Dagmar Atladóttir, Phantom Lamp from UGLY MRCL Collection, 2016. Stoneware and glaze. UGLY MRCL Collection is a series of objects that draw inspiration from the genre of horror, both in folklore and in pop culture.

I’m on an Instagram message thread called “potheads ????✨???? ”. It was started by Simon Cole, who runs his gallery during the day, but also takes regular ceramics classes from a local clay artist. The message thread is essentially a bunch of ceramics-obsessed art lovers who share images, videos and personal pottery faves. Several weeks ago, I contributed work by artist Dagmar Atladóttir.

Dagmar’s work always makes me think differently about what exactly it is that pottery is, or should do. I met her over the summer at a residency in the mountains of Western Canada. For most of the five weeks we were there, the skies were filled with smoke from nearby forest fires. Everybody handled the steady reminder of the messed-up state of the world in their own way. Dagmar, I remember, was ever cool, calm and unfazed.

Dagmar is from Iceland, originally settled by Viking explorers in the eighth century. The Norse paganism they brought with them is still a lively part of the culture, and the influence of these traditions can be seen in Dagmar’s otherworldly creations. The Sandberg Institute Dirty Art Department graduate has developed a practice that includes elements of paganism, world-building, goddess-worship and explorations of “performative sculpture.”

Halloween seems like the perfect occasion to talk to Dagmar about her work, and her cultural origins.

Yaniya Lee: Halloween is huge in Canada. Iceland doesn’t have the same tradition, does it?

Dagmar Atladóttir: No, Halloween is quite new in Iceland, but we have so many grimy old pagan traditions that we still celebrate. They’re called blót, or midwinter festival, which refers to these pagan celebrations, and also means swearing in Icelandic. After Christmas and Easter, blót is probably the [biggest holiday]. In February, every small town in Iceland does blót by holding these little celebrations, like parties. They’re very gnarly, people share ancient delicacies, which, because we had so little back in the day, utilize everything from the animal. We eat the testicles of the sheep and we eat rotten shark and this all has to do with paganism.

