Over the past 10 years, the Canadian auction market has changed and grown considerably, and Vancouver-based auction house Heffel has been a big part of those changes. Since the inception of its auction business in 1995, Heffel claims to have run the top 10 grossing auctions of Canadian art of all time. In 2002, it expanded into Toronto and in 2005, it opened a gallery in Montreal. Now, with its auctions of Canadian post-war and contemporary art and of fine Canadian art kicking off our national fall auction season tomorrow, president David Heffel—who runs the company with his brother, vice-president Robert Heffel—talks to Leah Sandals about auction ethics, the Artist’s Resale Right, boosting business online and more.

Leah Sandals: How have you managed to maintain a leading auction position as a homegrown Canadian operation competing against international market leaders like Sotheby’s?

David Heffel: We have a lot of significant assets that have built a great foundation for us. That started with the history that my father built when he founded Heffel Gallery. But more importantly today, having three galleries—in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal—strategically located in strong retail areas is part of that.

As well, we have over 25 team members who have reached significant stages of maturity; we’ve been conscious, particularly over the last 10 years, to really invest in our team. They’ve done a great job, with people here in our Toronto office and our Montreal office playing quite a significant role in our business. So it’s not just Robert and I that our competitors have to compete with—it’s a whole team of 25 people.

LS: In the art scene and otherwise, there can often be tensions in Canada between east and west. How do you deal with that factor in your business?

DH: You know, there are uniquenesses to the collector bases in each of the three cities where we have our previews. It’s rewarding for us in all three because we make contact with the majority of those collectors every six months. To a certain extent, a lot of those visitors have become friends. There are slightly different demographics in terms of their collections, what they collect and which artists they get most excited about.

LS: What do you see those differences being in terms of collecting in different cities?

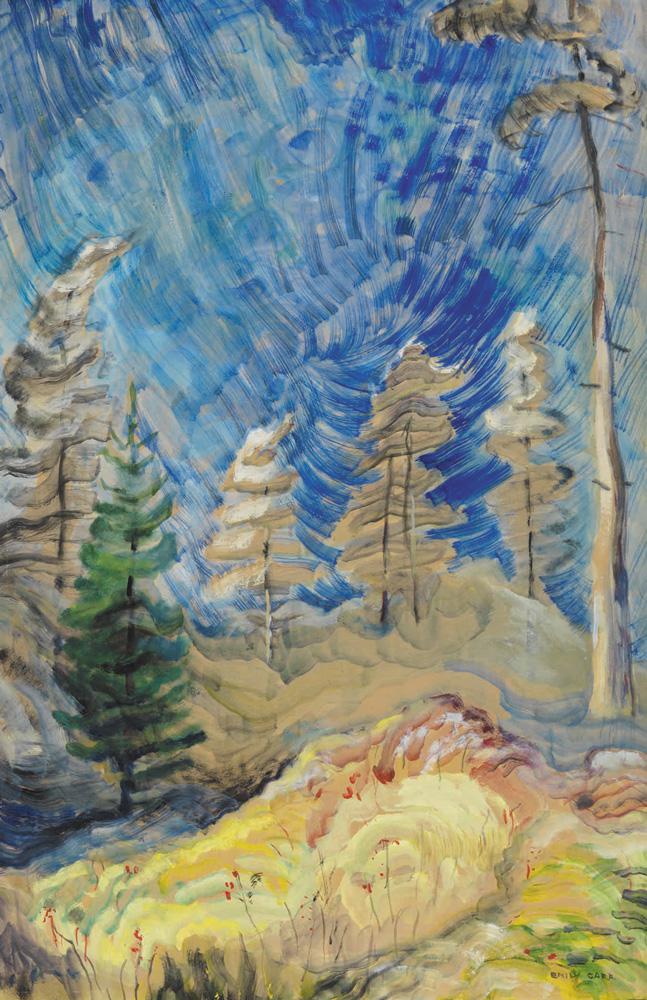

DH: Emily Carr, E.J. Hughes, Jack Shadbolt and Gordon Smith have a pretty significant following in Vancouver, but do have national interest.

Here in Toronto, the Painters Eleven, Tom Thomson, and the Group of Seven are a focus. They have national followings as well, but the epicentre of their public representation, by way of the Art Gallery of Ontario and McMichael and the National Gallery, really resides in Ontario.

And in Quebec, there’s definitely an emphasis on the Quebec painters: Jean Paul Lemieux, Riopelle, Borduas and the Automatistes. But once again, those artists still have national followings—there’s great Riopelles and Lemieuxs in Vancouver just as there’s great E.J. Hugheses and Emily Carrs in Montreal.

LS: How difficult was it to decide to expand into Toronto ten years ago, given that your company has such a strong history and base in Vancouver?

DH: You know, all of our expansions and corporate developments and strategies seem pretty obvious to us at the time that they happen. And the timing also seemed to coincide with good financial growth of our firm and the maturity of Robert and I.

The expansion and use of technology and the Internet was a massive tool that we really took advantage of early on as well, and to much greater extremes than our competitors did and still do so today.

