There’s something hysterical about laughing into your laptop: pointing your face toward the screen, letting sound vibrate through your vocal chords and out into the speaker for an unknown audience. Laughing into your laptop, all alone in your apartment, or maybe with a friend: the gesture could be read as feminist, for it is an attempt to embody a space (the internet) that can be disembodying. In Erin Gee’s most recent artwork, the web-based Laughing Web Dot Space, internet users who have experienced sexual violence are invited to record their laughter for the site. Both practical and conceptual, Gee’s artwork becomes a space for self-identified survivors to let it out in a way that remains nameless and faceless. In the age of #MeToo, Laughing Web Dot Space is a gesture of solidarity with survivors around the world. It’s a different way of networking: more vibrational than discursive, more ephemeral than the hyper-visible acts of “outing” and disclosure taking place both IRL and online.

Gee’s work was launched as one of eight new commissions by Eastern Bloc, in an exhibition that celebrated the new media space’s ten-year anniversary in Montréal. As Amber Berson notes in her recent review of the exhibition, “All of the works on view pair invited artists with pioneering Canadian artists of their own choosing whose practices have often pushed the boundaries of technology and perception.” While the exhibition has now closed, Gee’s Net Art piece lives on. She serves as both the artist and the de facto caretaker of the website—maintaining its domain, organizing and editing the sound files, protecting it from hackers as best she can—and will continue to keep the domain active as long as she can.

In her practice, Gee experiments across music performance, choral composition, virtual reality, robotics, language and interactive art to create feminist work. I first got to know Gee from our shared time as intermedia studio students at the University of Regina in Treaty 4 lands, where she was a founding member of the audio/curatorial collective Holophon. In the years since, Gee has gone on to have a thriving practice as a new-media artist and educator working in Montréal.

I spoke with Gee over Skype about her new work, feminist energies, the cathartic potential of laughter and the internet as a kind of collective nervous system.

Lauren Fournier: You’ve never done a web-based project before, have you? I find this surprising.

Erin Gee: It’s true. As an artist I feel very web-adjacent. For years, I’ve been following artists that typically make work with internet sites and technologies, I’ve read the essays, and I even curated X+1, an evening of internet-inspired art at the Musee d’art Contemporain de Montréal with Sabrina Ratté, Tristan Stevens and Benoit Palop in 2015. These are some of my favourite artists (word up to Jennifer Chan, one of these artists I’ve been following for a while. She was also in the Eastern Bloc show!). So, it’s something I’ve been paying attention to for a long time, but this is the first time I’ve explored human voices and electronic bodies through the internet.

LF: As an artist, you have a long practice of working with the voice—whether digital voices in human bodies, or human bodies in digital voices. You’ve worked with voices speaking and singing, and multiple voices singing together as a choir, but this project marks the first time you’ve worked with voices laughing. There is something poignant about encouraging survivors to record their laughter, in contrast to recording voices that are articulating stories or specific words. What it is about this project that drove your interest in laughter?

EG: Well, in addition to the voice I’ve also been exploring the materiality of emotion, how our internal states “speak” through our bodies. Laughing combines both these interests, in how our emotions speak, how our voices reflect what is inside us. I wanted to create a space for people to be in the presence of survivors of sexual violence, but also to make sure that survivors wouldn’t have too much asked of them in that space. I’ve been thinking about how a virtual, sonic space might exist between survivors or for survivors: a space where we don’t need to share words, justify or retell horrors we already imagine too much of. Some survivors don’t like being seen as victims. Some survivors aren’t sure yet how to identify: they might be at the stage of “I know something bad happened to me but I can’t figure out what happened.” This site allows for people who have complicated feelings—as well as uncomplicated ones. [Erin laughs, a bit nervously.] Laughing is an expression of who you are, and there isn’t a need to justify that laughter: there isn’t the need to explain that laughter. The publicness and permanence of the internet today makes a performance out of the simplest text communication. One is haunted by their words, good or bad: “maybe I used the wrong word, maybe I offended someone.” The laughing interface is immediate, personal, from the gut, and a relatively low-stress option because of its anonymity and ambiguity.

LF: And folks who participate in the work are not “seen”—especially not in the ways they might be when they come out online as a “survivor” in other online spaces.

