Some things Kandis Williams says to me within the first five minutes we meet:

“Progressive civil rights is unlanguaged and unseen, however widely it’s spoken of and imaged.”

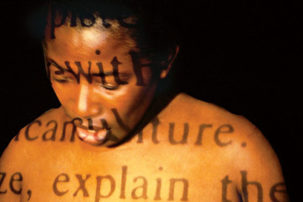

“Every image retrieves and obsolesces something, obscures the means of its own production…”

Using her background in dramaturgy, Williams makes performance with collaborators, working with dancers to create what she calls “social choreographies of dissonance.” During her 10-year absence from the United States, she lived and worked in Berlin, where she developed her early collage practice and immersed herself in theory and philosophy while bartending to support a studio practice.

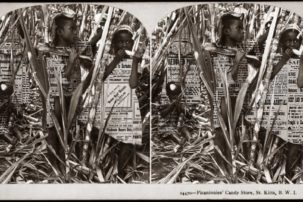

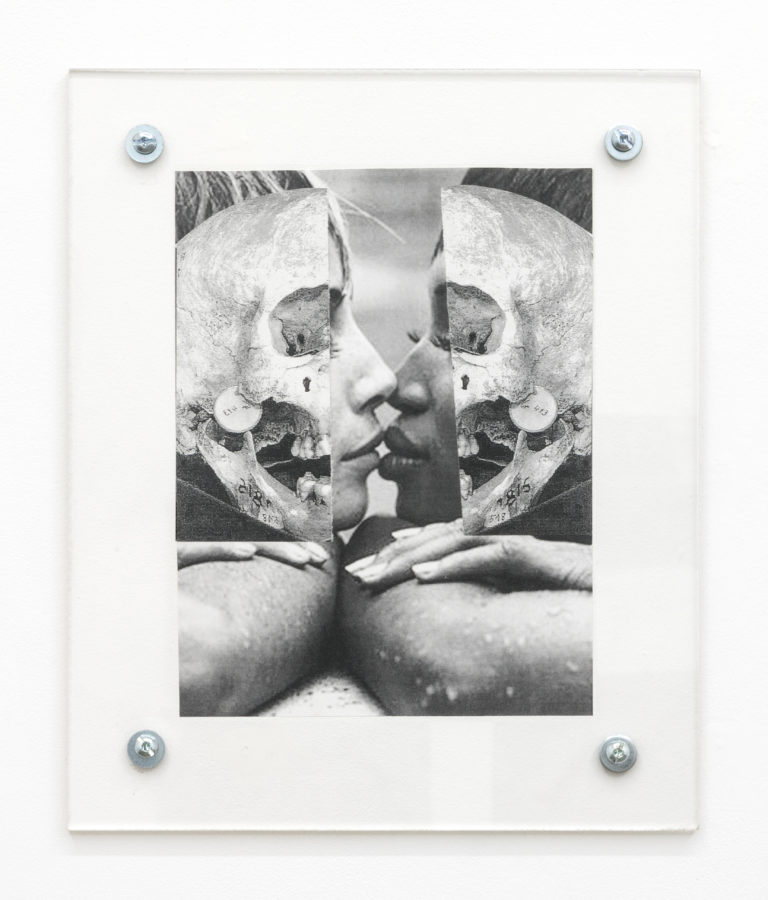

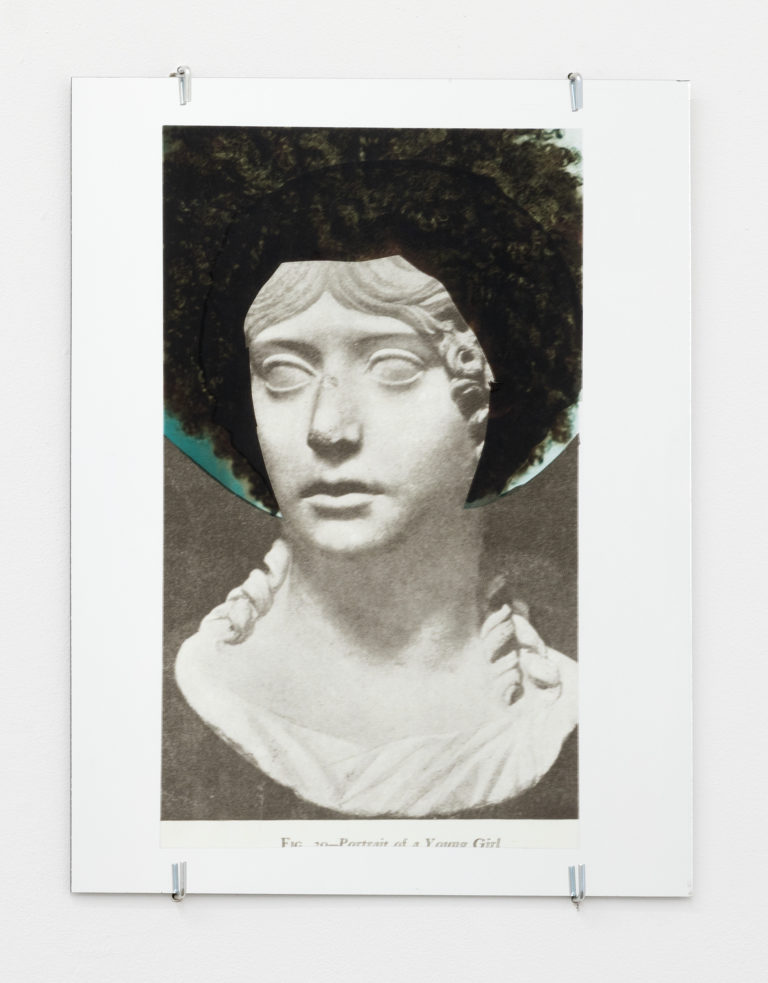

At Cooper Cole in Toronto, I look at the work in Williams’s current solo exhibition, “the rivers of styxx,” with her comment in mind: “The surface of the image obscures the means by which it’s made and the materials from which it’s made.” Her montages are made from printed transparencies held between plexiglass or mirrored glass. In The Bathers of Acheron two models—a Black woman and a white woman, Naomi Campbell and Christy Turlington—kiss. Their profiled faces are partially overlaid with skulls, revealing a kind of performative sexuality, an intimacy, and an underlying sentiment of terror and death and obsolescence. In Rheme: Coffin and Crowds, an image of a group of enslaved people in chains is overlaid onto a set of classical stone figures.

When we meet we’re both exhausted. It’s the end of the day, and we fold our long brown bodies on the couch in the Cooper Cole office. Our formal interview devolves into an hour-long conversation that jumps on and off the record, about the realities, challenges and excitements of being a Black person in the art world at this particular moment in time. In the following edited and condensed interview, Williams talks about the politics of image-making, Black community in and out of the art world, distrusting gestures of inclusion and the challenges of Black collaboration within white art space.

Yaniya Lee: You gave a talk titled “Reproduction is not a metaphor” at Emily Carr recently.

Kandis Williams: [Yes] I’ve been thinking about the tensions between individual self-expression and different means of capturing that self-expression [by the] art industry. As we achieve economic agency we also regress or liquidate political propositions of separatism and radicality.

