them when they opened a show in Seoul. I was able to talk to them personally there, and then Jake came to visit the foundation and they agreed to do the show. I think, because it was such a personal mission of mine, I was delighted that they said yes.

There was also Michal Rovner. I had seen her at the Venice Biennale when she represented Israel. It took 6 years for her to come to Montreal, but I was delighted to present that show; I think that her work is really important.

The ephemeral quality of the foundation enriches my life, because I get to spend half of the year with an artist, and then something else happens. It’s exciting because we also think about how best to engage with the public.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, “Come and See” (installation view), 2014. Courtesy DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, “Come and See” (installation view), 2014. Courtesy DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Q: The next exhibition, “L’Offre,” addresses the complexity of giving and receiving gifts. Why did you think that was a good fit for your 10th anniversary?

A: That was Cheryl Sim’s idea, I think in celebration of 10 years. She felt strongly that she wanted to meditate on the idea of a gift, and began to assemble that show around the notion that the foundation is a gift to the city. I was a little nervous about it – but I am delighted by the show.

Q: Why were you nervous?

A: I like the foundation to speak for itself; I’m not necessarily somebody who wants to be in the public eye. But I’m delighted we’ve been around 10 years.

Q: You are also a film producer, artist and actor. So I was wondering what your thoughts are about the Canadian government’s recent cultural policy overhaul. What do you think Canada’s cultural policy needs are right now? Which are being addressed? Which are not?

A: Well, I also run the PHI Centre. I think that looking at innovative ways that this generation consumes culture, and giving some thought about artificial intelligence, or other forms of tools that we didn’t look at a decade ago, is important.

But I’m always in support of the starving artist. The more money that we invest in ideas and innovation and art, the more it enhances our lives.

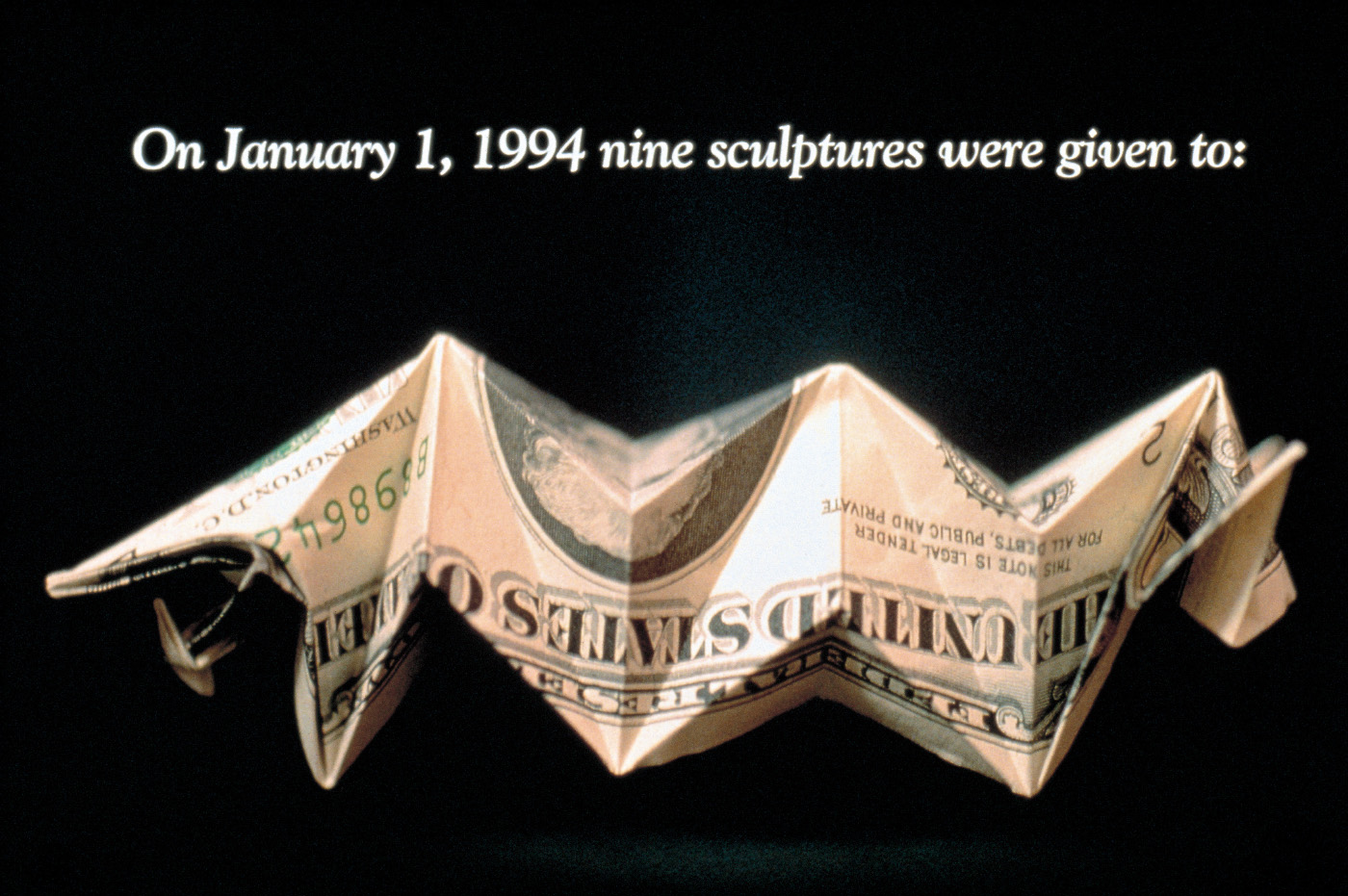

Lee Mingwei’s Money For Art #1-5 (1994) is part of the group exhibition ”L’Offre,” opening at DHC/ART on the evening of October 4, 2017. Photo: Via DHC/ART.

Lee Mingwei’s Money For Art #1-5 (1994) is part of the group exhibition ”L’Offre,” opening at DHC/ART on the evening of October 4, 2017. Photo: Via DHC/ART.

Q: Many cities in North America—Montreal perhaps excepted—are increasingly unaffordable for artists to live. And there are recurring questions about the role artists play in gentrification and the rise of property values. Given that your family runs one of the country’s largest real-estate developers, and you love art and artists, what are your thoughts?

A: I think you are right in identifying that Montreal is an easier city to live in from a real-estate perspective comparable to Toronto or New York. I lived for many years in Paris, and again, these problems arise there too.

The only comment that I have is that artists migrate. Berlin is an example of a city that lends itself to offering living opportunities to young artists. It would be somewhat comparable to Montreal. I don’t really know what else to say.

Q: What are DHC’s biggest accomplishments of the last 10 years, from your perspective? And what do you hope for in the 10 years ahead?

A: First of all, I’m delighted by the team. I have some people in the foundation who have been with me the whole ride. We’re a small team, but we’re really effective.

I hope to be around in another 10 years. I’ve met some young people who are now in their 20s who visited the foundation when they were in high school—or elementary school—which is kind of interesting.

So I think how we have found our place the city is a great accomplishment.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

A view of DHC/ART Foundation in Old Montreal. Photo: Gleb Gomberg.

A view of DHC/ART Foundation in Old Montreal. Photo: Gleb Gomberg.