Vancouver-based multimedia artist Ho Tam practices in multiple disciplines including video, print media, photography and painting. Tam was born in Hong Kong and then educated in Canada and the US. He worked in advertising companies and community psychiatric facilities before turning to art. Through his work, he reflects on Asian experiences of the past and the present in North America and beyond, usually in a humorous and satirical manner. Early on, he received recognition for The Yellow Pages (1993), his first artist’s book, which confronted Western stereotypes of Asian cultures and spoke to a subjectivity rooted in Asian Canadian sensibilities. These days, he spends most of his time publishing, which he considers as “a one-man show.” Indeed, he plays various roles: as creator, editor, printer and publicity agent. He is so efficient that he is able to publish new work every few months. While tirelessly undertaking print projects, he is also frequently seen at international art book fairs.

Tam also shows his publications in the format of a gallery presentation: transcribed from paper to wall. Last month, he opened a retrospective of his publishing works, mingled with some of his earlier paintings, titled “Cover to Cover” at the Richmond Art Gallery. Two weeks ago, he opened the solo exhibition “A Brief History of Me” at Paul Petro Contemporary Art in Toronto. Later this year, he will be participating in art book fairs in Shanghai, New York and Seoul.

Tam runs hotam press, a publisher of artists’ books that play with pun and humour that relate to the artist’s own lived experience. Besides working on his own artistic projects, Tam has also initiated several collaborative publications with Canadian and international artists. Frontline, published in Beijing, China, includes Chinese-translated interviews with 18 Canadian photo-based artists who discuss their practice. Through the 88Books and XXXzines series, he works with artists to distribute their books internationally.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon, I sat down to chat with Tam in Toronto. In this interview, Tam talks about some of his most notable works and how he has managed to balance his artistic practice and self-publishing endeavours since the 1990s.

Henry Heng Lu: You have a very diverse and versatile practice. You make videos, draw, photograph and, more recently, you publish. How would you describe your work?

Ho Tam: You pretty much described everything I’ve done. I don’t know how to categorize myself. Recently, I see myself more as a publisher. Art-wise, I have worked with various mediums. What I haven’t done is sculpture, but in my recent show in Richmond there are a few sculptural elements. I think it’s very exciting for me to be trying different things. It is a kind of comforting prize for me, for not being too successful—like I don’t have a certain market or customers to cater to, so I can do whatever I want at any time.

L: In terms of subject-matter, Asian masculinity seems to have manifested in your overall practice, and it is discussed also from the perspective of a queer Asian man …

T: For Chinese Canadian artists, painting seemed to be the default artistic medium to employ. When I first started making art, I was painting. And people would ask me why oil painting. And that’s when I was thinking more about of myself. Asian, male, and queer…they are all part of me. This was very prominent in my work. I was not satisfied with just painting, so I went beyond that and started to make work with other mediums, such as video, print and collage, about myself and wherever I was living. These days, I guess I don’t necessarily deliberately prioritize all these identities in my work but since they are all part of me, it just comes out naturally. There is no getting away from that.