I’m thinking about what it is to come from such extreme rape culture as a Black woman, and its implications within our everyday interpersonal interactions, and our larger political aims, especially in the art world where we have so many unlanguaged connections to the images of empire. [Those images are] the forms and fragments of Platonic ideals that now serve as our perceptual tools.

YL: So you’re taking a wider perspective of the art world system as a whole, and Black creators within it.

KW: Black civil rights strategies for progress, from silent protests to Buy black campaigns, are obsolesced every generation because our structures stay inherently white supremacist.

I’m thinking a lot about how progressive civil rights is unlanguaged and unseen, and radical, especially right now. [When] extreme gestures of Black separation and solidarity are forefronted they erase a Black politic of hybridity, they erase a lot of the interraciality that’s inherent. This is really explicit in the art world because we make images.

I’m thinking about a tiered system that appraises or validates certain works, you know, and certain content, and then ultimately sort of liquidates the position of that author, while it takes the author away from community in really intense capitalistic ways.

YL: How do you feel?

KW: I know this since I went to art school: I left my community.

YL: How did you leave your community?

KW: I left my community in Baltimore to go to art school in New York.

The way you have to rationalize your intention as an artist [in art spaces] is very different than in Black vernacular. I’m really aware of not having my own natural voice, [that] I don’t operate daily in my natural voice; my natural voice may be too communicative. Hyper communicative…

Leaving that community, you don’t identify other people like you right away who had made that same bridge. [Leaving] creates this kind of shame. I think Black kids in art school worry about “How do I talk to my mom about these things? I sound different now.” I hear a lot of young Black and marginal artists making pictures and making work around being able to communicate with their community, and trying to bring their community into art space, or bring art space into their communities. I feel like that’s a fraught position. [It’s] caused by the fracturing of the psyche [that happens] when you enter an art system that’s inherently white supremacist.

YL: We’re being trained to want to succeed in those spaces, but priority is not given to the kind of art that you would want to bring back to your community.

KW: It’s also the fact that that art happens canonically—it’s not that white people own ideas, or that white space owns art. That’s not the thing; the thing is that we have to navigate white supremacist structures that have created the values in the spaces [in which] we want to exist, that we want to be archived in, that we want to be remembered in.

