Skateboarders have an uncanny knack for playing out of bounds, often to the chagrin of urban planners and institutional authorities. But for one night only last week, the Winnipeg Art Gallery threw out the rule book and transformed the gallery’s soaring atrium into a skateboard park, inviting local skaters and audiences alike to rethink the boundaries of public space. The occasion was the opening for “BoarderX,” an exhibition that unpacks the cultural, political and environmental influence of snowboarding, skateboarding and surfing on the practices of seven contemporary Indigenous artists: Jordan Bennett, Roger Crait, Steven Thomas Davies, Mark Igloliorte, Mason Mashon, Meghann O’Brien and Les Ramsay. Here, curator Jaimie Isaac discusses the ideas behind the exhibition and how board sports inform a worldview that ranges beyond counterculture cool to reveal the deeper value of breaking the rules.

Skateboarder Cain Lambert from Winnipeg’s Sk8 Skates at the opening for “BoarderX.” Photo: Leif Norman.

Skateboarder Cain Lambert from Winnipeg’s Sk8 Skates at the opening for “BoarderX.” Photo: Leif Norman.

Bryne McLaughlin: “BoarderX” uses snowboarding, skateboarding and surfing as a cultural lens on how artists respond to ideas of space and identity. Maybe we can start by talking about your own connections to board practices and how that informed your thinking around the show.

Jaimie Isaac: Okay. I’m of Anishinaabe heritage from the Sagkeeng First Nation on my mom’s side. I’ve never lived there, but I spent a lot of weekends there as a kid. My dad is British, first-generation. I think I was about 11 when I started snowboarding. Watching snowboarding videos really informed my style, the music I listened to, the clothes that I wore and the places I wanted to travel to. And it was a really good outlet for me to place myself in belonging to a community. I started skateboarding later, but both were really important to how I spent my time and who I spent my time with. It still determines where we travel as a family to go snowboarding. More recently I started surfing. That was an incredible experience. All of these sports are extremely humbling.

BM: Humbling in what way?

JI: Humbling because each sport is impossible in its own way from the start. I don’t know anyone, for example, who starts surfing and gets up on the board and is good to go. You realize how powerful the element of water is because you are getting humbled every time a wave comes—if you don’t know how to duck dive, you’re going to be in the wash and swallow lots of water. So you quickly recognize how small you are in the larger scheme of things.

With snowboarding and skateboarding, it’s actually creative because you’re looking at the mountain or city landscape and thinking about different ways of engaging with it. With skateboarding, especially, it’s a total critique of space or a re-reading of how to use a space that was designed for other things. It’s about thinking through a lens of creativity and performance, and intervening on intended uses or values. One skateboarder can be completely different than another in how they are creative with the space and perform. That’s why I really wanted an in-situ installation—a skateboard half-pipe—to be part of the exhibition to see how different people would relate to the space in new ways. There’s even a mini-Winnipeg Art Gallery that can be skateboarded on as a grind box. That turned out beautifully—it’s now super-scuffed. It was really great to see skateboarders ride it at the opening…there was this Godzilla-like affect.

A skateboard grind box in the shape of the Winnipeg Art Gallery as part of the opening-night skate park for “BoarderX.” Photo: Jaimie Isaac.

A skateboard grind box in the shape of the Winnipeg Art Gallery as part of the opening-night skate park for “BoarderX.” Photo: Jaimie Isaac.

BM: So how does this idea of spatial critique or creative intervention show up in the exhibition?

JI: I really wanted the exhibition to focus specifically on Indigenous artists that have or still snowboard, skateboard or surf, and how have woven that into their artistic practices—how they respond to the land, how they approach the politics of land and how those board practices really help to inform their world views and the ways they look at and respond to their environments.

I also wanted the exhibition to really reject the cult of cool or the stereotypical idea of a counterculture, especially in the perceptions around what skateboarding is, but also what skate art is. When people engage with skate graphics, for instance, they have a certain, set idea of what that represents. I wanted to use that counter-identity of skateboarding and these other board practices, but also turn on those expectations.

It’s the same way that the show challenges stereotypical ideas about Indigenous culture and people, their visual identities and what kind of art they should be creating or how that is representative of different ways of being. Skateboarding as a marginalized community, Indigenous artists as a marginalized community—there are a lot of parallels there that come about through the exhibition.

Les Ramsay, Goofy Foot, 2014.

Les Ramsay, Goofy Foot, 2014.

BM: So it’s about being marginalized and being anti-establishment, but also how this coheres into cultural and visual identities that run deeper and continuously challenge the norm?

JI: I think contemporary art in general should really challenge the structures and systems of being that we are currently confined to. I’m not saying that no one else has done this before using board cultures. Anthony Kiendl curated a show called “Godzilla vs. Skateboarders” in 2003 at the Dunlop Art Gallery that was about skateboarding as a critique of social spaces. In 2010, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian did “Ramp It Up,” which focused on Indigenous skateboarding culture in the States. But it hasn’t been something, at least that I know of, that has really focused on Indigenous artists that are also practitioners of these different board sports and who use that practice to make art that responds to the land.