The laughing…is immediate, personal, from the gut, and a relatively low-stress option because of its anonymity and ambiguity

EG: Because of how major social media companies actively discourage anything less than interlinked identity verification and legal names online, “coming out” becomes a dramatic moment that impacts your whole social network. Survivors have nothing to be ashamed of, but not everyone wants to be a public martyr or hero, or draw attention to themselves, or even knows what to say. Laughing Web Dot Space doesn’t take any data beyond the recording. This being said, it’s still personal—your voice is very characteristic of who you are: if I heard a close friend or family member, I’d probably recognize the sound of their voice anywhere. I have been thinking about the internet’s earlier manifestations of exploring togetherness in a way where you can be anonymous, avoid doubting yourself or overthinking things.

LF: There is a freedom to being able to let something out of your body—up and out through your voice—without it taking the form of words. I suppose it could also be tears, or screaming—but you’ve chosen laughter, a significant shift away from the Sad Girls of mid-2010s internet feminist art-making, or the shouting of punk. Laughter is vibrational, guttural—leaves you feeling a little bit better afterward. And, in the absence of a specific joke, no one gets hurt.

EG: I think this is the special power of voice and sound.

LF: You describe Laughing Web Dot Space as a virtual laugh-in for survivors of sexual violence, and you specify that these can be survivors of any gender. It isn’t a women’s-only space.

EG: The issue of gender is a super complicated one, and I think we should all know by now that women are not the only people that sexual violence happens to. The #MeToo movement is seen by some to be an anti-man movement; while much violence is perpetrated by men, I wanted to centre this project on the reality that sexual violence hurts many people. All survivors have the right to space and to be heard. The technological infrastructures of social media makes voicing and healing easier for some people but harder for others. I wanted to create a different space in which people could just put their emotions and put their voice, and there wouldn’t need to be a discussion about that involvement. You’re just in the club because you’ve contributed.

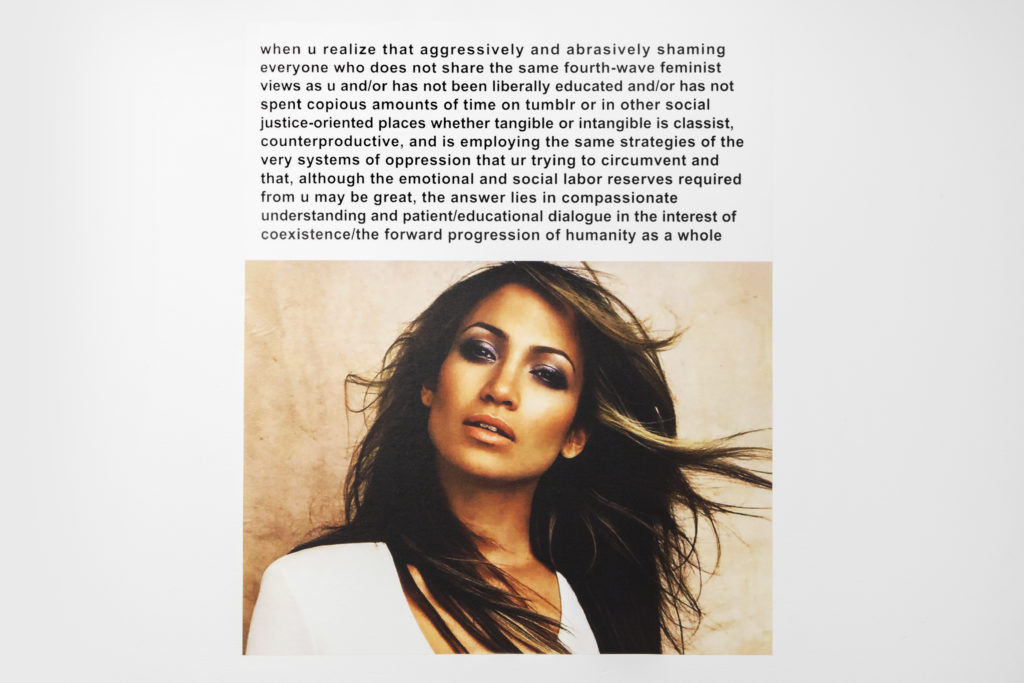

LF: It’s interesting, this capacity to create community through anonymous online networking without the baggage of language. Language is politicized, and the internet is a ripe space for folks to scrutinize each others’ language—and for language to be wielded in hateful and/or alienating ways. I think of the work of the Latinx artist @gothshakira—another Montreal-based artist working with online life in feminist ways. I think specifically of her memes, in which she names the unchecked privileges and aggressions of “woke” language policing, even as she mobilizes some of that same language through her self-described “intersectional feminist memes.” There’s ambivalence there.