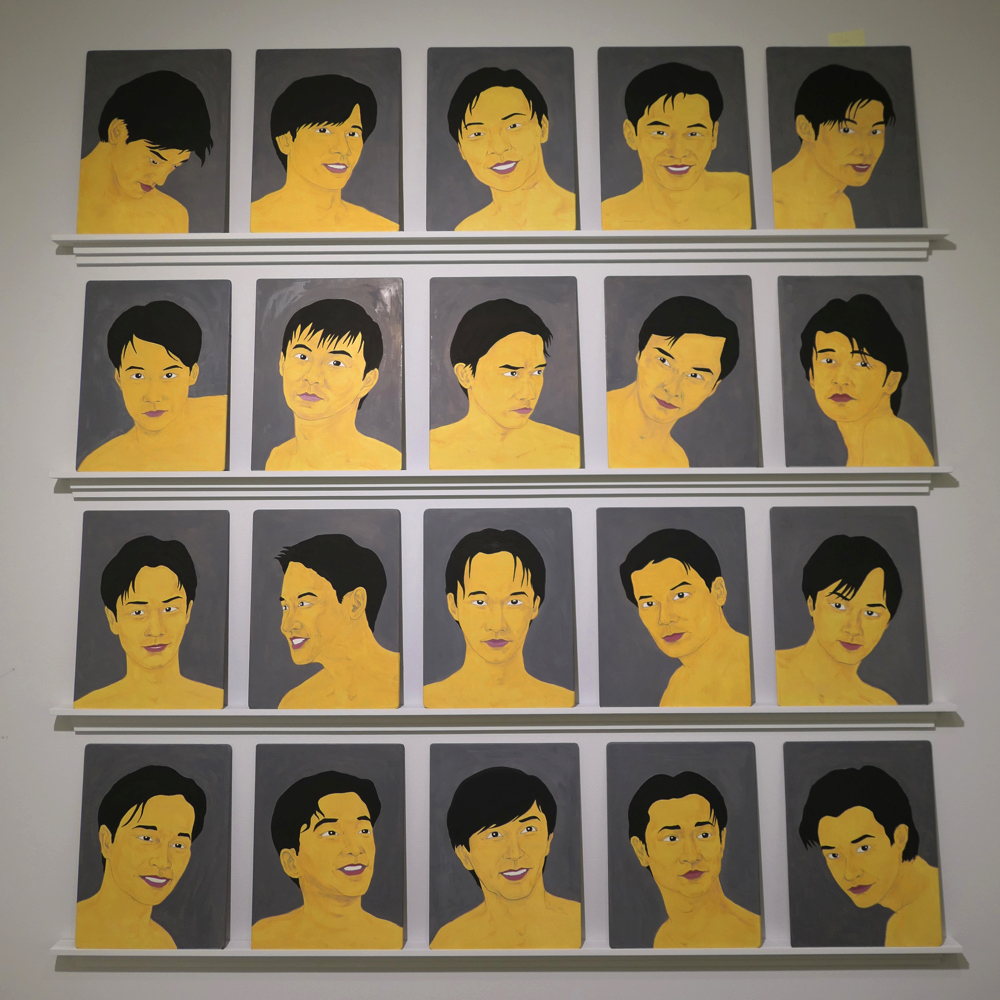

I started to explore Asian masculinity in my early career, for example, in Matinee Idols (1994) and The Salary Men (1995–2014). I was trying to challenge the conventional ways Asian men are seen in North America mostly. It was almost a satire, but at the same time I was trying to present an alternative to how Asian men are seen.

L: Gay Asians are often exoticized and fetishized in the Western context—how do you position yourself in the predominately white queer culture? Is there a particular image of gay Asian men that you want to present through your work?

T: Some of my earlier works speak to the struggles of being a queer Asian person. The series Icons (1993–94), for instance, explores that with stereotypical imageries of Kung Fu and Lucky Fish Sauce. There is a certain racialized sexual fantasy associated with the gay Asian community. With my work, I consider myself as a provocateur than an educator to diversify images of Asian men.

L: Your more recent focus is on publishing. You’ve published a lot of your own artist’s books through hotam press, and you also run 88Books, which offers opportunities for photographers from mainland China to get their work printed. Can you tell me a bit about these two presses?

T: In 1993, I made my first book called The Yellow Pages. Since then, on and off, I have wanted to make books once in a while, and I made a few between then and around 2010. The idea of getting into publishing was not something new for me, but at the same time it actually came out of a project that I worked on with Canadian artists. I did an interview book with some photo-based artists (Frontline). It was published in China. That started my interest in making more publications. I realized working with commercial or mainstream publishers might be a bit limiting, so I started 88Books to work with artists from mainland China.

I was working on Frontline when I was in China. That’s when I ended up meeting a lot of Chinese artists and photographers. I realized there were only a handful of them who could get their work out of China, so I wanted to bring the work of those who couldn’t to international scenes. Then I dreamed up having an independent self-publishing house that would distribute works on the internet and internationally. And it was somewhat successful, I think; I am quite pleased that I have made 88Books.

L: You mentioned 88Books received wide media coverage. In light of that, I’m interested in the notion of what “Chinese” means; it’s a complicated term to categorize multiple populations. As China has taken on a bigger role in the world, do you find your work influenced by mainland China’s cultural specificities and/or politics? For example, in the latest edition of The Yellow Pages (2016), there are images of skin product advertisements and movie posters that are not in the previous editions of the project.

T: To me, my work is always about our time. And being of Chinese descent, I try to speak about my own identity, background, or say history in my work. And therefore, I look into some of the environments or the world that we live in to find sources of subject matters. I guess that’s how the whitening skin products featured in the 2016 The Yellow Pages. I have always kept an eye on things circulating in the mass media, especially those about political situations in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, and I think about how they affect me as a Chinese Canadian, and us here in Canada. And then I sort of make comments on them in my work.

It’s definitely an interest of mine. China is a big country with a long history. It is a rich resource that I can refer to in my practice.

L: I have found that some of the older practices of Asian Canadian art address Asian Canadian sensibilities very specifically. For instance, there are more works about being Chinese in Canada rather than about contemporary China.

T: I guess I am perhaps more invested in that side than some other artists of my generation.

L: How do you manage your self-publishing practice financially?

T: Basically, I am not really funded by anybody. I got a grant two years ago. Because I’d been publishing for a while, so I started to feel a bit confident to apply. But generally, it is very hard. Each project of mine is different. I don’t know what to write in the applications, so self-publishing has to be sustainable for me. I do a lot of work myself, from design to even the printing sometimes. I also produce them on demand, which helps save a lot of money. I make 10 to 20 copies each time. It’s easier in that sense, instead of spending a big chunk of money. And that helps me make many projects.

And then I also have odd jobs to help sustain me. I used to have temporary jobs. For a while, I used my own savings on 88Books. But now, after not having other jobs for many years, I am basically running my business very frugally.

L: Very recently, through hotam press, you published the latest edition of your ongoing multilingual publication project titled The Greatest Stories Ever Told. This new edition features three versions of the Chinese language that share the same roots: Simplified Chinese, Cantonese and Traditional Chinese.

T: I wrote the stories in The Greatest Stories Ever Told and then paired them with collages of images from international banknotes. The stories are modern-day fairy tales as well as satires. A lot of them comment on the world and try to find ways to rebalance power. The project started with an English edition, followed by a French one. And then I was like, why stop there? So far there are 12 editions of different languages. The Chinese one has 3 versions of the language. I was initially interested in translating it into Cantonese because it is my mother tongue. There is a movement among Cantonese speakers who are trying to preserve the language—a dying language. And then I thought of other expressions of the Chinese language like Simplified Chinese and Traditional Chinese. That’s how I got this book of three versions of Chinese expressions now, addressing the complexity of the idea of translation. Translations should never be singular.

L: Can you share your insights into the differences between working as an artist in the 1990s and now, in terms of working environments?

T: I am more into my own work. Publishing is very different from the visual arts scene that I was involved in, back in the day. Now, I just shut my door, do my printing and distribute my work online. Occasionally I go to art book fairs to sell the work. So I don’t deal with the art or gallery scene as much. But I think social media definitely has changed the ways artists show their works and promote themselves.

L: Do you have any advice or suggestions for younger practitioners in publishing?

T: This may sound kind of cliché, but you just have to do what you want to do. Let the other things take care of themselves. You need to have a vision.

Henry Heng Lu is a Toronto-based artist and curator. He is co-founder and curator of Call Again, an initiative committed to creating space for contemporary diasporic artistic practices and to expanding the notion of Asian art in the context of North America and beyond.