We were the first to put our catalogue online in Canada; we were the first to conduct online auctions in Canada. We also do something Sotheby’s has attempted but hasn’t been able to do much yet in Canada—broadcast sales live on the Internet.

We also get a lot of positive feedback on the virtual tours of our previews; we do these panoramic tours which you can find on our website of the Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal previews. Often if people, for whatever reason, can’t make it to the preview, they really enjoy those virtual previews because it gives them a sense of perspective and framing that they don’t get with the catalogue.

LS: I want to ask you more about online auctions in a little bit. But just one more question about your historic base: How did Heffel begin?

DH: Well, my dad was in the steel business. He was a co-founder of Great West Steel, and was also a collector starting in the late 60s and 70s. So Robert and I were very fortunate to grow up with some fantastic paintings—paintings by Emily Carr and Lawren Harris and other members of the Group of Seven.

My dad retired quite early out of Great West Steel while still in his 40s. He dabbled in ranching, but then turned his hobby, which was collecting paintings, into his vocation. In 1978, he founded the art gallery in Vancouver. He died young, at 52, in 1987. And that’s when Robert and I took over the gallery business. We didn’t branch into the auction business until 1995.

LS: So how old were you when you took over the gallery?

DH: 24.

LS: And your brother?

DH: 22.

LS: That’s quite young. There must have been some big learning curves, to say the least.

DH: There were tremendous learning curves. But there was also sort of a fearless, youthful enthusiasm that allowed us to be, I think, quite creative in what we tried to do—without worrying too much about not succeeding. And I think it has been very beneficial for us in the long run.

LS: Thanks for speaking to that. I want to ask you next about Artist Resale Right in Canada and the difficulties it’s faced in being adopted here. CARFAC has continued to campaign to have the Artist Resale Right added to the Canadian Copyright Act, but it has not been successful yet. If it was adopted, it would certainly benefit some of the artists in your auction, like Takao Tanabe, Christopher Pratt and Gordon Smith, giving them 5 per cent of their auction sales. Why do you think it has been such a struggle for an Artist Resale Right to be adopted in Canada, when it has been adopted in some 60 other countries?

DH: Well it’s a pretty fragile market here for a lot of contemporary artists who haven’t sold significantly in the secondary market. We’re participating in the analysis of the Artist Resale Right and at this point we’re still gathering our thoughts.

I think there have been some difficulties in other markets when an Artist Resale Right has been put into place; it can be perceived more as a tax than as a benefit. I’m all for supporting artists, through whatever means and matters possible. I just don’t know if the structure of what’s been proposed is mature enough to be the right approach. It’s complicated.

Also, I think if it is implemented, it would be unfortunate if it’s just targeted on auction houses as opposed to other, more private-dealing aspects of the art world. In some regions, I believe it has been implemented through that manner, which I think is a little bit unfair.

LS: You’ve got a number of Kureleks in your auction this year; what impact did the big recent Kurelek survey that toured public galleries in Winnipeg, Hamilton and Victoria have on this?

DH: Historically, touring retrospectives and the publications that go with them have always been a great impetus to market stimulation.

We saw that when Emily Carr had her retrospective, as well as prior to that when she was paired with Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keefe in an exhibition that toured throughout Canada, the US and Mexico.

The exposure and the marketing associated with those public exhibitions definitely has residual benefits to the marketplace. And I think that’s been a contributing factor to some great paintings by Kurelek coming to market.

LS: There was also Emily Carr at Documenta this year, which I’m not sure would affect her market that much?

DH: No… but we mentioned it! It’s like building a building; each little brick adds something. The fact that Carr was not only featured in Documenta, but is now also slated for a major show at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2014 following the success that they had with Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven, is part of that.

LS: And how did the Dulwich show affect the Group of Seven at auction?

DH: You know, I think it can only be positive. It’s hard to come up with really specific marketing analysis. But we found paintings by the members of the Group of Seven in the UK that ultimately came to be offered through our firm as a result of that exhibition.

So [museum shows] don’t just stimulate collector interest from an acquisition standpoint; they also help people rediscover the importance of a family heirloom that often puts them on a road to considering selling that item.

LS: Speaking of the Group of Seven, one of the lots at your auction this week is A.Y. Jackson’s Radium Mine—one of those works that has a kind of crazy story attached to it in that it is a painting of the Northwest Territories mine where the uranium was produced for the world’s first atomic bomb. What is most effective in selling art—the story attached to it, or the actual piece?

DH: Well, how a painting gets onto a private collector’s living room wall is an interesting voyage.

But I think it starts with the early discovery. Often when a collector walks into one of our previews, we’ll look at their face when they’re coming in. Facial expressions can tell a lot; I think there is an instant sort of love affair that certain people have, or a connection with a painting.

And then, beyond that the initial discovery, the road map will be enhanced by added provenance on the work, or, you know, historical significance, if there’s a narrative or a geographical location behind a work.

Prior ownership, exhibition history, how well the work is documented in various publications—that doesn’t necessarily trigger the passion or the desire to acquire that object, but it can have an impact on the price that’s paid for a work or the value that’s assigned to it.