Of course every museum that’s being accused of being white supremacist is gonna throw the youngest Black artist they have out there: put him on the walls [or] put him in the space for the night. [But] they’re not collecting us. They’re not looking at the numbers of their permanent collections and reworking them. They’re not saying their boards have to be representative of the communities they serve.

These spaces that sort of sloppily include and sloppily curate many Black voices for the night will put all Black [people] together. That’s a liquidation of our individuality. We’re the only people who see our difference in those situations. In those spaces, we’re the only ones who see the nuance in each others’ practices.

Saidiya Hartman talks about the burden of individual freedom. Within image culture, I still see systems of capture that are extremely hierarchical and extremely competitive, and that put young Black voices in competition with each other, and that are constantly obsolescing older Black voices.

I feel I’m not a part of a lot of the conversation online with other Black makers in terms of community because I’m not into critiquing other Black practices. I don’t even really look at other artists—for my work I look at writers and I look at philosophers.

Kandis Williams, The Bathers of Acheron, 2018. Paper, collage and plexiglass. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.

Kandis Williams, The Bathers of Acheron, 2018. Paper, collage and plexiglass. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.

Kandis Williams, Styxx, 2018. Sticker on mirror glass. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.

Kandis Williams, Styxx, 2018. Sticker on mirror glass. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.

YL: Why aren’t you into critiquing?

KW: I’m not into critiquing right now because I feel like basking in the flood of new Black voices and all of their friction. Even if I don’t participate in direct dialogue, it’s nice to not be alone. I see [that dialogue] matrixially complicating popular political assumptions for everyone, and I’m here for it.

If, for every exhibition that was supposed to be politically inclusive, the first image you saw was a picture of that institution’s board, that’s the conversation I want to be a part of.

YL: That’s the hardest information to find. They don’t count how many white people there are, they count only the people of colour, and even then it’s infrequent.

Black people—Black artists—are popular right now, and the question for many is, “How do I survive after this moment?”

KW: Exactly. It’s a huge question for a young Black artist, and it’s a huge question for me. A lot of young Black artists are brought into art spaces together and being curated together and they’re calling that community and that doesn’t, for me, do enough of the explanation of the difference between Black culture and the culture of American representation. The American art world, for me, is not a space where Black community can exist, or should exist or has existed.

YL: And it’s not safe for us to be having those very complicated conversations about colourism and about how we interact with one another and about how power plays in proximity to whiteness. It’s hard to do that in a sphere that is dominated by whiteness.

KW: It is very unsafe.

YL: And how do we protect each other? They are hard conversations that we have to have with one another. And they are difficult; it’s not all good. People are doing weird things that we have to talk about, but how can we have those conversations when we’re constantly hustling, trying to survive?

KW: This language of abstraction that we’re building within discourse and building within these spaces often becomes a technology that other people use to express their suffering—so, like, we create this technology, this metaphorical language. We survive because that’s what we are prepared, at an unreasonable cost, to do. The aesthetics of survival, overcoming, co-existing, the common sense of pushing forward together and rebuilding and repairing ad nauseum are the realm and dominion of Black image–production.

YL: An aesthetics.

KW: Yeah, an aesthetics of always pushing, always moving, always figuring shit out, and when other people adopt that language they erase the politicality, or the means for political enfranchisement, for Black bodies. We invent the project of emancipation only to be excluded from the representation of its progress.

YL: Do you think there is revolutionary potential to art, or that art can be a form of activism?

KW: I think artists can be activists, I don’t think art can be.

YL: Why art, then, for you?

KW: Because I’m an artist. And I don’t think that white people own art, or the art industry. They don’t. I think it’s an issue, again, of an interior architecture. And language. If we retrace these steps back through the metaphor of Blackness to get to the value—like, I love Black Lives Matters’ ideology, whatever I think of their actual organization: no life will matter until Black lives matter. That is really important philosophical groundwork for a lot of work. I can look at Adrian Piper, I can look at Sylvia Wynter. I can look at all these amazing philosophers and that’s how I’ve read Western philosophy. That’s the loophole that I read, as a Black woman, through Hegel, through Kant, through Freud, through fucking Foucault, through Lyotard, through Deleuze, through all these people. We’re that hole, you know what I mean.

YL: And nothing happens till that happens. If we can’t change that fundamental thing, of understanding humanity and who is human—I don’t know, none of it matters.

Kandis Williams, Shallow pool of Bacchanal Freedom, 2018. Printed plastic and plexiglass. 32 x 48 In. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.

Kandis Williams, Shallow pool of Bacchanal Freedom, 2018. Printed plastic and plexiglass. 32 x 48 In. Courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery.