A few weeks ago I got a phone call from my friend Alyssa Bistonath, asking me if she could come and take my portrait through the window. A Toronto-based photographer and filmmaker, Bistonath had started working on a series documenting her friends during this period of physical distancing and self-isolation. She is not alone in this. Since the end of the first week of lockdowns in mid-March, photographers across the country have suddenly joined photographers worldwide in making isolation portraits. Shot on porches, in doorways and through windows, these photographs are proving to be extremely popular, and they join images of face masks and empty public spaces as the dominant visual language of the coronavirus pandemic.

But the doorstep portrait is not new. As Didier Aubert notes in a 2009 Visual Studies article, traditionally such images have unambiguous things to say about access, intrusion and the white, liberal, middle-class gaze—all issues which are deeply embedded in the documentary approach. Though Aubert was mostly writing about projects that sought to document poverty and rural life, these current isolation portraits traffic in the same transformation of private family life into a constructed public performance for a larger audience. The dynamics differ though: in these threshold quarantine spaces, we see not people asserting agency by restricting access to some other intimate visual truth of their lives, but people seeking momentary respite from the overwhelming reconstitution of time and space that makes up life under pandemic conditions. Access has been otherwise revoked, and intrusion appears quite welcome.

When Alyssa called me, she seemed to be in pursuit of something different, given that she was not documenting strangers as a business or community service, but rather walking across the city to photograph close friends. What follows is a conversation about her engagement with this process and what it means to cope, photographically, with life during COVID-19.

Alyssa Bistonath. April 2: Hiba, my collaborator and my twin. We talked about what it means to have conviction (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Michèle Pearson Clarke: This project has been spurred by the sudden reality of having to physically distance ourselves from each other, and go into self-isolation. What were your initial thoughts on that experience?

Alyssa Bistonath: It’s been unreal to witness how slow we were as a country to accept social distancing, even though we saw the virus spreading exponentially around the world. It’s not that we don’t have the capacity to understand that there are people out there who are sick and dying, but I think the denial—that it could happen to us and our loved ones—is a way of coping. I mean, we’ve never experienced the whole world going through the stages of grief at the same time.

What kicked in for me was in line with the hostile-environment training I did when I worked as a photographer in international development. There, we learned that in a bad situation, verifiable data leads to early acceptance. Early acceptance means that you can act quickly and decisively, and help the people around you. And this can be true in a sudden crisis or a long-term one. That first week of social distancing, I was filled with adrenaline. I knew I needed my camera as an outlet for all of that energy, so, on March 18, I walked out my door and to my friend’s house and took her portrait through her window.

MPC: Why the turn to portraiture?

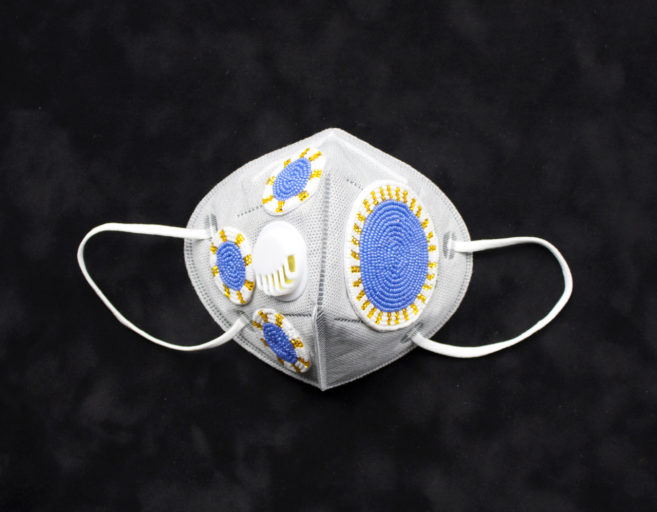

AB: Everything is coloured by this pandemic, everything has new meaning and everything is interrogated in a different way. I’m seeing and capturing empty streets, discarded gloves and masks, and business closures like everyone else. I really feel it’s important to document how our landscape is changing during this time. But for me, the essential element is capturing intimate portraits of my friends while maintaining the distance necessary to keep us safe. I’ve been photographing many of these people for over a decade—capturing the everyday and major events in their lives. In a way, they are my constant in this very surreal time. And barriers often help me define a project. In this case, the rules of social distancing act as a framework. This is an essay of how we were together during the pandemic, even though we couldn’t do any of the things we normally would.