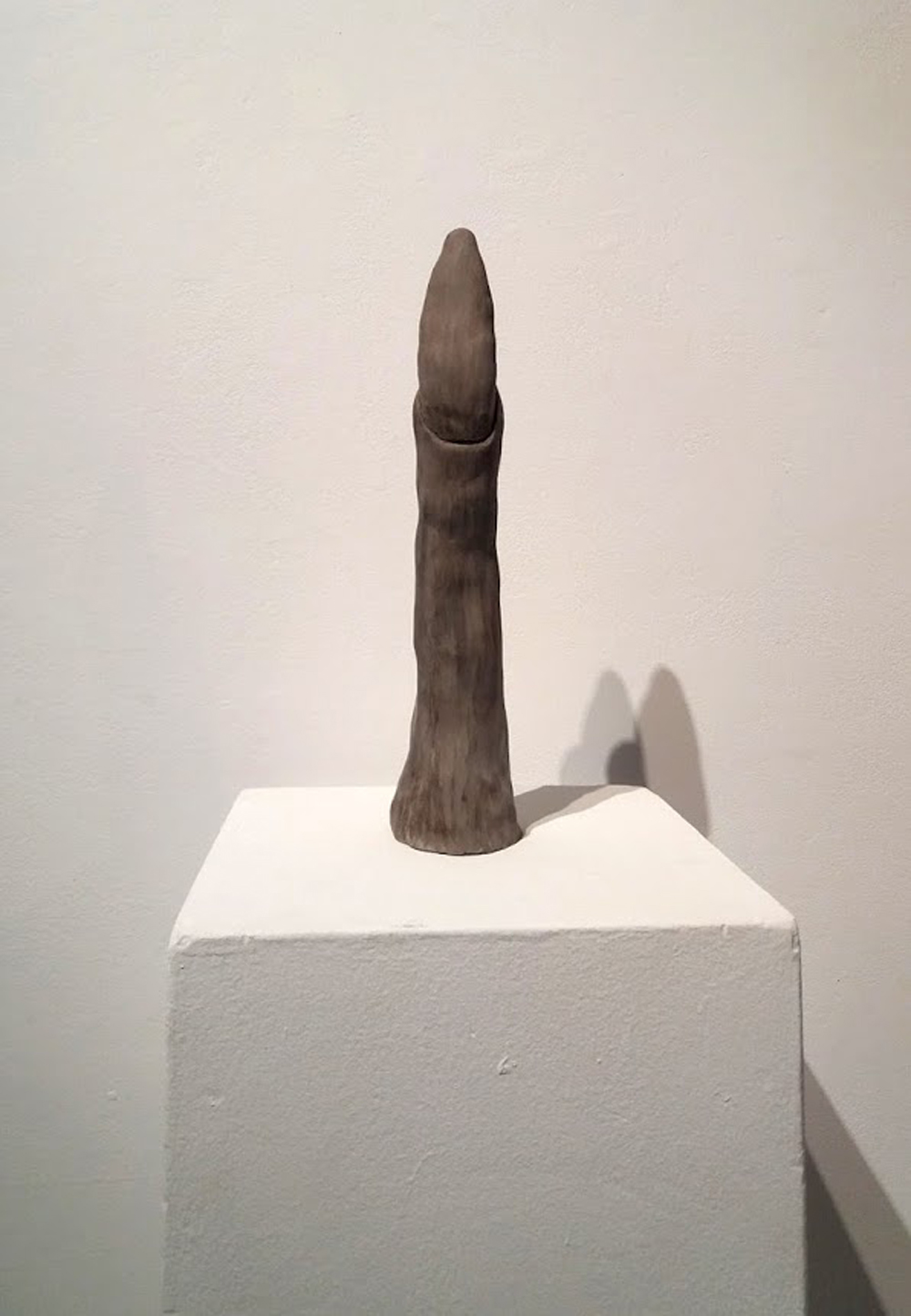

Dagmar Atladóttir, God Nail, 2017. Black clay, 60 cm. A hypothesis of a tool, used in pagan times for witchcraft in Icelandic Sagas.

YL: You recently did a residency at the Banff Centre. Are there ways in which these Icelandic traditions found a way into your work there?

DA: This summer I was working a lot, digging a little bit deeper into paganism, magic and witchcraft. I read old manuscripts about these traditions, took those descriptions and tried to recreate some of the objects—because the objects have never been found and you only have the descriptions of them. The big nails, for example, were [initially] just a description I found in some ancient text. I also did a collaboration with a practicing witch from Montreal, Sandra Hubert, who is doing her PhD in witchcraft. We met there at Banff and had discussions about how to make magical objects that could connect or console people through their ritualistic meanings.

Dagmar Atladóttir, Goddesses, 2017. Stoneware and glaze. Deities modelled after the original fertility goddesses such as Venus of Willendorf. The ancient goddesses were often made to explode in the firings, whereas these goddesses act as kiln goddesses; protectors of the kiln. Survivalists.

YL: Ceramics isn’t the medium you started out with.

DA: No, it isn’t. I have a collaboration with a friend of mine, Laura d’Ors. We worked together for a long time, but distance makes it hard since she lives in another country. Our collaboration is called Atladóttir & d’Ors. Laura is Spanish and lives in Berlin. We liked to think about the primal forces of being a woman, the “brut” [essence, roughly] of being a woman. we created a country which is inhabited and run entirely by women. It is called the Independent Republic of Bellona.

Our idea was to see what would happen if you had a country of only women, where women run it and have to make all the decisions. As a solution, we decided that the men were explorers. So that’s why they’re not there: they have their own history. So it’s not to exclude, it’s just to think about what would happen. We have a fake Google Map, and our website is a fake Wikipedia. It’s a kind of speculation, a hypothesis maybe, and it’s also quite humourous. We thought of flags, clothes, food, and everything that makes a tradition. It follows the rules of world-building, which has been done so many times before, but it’s still an interesting methodology of working.

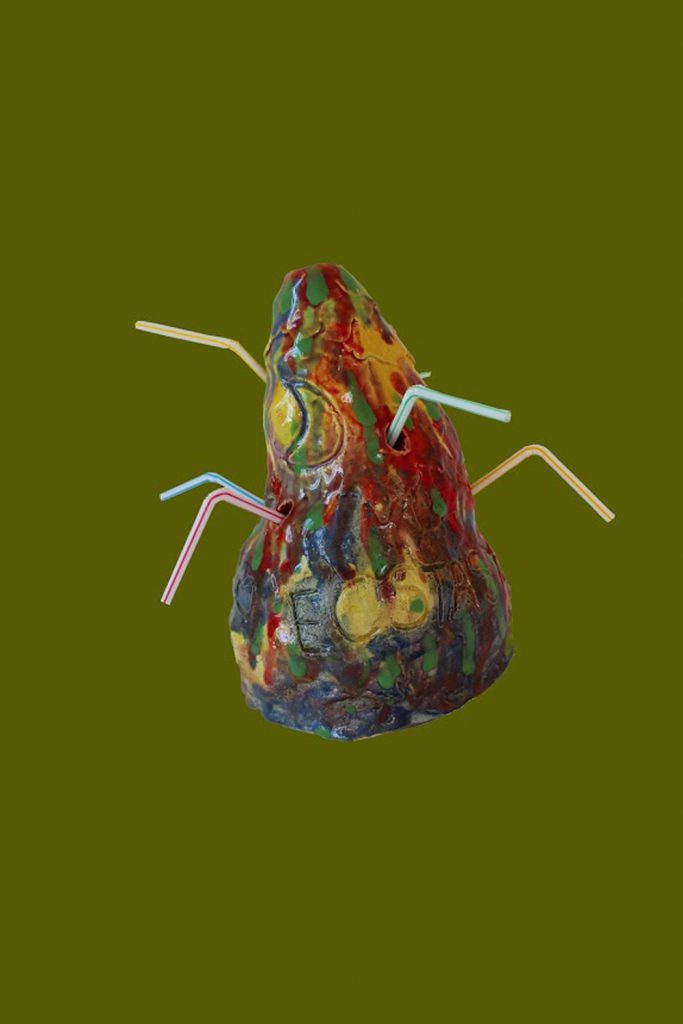

Dagmar Atladóttir, Ecstasy and kinship. from a collaborative project with Sandra Hubert, 2017. Stoneware and glaze. A communal cocktail sculpture, that reads ecstasy and kinship. Object was laced with spells and magic and words were manifested into the clay during kiln firing.

