Over the past month, Detroit has filed for bankruptcy, Calgary has dealt with a massive flood and Toronto has again debated its ailing transit system. Such civic difficulties come to mind when considering “Draft Urbanism,” the big exhibition of this year’s Biennial of the Americas, located in Denver, Colorado. Opened last week and executive-curated by Berlin-based Canadian Carson Chan, “Draft Urbanism” is installed completely in public spaces and includes works by several Canadian artists. In this interview, Chan tells us about demanding vs. decorative public art, revamped bus-shelter beer ads, and why, indeed, we may all now be Detroit.

Leah Sandals: You are based in Berlin and are currently working in Denver. What is your connection to Canada?

Carson Chan: I was born in Hong Kong in 1980 and my family immigrated to Toronto in 1984. I grew up in Toronto and went to high school at Upper Canada College—actually the same place one of the biennial’s artists, Michael Snow, attended as well!

LS: Yes, there are a number of Canadians in this biennial. Besides Snow, works by Douglas Coupland, Jeremy Shaw, Jon Rafman, Erdem Tasdelen, Jen Osborne and Kate Sansom are included. Why did you choose these artists, among others?

CC: The biennial is about urbanism, so all the artists were chosen because I and the other curators—Paul Andersen, Gaspar Libedinsky and Cortney Stell—felt their work had something to offer regarding urban conditions.

The work that Michael Snow made is on a public LED screen. It’s a video of a clock—it reads “7:46” and slowly changes to “7:47.” So it participates both as a video and a public clock that is wrong. It’s one of several works that make us conscious of urban signage and the visual economies they produce.

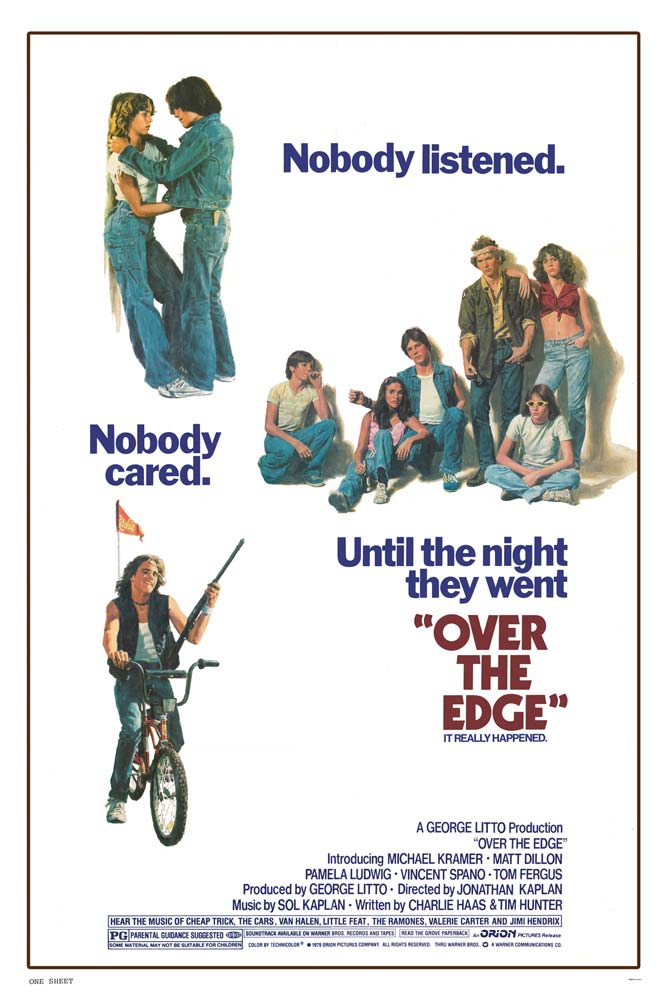

Jeremy Shaw is presenting a version of a type of project he did originally for the Vancouver Olympics—reproducing the film poster for Over the Edge, a 1979 movie about troubled youth and school shootings, and posting those reproductions around the city.

Douglas Coupland made a billboard that says “Welcome to Detroit / The world is now Detroit.” It’s a timely commentary on how interconnected cities are—American cities particularly—and asks how and whether Detroit’s current economic situation affects Denver.

LS: All the works in this biennial are installed in public spaces. In the catalogue, you say that by transforming the city itself into an exhibition, you hope to transform viewers’ perceptions of a familiar place. It’s an optimistic and utopian goal. Yet the works in the show—at least the Canadian ones—have a dark, dystopian edge. Beyond the works you mentioned, for example, Erdem Tasdelen’s piece references the current violence in his former home of Turkey. How do you resolve this tension between hope and doom?

CC: I wouldn’t say that these works are dark, so much as really tackling key issues. I think there’s a perception that art—particularly large public art projects—are meant to be “happy” and “decorative.”

What we want to show with this exhibition in Denver is that art can participate in these really difficult conversations, perhaps even opening up these conversations in a way other media cannot.

LS: Some of the artists you’ve chosen, like Snow and Coupland, have worked in the sphere of public art before. Others have not. What are the potential pitfalls of commissioning public art from someone who’s only used to making protected, white-cube-presented works?

CC: I wouldn’t say that just because artists have worked only in studios and galleries, they aren’t capable of working in public space.

Erdem Tasdelen’s work is a good example. The uprising in Turkey came out of a contestation about urban space—a park was going to be turned into a mall, and that dispute erupted into a larger revolt. He is addressing that in a billboard in Denver filled with adverbs related to the situation in Turkey. So I think the artists in this show are quite able to adapt to site-specific conditions.

Kate Sansom’s work is about our desire to escape, and it draws upon ad imagery—beer-ad imagery as well, which is important because beer is a big industry in Denver. The endpoint of urbanism for her is something anti-urban: an ad without any words on it that shows a beach, a beer, a pair of legs. We are presenting this at a bus shelter that usually houses ads, so the work is really about understanding the social dynamics of its particular site.

LS: You’ve written that “the process of urbanism is always in a state of becoming; the city we see today is but a draft of a future version.” What do you think is most vital now in terms of revising the “draft” for Denver and other cities?

CC: That’s probably not answerable. What we have done with “Draft Urbanism” is to focus on specific kinds of urban conditions as opposed to “the urban condition at large.”

For instance, there is a proliferation of surface parking lots in Denver. In the 1970s, there was an urban renewal movement that destroyed a lot of older buildings with the thought that they would be replaced by new ones, but a lot of that never happened—a lot of them became parking lots. Alex Schweder’s Hotel Rehearsal installation responded to this condition.

LS: You studied architecture rather than art, and I’m guessing this influences your approach in Denver—dealing with public spaces rather than private ones. What do you see as the main differences and commonalities between the architecture world and the art world?

CC: I think for large-scale exhibitions like biennials, the art world and architecture world are very much merging. Toronto architect An Te Liu participates in the art world quite a bit. I think these distinctions are fast becoming obsolete.

LS: What’s next for you? And when are you going to do a show in Canada?

CC: My focus is architectural exhibition-making, so the next big project is a three-day conference this fall at Yale about that. And I would love to do something in Canada—you should invite me to do something there!