For years as a girl skater, I kind of embodied going against these countercultural stereotypes: I can be a skateboarder but I can also wear some super high pumps and a great dress…I don’t have to be siloed into these perceived ideas of what skateboarding culture is. I think this also applies to this continued representative perception of Indigenous peoples. So I’m challenging that as well. Even having the skateboard in this kind of institutional space pushes what those institutions can be to different people; we can make it more accessible and challenge cultural experiences.

At the same time, the work that’s in the show—whether it’s weaving, carving, photography, mixed media or performative—is challenging the canon as well.

Meghann O’Brien, Sky Blanket, 2014. Courtesy Haida Heritage Center at Kaay Llangaay. Photo: Rolf Bettner.

Meghann O’Brien, Sky Blanket, 2014. Courtesy Haida Heritage Center at Kaay Llangaay. Photo: Rolf Bettner.

For example, Meghann O’Brien, who was a professional snowboarder, has a woven Chilkat blanket robe as part of her installation. She’s not making a traditional Chilkat blanket robe, where she’s talking about clans, lineages and family connections. She really thinks about the materiality of the mountain goat wool when she’s weaving. She’s talking about a contemporary way of engaging with the land. Mark Igloliorte, a skateboarder who has an Inuit heritage and grew up in Labrador, is showing the vinyl-cut image of a kayak on a skateboard deck that is positioned in between two films. One of the films it shows him in a kayak doing the motion of the Eskimo Roll; the other shows him doing a kickflip with a skateboard. It’s the same movement—performative and contextual. It’s not just about coolness; he’s looking at Inuit culture in a contemporary way. Like works by all of the artists in the exhibition, he’s activating a deep cultural knowledge that really bridges past and present.

BM: We were talking about how important it was to open up this space to new ideas. Aside from the exhibition, there’s an online component, #Xarticles, that is going to be regularly updated with a mix of blog posts and essays on topics like Indigenizing surf culture or skateboarders as elders, you’re running an amateur skate-video film festival at the WAG in the spring and a training workshop on how to make a skate deck from shaping the board to designing the graphics. At the opening last week, you built a skate park in the WAG’s atrium and invited local graffiti artists to paint the space and Indigenous skate team Red Riding Media to ride the ramps. That’s an amazingly ambitious program. How’s the response been so far?

JI: For me, all of this is an essential part of contemporary curating, because you’re activating the work and the concepts in a different way, you’re reaching new audiences and you’re making all of these ideas more accessible through tactile learning or different sensibilities of engagement. I think there were about 900 people at the opening. A lot of first timers came in the doors. What I really loved seeing were the different generations in the space. There were lots of kids, people in their 90s, different skate communities, people who used to do these board practices that were really engaged. It was just really great to have that ramp in that space. All night I overheard snippets of conversations about mobilizing this new generation of skateboarders, snowboarders and surfers who might now be coming into galleries and making art.

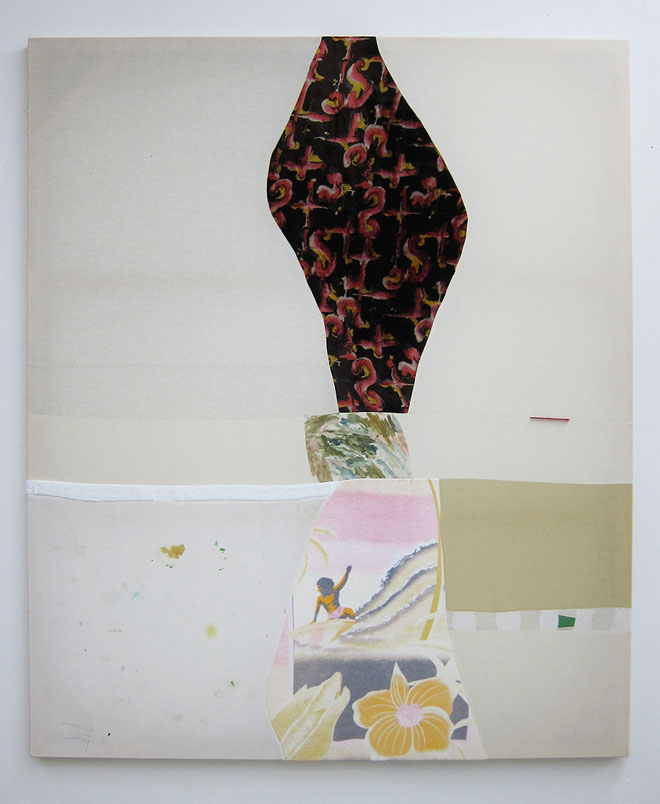

Jordan Bennett, Wo’kin, 2016.

Jordan Bennett, Wo’kin, 2016.

Mark Igloliorte, My Yellow Aquanaut 17’ 7”, 2016.

Mark Igloliorte, My Yellow Aquanaut 17’ 7”, 2016.