@gothshakira, when you realize that aggressively and abrasively shaming..., 2016. Meme (image macro). Installation view in "What would the community think?" at Xpace, Toronto. Photo by Yuula Benivolski. Courtesy Emily Gove/Xpace.

@gothshakira, when you realize that aggressively and abrasively shaming..., 2016. Meme (image macro). Installation view in "What would the community think?" at Xpace, Toronto. Photo by Yuula Benivolski. Courtesy Emily Gove/Xpace.

And her memes are funny. They make you laugh, but the laughter comes from having that very knowledge and terminology that her memes are sending up. The irony, of course, is if you find the joke funny, you are also probably complicit. While the language of the “woke” might inadvertently marginalize those without access to, say, a liberal arts graduate school education, most folks can make the noise of laughing—or sounds that approximate laughter. I’m aware of the potential ableism in this statement, but—most people can laugh.

EG: Exactly. It’s complicated for me because, this is an artwork but it is also a very personal act of solidarity for myself with anyone who might connect with this. I wanted to create a space that could show the diversity of the people affected by sexual violence. Like you said, laughter has a low barrier of entry.

LF: Have you found it cathartic to laugh into your own artwork? When the website launched, your laugh was the only laugh on the website.

EG: Recording that laugh was easier than I thought it would be. I had anxiety about being the first voice that laughs—like I needed to have this really perfect laugh. The idea of sincerity was haunting me too: how do I get this sound art rolling and be sincere to myself? The week I did the recording was the week of the [Brett] Kavanaugh trial, and the events happening seemed so surreal. My heart was so full of emotion in general, and I felt like I just had to get something out! I don’t even know what the laughter was: the laughter was expressing: life is surreal: what is happening? The end result might be that my laughing on the recording sounds pretty bitter, but this is part of the site. There’s already a range of different kinds of laughs on there. There’s this amazing shrieking laugh, and another person who sounds like they’re having a great chuckle. There’s one that’s super silly and giggly, and another that sounds deep and like a super villain.

LF: Your point about the specific week of the Kavanaugh trial resonates with me. I know that I felt a lot of anger in my body that week, and was like, “Why do I feel all of this rage in my body? And how can I get rid of it?” More artists and theorists are starting to parse what it means to say, trauma lives in the body. How do we work through that which exists on the level of vibration? How do we politicize our nervous systems? To me, laughter is an integral part of that.

EG: Sara Ahmed is a feminist theorist who talks about the cultural politics of emotion, and she makes the argument that we live in a far more emotional than objective time. Emotion is typically gendered female, hysterical, embodied: I have been working with my art to explore emotion very seriously. But returning back to the experience of healing and survivors, physiologically laughter is, as corny as it sounds, very healing: even going through the motions of laughter will give you some benefits. For instance, studies have shown that, when people activate the muscles to smile, they get a bit of a mood boost. This relates a lot to other aspects in my practice, like the relationship between physiology, emotion, embodied experience and technology as well.

LF: It’s like laughter yoga.

EG: What’s laughter yoga?

LF: You don’t know?! It’s when you’re in a room with a group of people, like in a yoga class, and you make yourself laugh: the idea is that this put-on laughter becomes real laughter, and there are supposed health benefits to that. I’ve never done it, but I’ve been curious.

EG: Yeah, and when I think about the difference between a laugh-in, where people are all together in a physical space for a specific duration of time, I like to think of the website as a virtual monument, in a way. Even just listening—that is a form of participation, that can be counted (as visitors to the website). Even though it’s lacking in physical presence between survivors, it’s something that will be there, and something that people can count on: a website is always open, and as long as I register the domain and don’t get hacked, it will always be there.