Lawren Harris’s Hurdy Gurdy, which we have for this week’s auctions, is an interesting example. That painting has so much going for it—ever since our staff’s first exposure to the work, everybody has just loved it.

But part of the story behind it is that Lawren Harris gave it to his only daughter, Peggy Knox. The painting has been in existence for almost 100 years, and it became Peggy Knox’s most prized possession.

At one time, she told me a story of how her dad came to borrow it back for an exhibition. There was a history of him borrowing paintings from her and then not returning them, so she said, “No dad, you’re not taking this, you gave this to me.” She told me it was her most dearest painting and she would never part with it. So no matter what financial attribution you made towards that work in the 70s or the 80s, it was unattainable by a collector.

This week, it’s being sold by Peggy’s two children, grandchildren of Lawren Harris, and it’s the first time ever that anyone privately could dream about hanging that painting on their wall.

LS: So that’s a powerful story.

DH: It’s a fact.

LS: Yes, it’s a factual story as well, which is good! Speaking of such matters, I notice the word “transparent” is in your mission statement and marketing materials. Yet Canadian authors like economist Don Thompson and sociologist/critic Sarah Thornton have noted—and expressed a great deal of concern about—the degree of theatricality and obfuscation in the art-auction business. This can take the form of things like chandelier bids, where the auctioneer raises false bids to create the appearance of greater demand. When and why are such practices appropriate?

DH: That’s a good question.

When we say “transparency,” what is transparent is the wealth of information that can be seen both by the buyer and the seller of the painting. Ultimately, the most important aspect of that is the vendor of the work knows exactly what that painting is being acquired for by the new buyer, and vice versa. As well, the fees involved—the buyer’s premium and so forth—are transparent. There is also follow-up documentation and publication of prices realized and so forth to act as an ongoing record of those transactions.

In addition to that, we don’t practice chandelier bids. I mean, there’s a pretty fine etiquette when we are on the podium. Often we’ll say, “Bid is with us.” Where the bid is should always be well understood by our bidders in the audience—if it’s in the audience or if it’s against us. In our terms and conditions of business, we make statements that we’ll bid up to the reserve on behalf of the consignor or up to one increment below the reserve.

One thing that is not disclosed is what those reserve prices are. And that’s a confidentiality issue that we maintain with our consignors, in addition to not disclosing their names.

We do try to make it as transparent and as clearly understood as possible, and we’re more than happy to answer whatever questions collectors have. We’ve spent a lot of time on our terms and conditions of business, as well as our published code of ethics, to really outline in as much detail as possible the methods by which we operate our business, which are pretty consistent with Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

LS: What makes the decision to put something in an online auction rather than a live auction?

DH: Often that decision is made by the consignor.

There can be different aspects of that decision-making process. Value is one of them when it comes to Canadian works.

But we also develop specialty sales. Sometimes we do one-artist auctions or international sales such as pop-art graphics. So the curatorial building of that auction can often dictate the difference between a work going into the live or the online auction.

Sometimes people are in a bit of a hurry; we do monthly web sales, as opposed to our live auctions, which are restricted to Canadian art, for the most part, in May or November. Though we have done live international sales—we had an Irish sale at one point, and we have also done jewellery and photography.

So we don’t have specific parameters of what we will or will not do online and elsewhere. We are always in a state of transition so we’ve also, in addition to live and online auctions, begun doing selling exhibitions, which are a bit of a merger of private sale business and auction preview. For them, guest curators come in and build private-sale exhibitions that would be previewed as an auction would and use the marketing associated with an auction, but the works would be sold privately in the gallery. We constantly want to be innovative in our business; with selling exhibition we’re not the inventors, as we’re following suit after Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips de Pury’s abroad, but we’re bringing the concept to Canada.

LS: You and your team were rightfully proud about your Lemieux sale last November that set a new record for a contemporary work of Canadian art sold at auction. So I was wondering how you felt when the Jeff Wall sale at New York’s Christie’s auction in May broke that quite handily.

DH: We’re happy to see Jeff Wall’s success. You know, we need more of it in Canada. When you hear about the billion dollars of contemporary art that was sold in New York during the auctions last week, with a very small component of it being Canadian, it’s clear we’ve got a long way to go.

LS: So when will it be time for that to happen in Canada? When will big-name contemporary Canadian artists actually have their works sold at auction in Canada?

DH: Well, we’re working on it! You know, when Edward Munch’s The Scream sold for $119 million in May, I went onto the web and compared the GDP and population of Norway to that of Canada. We’re much bigger and stronger, and our Canadian record is less than 5 per cent of that—so there’s a lot of room for improvement. The growth of the international historical market is huge. And the photo-based conceptualists like Jeff Wall and Ian Wallace and Rodney Graham—it’s fantastic to see their success abroad. Hopefully ten years from now, we’ll be moving up on that ladder. It’s hard not to get impatient!

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This article was corrected on November 22, 2012. The original copy incorrectly stated that the recent William Kurelek survey travelled to Halifax rather than Hamilton.