I’ve also been thinking about the ways in which showing people that they’re coping may in turn help them cope better. We can be happy and afraid at the same time; no one needs to be either all of the time (especially in a crisis). Showing them their sadness or anxiety can also provide a reference, and perhaps they will have more empathy for others and themselves.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 18: The Burkes. Melissa is my emergency contact. We chatted about social distancing, and the stress of having parents living in other cities (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 18: The Burkes. Melissa is my emergency contact. We chatted about social distancing, and the stress of having parents living in other cities (2020). Courtesy the artist.

MPC: You used the word intimate to describe these portraits, and the intimacy is readily apparent in many of these images, especially compared to others I have looked at where photographers are documenting people they don’t know. Can you talk about this difference, and what this means for your project?

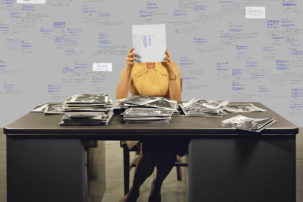

AB: That’s a good question. Let me think about that for a second. I mean, there are a lot of photographers shooting portraits through windows right now, and I think we’re all trying to keep our cameras up, if that makes sense. But people shoot through windows and in doorways and on porches all the time. I remember photographing the band Glissandro 70 in the window of Rotate This back in 2005 or ’06 for Eye Weekly. I guess what I’m asking myself now, what I’m always asking myself, is what are the power dynamics in photography in relation to the vulnerabilities people are holding close at this moment? People feel really trapped right now. Being the person taking the photograph, especially in documentary photography, is a power position. When I’m shooting commercially, sometimes I’m photographing someone I met 30 seconds prior. There isn’t the familiarity that you have with someone you’ve lived alongside for years. I can only do my best to represent anyone in an authentic way, but sometimes it’s a guess.

With the loved ones who are pictured in these photos, I have known them for so long that the power isn’t necessarily with me. I’ve lived with them, we’ve worked together. I babysit their kids. They take care of me when I’m sick. I’m the person they put down as a passport reference. They even brought me toilet paper when I couldn’t get any during the hoarding! I’ve spent the 10,000 hours multiple times over with them—I’m an expert in them, and vice versa. There is a mutual tenderness that I want to capture. I’m not looking for anything that they are not already giving. We are already vulnerable to each other.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 19: MPC, my friend, collaborator, and the first practicing Caribbean artist I ever met. We talk a lot about grief and sometimes we talk about tennis (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 19: MPC, my friend, collaborator, and the first practicing Caribbean artist I ever met. We talk a lot about grief and sometimes we talk about tennis (2020). Courtesy the artist.

MPC: What role do your other photographs, the ones of streets or signs or refuse, play in this series?

AB: Amateur and student photographers shoot a lot of stuff like graffiti, signs and the like because the camera is helping them see everything anew. I also see it in travel photos. People are somewhere foreign and suddenly a label on a bottle is photo-worthy because it’s new to them. And that’s how it is right now: everything is recontextualized. I’m a tourist in my own neighbourhood. Now, bubblegum on the ground is more offensive. I don’t normally see medical gloves and masks discarded everywhere. The street signs in a way are helping me orient myself, because things feel chaotic. I laugh when I see that people have “curbed” items, like books on finance, or whatever. Like, yes, I could probably use that book right now, all things considered, but I am definitely not touching it during a pandemic.