YL: You’ve talked about making “functional sculptures.” Did this idea of world-building influence the way you came to make objects?

DA: I think it’s very related to that because the object creates its own sort of world around it. What I like to do is performative pieces; I make the objects and then they kind of perform themselves. Once, I made a little restaurant in my studio. I made these spaghetti [bowls with faces] that puke spaghetti and the meatballs come out of the eyes. I cook the spaghetti and then I put it in the bowls and out of the mouth pukes the spaghetti.

It was an open day [when I was doing this performance], so the audience was coming into the studio, and I was preparing the meal slowly. Then, I would bring the meal out and then the piece was kind of performing itself, all I did was carry it to the table. Food always has to be so elegant, and so to make it a little bit disgusting, or to make it a different experience, was fun. This is kind of what I did with the sculptures this summer.

I wanted to enjoy things in a different way, which I think is a very honest way of doing stuff. It’s full of gimmicks and it’s full of spells and full of all these extra things. But when you break it down, you’re just enjoying things in a little bit of a different way.

Dagmar Atladóttir, Ðettó a restaurant performance, 2016. Stoneware and glaze. Made in the European Ceramic Work Centre. Dinner Bowls, spaghetti and Meatballs, and salad bowls from a series of performative tableware objects that do various horrible things such as puke, cry, and amplify sound.

YL: Where did you hone in on this kind of approach?

DA: I slowly started to transition [into it]. I did a master’s in applied arts at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam. I studied at the Dirty Art department, which is all about applying your practice to a real context. They put an emphasis on getting out of the museum and the gallery contexts and take [things] into real life. That interested me because I had been working with a gallery and a museum and I just thought, “Yeah, maybe it’s nice to think about other contexts to do your work in.” And so I started to find very interesting ways to make functional sculptures.

Dagmar Atladóttir, Salad bowl, 2016. Stoneware and glaze.

YL: And you were drawn to ceramics?

DA: I did a residency in the Netherlands two years ago at the European Ceramic Work Centre. I had no previous experience with ceramics so it’s there that I started. It’s like a palace: they have kilns [so big] that you can drive into them. You say: “I want to make this,” and then they help you to make whatever you want to make.

I wanted to work with horror. My idea was of horror as catharsis, you know, where you have to face your own mortality. And also this idea about the patriarchy having hijacked Friday the 13th, which used to be the great day of the goddess and now is this horribly fearful number. Thirteen is a very female-oriented number. For example the number 13 is the average annual cycle of women´s menstruation, and the average cycle of annual full moons. [Similarly with] Halloween, anything that is to be feared, or seen as illogical, is always translated as being of the feminine. I like to work from these “brut” ideas about femininity.

Dagmar Atladóttir, Goddesses, 2017. Stoneware and glaze.

YL: Is that idea of “brut” femininity how the Venus comes into some of your work? The Venus is a symbol of womanhood that exists across different cultures, in different ages.

DA: Those Venuses were made in prehistoric cultures all over the world. Some new researches claim that they were made to explode in the firing, but I make these Venus kiln-gods because it’s a tradition within ceramics, that perhaps even derives all the way back to the original Venuses. The tradition in ceramics is that you always make a kiln goddess or a god to be in your kiln, to kind of superstitiously protect the things that you’re making. And for me, working with clay is very much about alchemy. It’s very much about transforming the material. Mud is the most basic material, and it goes through so many stages. For me it’s like primitive alchemy.

Dagmar Atladóttir, Djinn Vase from UGLY MRCL Collection, 2016. Stoneware and glaze.

YL: We started by talking about pagan beliefs and practices. In your way of making objects are you, in a sense, bringing back these rituals?

DA: Yes, and really I enjoy this kind of rejected knowledge, which is superstition, invented traditions and all these things—where you just kind of reject a belief system, or even build a new one. Maybe playing around with twisting or forgetting western theory and going back to the primitive. The Non-Logic. I also really like to create scenes of entertainment. As light as a lot of people would think it is. I find it important.

Dagmar Atladóttir, Fuck Head, 2013. Plaster, oil paint, iron, concrete. A cyclopes from a series of speculative objects that hypothesize on future species of the planet.

Dagmar Atladóttir, Phantom Lamp from UGLY MRCL Collection, 2016. Stoneware and glaze.

Dagmar Atladóttir, Phantom Lamp from UGLY MRCL Collection, 2016. Stoneware and glaze.