Erin Gee, LaughingWeb Dot Space, 2018. Web-based work.

LF: Is there a way for you to know where the laughs are coming from, in terms of across the country or around the world?

EG: I haven’t signed up for an analytics service. A part of me was really interested in that, thinking like, “Oh, we could put pins on a map!” And then I thought, any level of me actively tracking who the contributors are—I want to get away from that.

LF: So your website becomes an alternative kind of space on the internet—a space where your location isn’t tracked: a place where you don’t need a face, a name, a story.

EG: It’s kind of a throwback to the 1990s.

LF: Yes! There’s something very 1990s-feeling about how you’ve designed the website. I mean that in the best way. Is the democratic nature of “all survivors can just laugh into this thing” tied to the democratizing of the 1990s World Wide Web?

EG: In the ’90s we had web counters, you know, kind of dorky things like: “Thanks for visiting my website, 50 people have visited.” [Erin laughs.] In the 1990s anonymity was really embraced as part of the internet. There was this idea that you could have an alternate life on the internet and create personas. And there was a comfort in being an avatar, in being a different kind of yourself with strangers. This is less and less common with internet 2.0, or the social web, where your Google profile and your Facebook account are interlinked, verified gateways to your real, legal self. In some ways this builds trust among users and normalizes the internet, but it’s done for very neoliberal, monetary reasons—everything personal is monetized on today’s internet, in an economy that conflates attention with profit. I think of how confusing it must be for young people with Instagram accounts who are just having fun, but that fun turns into followers and likes that turn into money. The confusion between the life that is public and the life that is just for yourself can be very confusing to navigate. In the 1990s, there were different anxieties.

LF: As millennials, so often we turn to the internet for answers; at least I do, in spite of myself. And it rarely gives me what I need. I think of other digital artists, like Trudy Erin Elmore, who creates otherworldly, hyper-digital landscapes where post-human bodies are affixed to their laptops and smart phones—our ways “in” to the internet, almost in a religious way. During a studio visit, Elmore described the internet as “our collective nervous system.” We pour our emotions into this thing that is the internet—we pour into it our sadness, frustration, desire, despair. I’m wary of making generalizations about people’s experiences of the internet, but is it fair to say that we spend a lot of time on the internet and it doesn’t really make us feel good? And that there’s something about having a space on the internet where you can be in your body in a different way, or be encouraged to interact with the internet in a different way?

EG: Yeah, I mean I don’t know if folks are laughing in relation to other laughers they hear on the website, or if they’re going deep within and like, coming out with their primordial laugh! I like to imagine a space where everyone can feel together in the laughter, but the trick of online artwork, especially anonymous work, is that you rarely have the privilege of seeing a reaction from the public.

LF: In a way, your website becomes a receptacle to take in the excess energies that survivors of sexual violence might possess in their bodies. You’re holding space for that, as a net.artist.

EG: Holding space is something I was very interested in while building the work. Despite all the gendered assumptions of technology, my experience is always that technology instructs the designer and maker in actions of caretaking and maintenance. Websites are fragile things: code depreciates, and the website needs to be cared for. Every day I use a command to check the database for audio submissions: each submission is a gift. With the recorded sound files, I perform light edits to remove mouse clicks and integrate it into the master track on the website. I’m learning a lot about cyber security in this process as well: when you create feminist space on the internet, you have to be a lover and a fighter! Laughs. I have good backups, I’m ready.

LF: What comes next for you, in your practice?

EG: I’m really interested in physiology and autonomous behaviours of the body. In the past, I might have connected this to autonomous, cyborgian bodies. But what I’m most interested in is the complexity of the human body—how it’s already so complex, and technical, and amazing. I’m still exploring my fascination with vocalization and technology (within digital arts practice), but what I’m trying to do is not necessarily highlight the technology, but to use technology to highlight the human, as a very complex and fascinating system. For instance, I’m really interested in the link between machine automation and ASMR. I’m deep into it. I’m still invested in finding strategies for illuminating the autonomous and mercurial material of emotional experience via biodata. I hope that the real laughter in this virtual website might bring about some physical healing for some people, like an emotional hack.