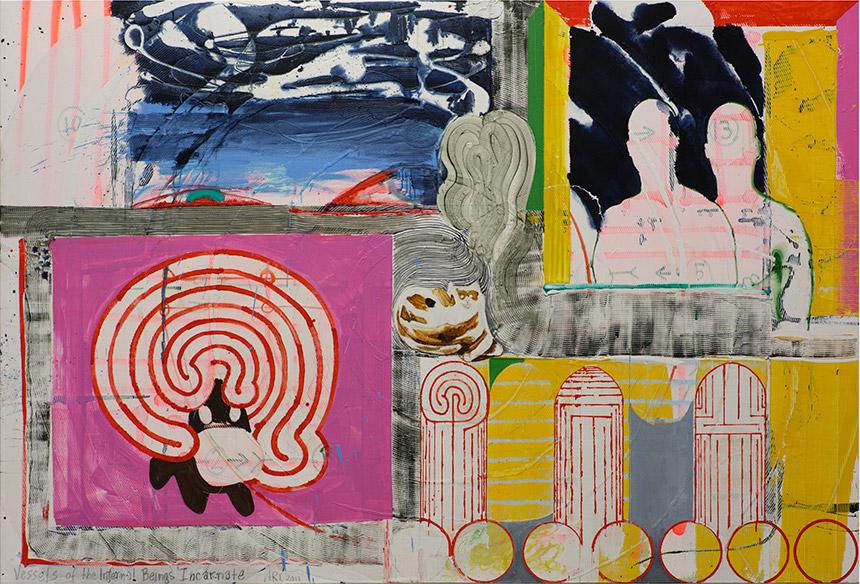

Recently, Attila Richard Lukacs debuted a strong new exhibition at Vancouver’s Winsor Gallery. The current body of work—a hybridization of abstraction, figuration and landscape—brings back traces of Lukacs’s earlier treatments while presenting something fresh. In this Vancouver studio interview with Noah Becker, Lukacs talks about gardens, Indian miniature painting, tantric methodology and more.

Noah Becker: In your new exhibition at Winsor Gallery, some of the works are landscapes that do not feature human figures, with water flowing through architectural formations. Other works show abstracted human forms, and gardens depicted with various mediums. How do you view the exhibition?

Attila Richard Lukacs: It’s a return to the gardens; the gardens were always a comfortable home for me as a painter. I also like how water developed as a theme in the work, and I carried it through. So when I look at these works, it really feels very new.

NB: This is a less figurative body of work, not as abstract as your recent grey paintings. Yet where figurative elements do appear, there is an unmistakable feeling of human presence. How do you handle the painterly drawing of the figure in these works?

ARL: The grey paintings were a lot about drawing: they were grisaille, grey monochromes, grey sketches, often with architectural elements in them. The grey paintings were very tantric and of the moment—tantric in the exercise of putting down a mark or a colour.

In the new work, it’s about how far you want to go with the figure. One of the underlying strings of the new work is also this tantric methodology of making a painting.

NB: About the garden theme in many of these works—do they represent the garden planted at the entrance to your studio, or is it just one aspect of the new work?

ARL: Well, some of these paintings go back to the Garden of Eden.

NB: Some of your earlier work also had Eastern influences, like the paintings in the exhibition “Of Monkeys and Men” in 2003. Your sense of composition in the new work uses elements of Indian miniature painting, right?

ARL: I’ve always felt that that’s also a comfortable place for me as a painter.

Yet I’ve always found those monkey paintings very abstract; they were underpinned by abstraction. It’s about colour and fields of colour; I always thought there was great modernity in them.

It’s not surprising that I see the influence of Eastern miniatures in De Kooning or in Picasso—they must have been looking at it too.

NB: Another interesting piece of yours is the sculpture that was exhibited at Winsor’s booth at Art Toronto in 2011. I hadn’t seen this kind of sculpture from you before—it had painterly elements, yet it was a floor-based work.

ARL: Yes, those were my bitumen pieces, and they were also, once again, tantric in their exercise—being about picking a mark and repeating that mark over and over. It’s an exercise of recording the history of the moment, letting it be of the moment.

NB: The figures in your new paintings are almost like apparitions or wraiths, and they have a strong element of repetition as well—repetition of silhouette or line. Were you interested in how figures would come back into the paintings, or did it just happen by accident?

ARL: I was interested in seeing how the figure would come back into the work. In many ways, it was still about repeating a mark and having shapes carry through the prosceniums.

As for the fountains or the prosceniums themselves, once again it is about the repetition of a shape or a silhouette to become perfect, to become an arc or a fountain. It becomes about repeating the exercise and the shape and the mark. It becomes a daily exercise, and then the compositions build out of themselves.

NB: You do seem to work daily, and your production level is constant. Is this consistency an important aspect of making your work?

ARL: Yes. It’s momentum that builds up in the studio. One mark really takes its place and carries into somewhere else, and you can feed that very fast and furiously.

It’s about the speed at which things are rolling, really. It takes over, sometimes, and things can happen very automatically. You can record a moment on the canvas and have something that becomes beautiful in itself.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This article was corrected on January 31, 2013. The original copy suggested that the exhibition opened during the week of January 21.