I have a fear that this newness will be normalized or forgotten post-pandemic, and we won’t remember how unreal this was. So, in a sense I am collecting evidence that validates what my memory might later overwrite.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 21: Dar, my soulmate. This was a particularly rough day for her—she was in a fog of anxiety, but needed clean clothes. She works in the arts and has since been placed on emergency leave (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 21: Dar, my soulmate. This was a particularly rough day for her—she was in a fog of anxiety, but needed clean clothes. She works in the arts and has since been placed on emergency leave (2020). Courtesy the artist.

MPC: The act of walking to each friend’s house to make their portrait seems particularly significant to this process for you.

AB: Last year I experienced big grief after two members of my family passed away. Walking was the only way I could deal with it. I would walk the city streets for hours every day for months. It was like I was looking for them, or looking for answers, but really I was using that time to process and accept what had happened.

Right now, leaving home feels risky, but I know that I need exercise, companionship and novelty to remain physically and mentally healthy. I leave my house a couple times a week at 5 p.m. and walk toward a friend. There is something very profound about walking for an hour to see a friend’s face, and then having to turn right back around to go home. Everything I encounter on my way to and from is framed not just by the quarantine, but also by the fact that it’s what I saw before and after a moment of genuine gladness, of relief, of solidarity. This isn’t a transaction; I need to see them. For some, I’m the first friend they have seen “in person” in a long time. Their smiles are huge.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 21: Elle and Tam, my dear friends with whom I walk often, home from Italy and under quarantine. Ironically, they were able to come home via London because it is no longer part of the European Union (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 21: Elle and Tam, my dear friends with whom I walk often, home from Italy and under quarantine. Ironically, they were able to come home via London because it is no longer part of the European Union (2020). Courtesy the artist.

MPC: Can you speak a bit about how these photographs connect to the rest of your practice as an artist?

AB: A lot of my work is about longing. I’m fixated on the concept of home, what it looks like and whom it looks like. Maybe it will always be a fascination for me. When I was making my project Hometowns, I was travelling internationally a lot as a photographer and I was honestly looking for belonging everywhere I went. I was constantly homesick for one place or another, one person or another. So, in that series, I was placing a portrait of a best friend next to a portrait of someone I didn’t know well, next to a deeply familiar landscape, next to a barely familiar one. I coloured everything with nostalgia and it felt coherent and satisfying, tolerable even. This was before Instagram, before everyone was curating nostalgic grids of their lives. People talk about Instagram as a place of aspirations, but I think people are longing for coherence. I know I’m not alone in that desire to make sense of the world in that way. I think Pilgrimages revisits the idea of contrasting the familiar with the unfamiliar.

Another project, Why We Fight, was about retroactively creating an archive for the Guyanese diaspora, because we have so little in terms of visual history. Colonialism has displaced my ancestors for more than 180 years. North America is the third continent for us, and a lot of the timeline has been lost. So the archive, and how it holds time in one way or another, just gets me. And then Portals was about placing cultural muscle memory into the archive using a science fiction framework. This whole pandemic feels like science fiction, because science fiction is about displacement. Displacement—whether it is from one planet to another, one continent to another, from one family to another—is thick with loss and isolation. Quarantine, isolation—maybe it’s corny to say that even though we’re all at home, we’ve all been displaced from our own lives. And we’re talking about that feeling more openly, and I guess I have something to say about it. It’s better than letting the denial creep back in.

Alyssa Bistonath. April 1: Andrew the singer in my old band, peeps in my front window on his way to deliver fruits and vegetables to Peter (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. April 1: Andrew the singer in my old band, peeps in my front window on his way to deliver fruits and vegetables to Peter (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 29: The Mani’s. Emily has been my best friend for over 20 years. After I left to get groceries, the kids ran 100 laps of their backyard. Schools shut down on March 13 (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 29: The Mani’s. Emily has been my best friend for over 20 years. After I left to get groceries, the kids ran 100 laps of their backyard. Schools shut down on March 13 (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 18: Hazel, an artist and my frequent collaborator is deemed an essential worker. She tested negative for Covid-19 on April 3 (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Alyssa Bistonath. March 18: Hazel, an artist and my frequent collaborator is deemed an essential worker. She tested negative for Covid-19 on April 3 (2020). Courtesy the artist.