It seems to me—as a white, middle-class, cis, bi woman just past 40—that there has rarely ever been such a wide public discourse about the importance, and shortcomings, of queer spaces as there has been this summer.

The shootings at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub in June sparked the widespread publishing and sharing of articles like “Please Don’t Stop the Music,” which paid homage to Pulse in particular and gay bars in general.

This month in Toronto and Vancouver, Black Lives Matter asked that police floats be removed from their respective cities’ Pride Parades, among other reforms, highlighting that all queer spaces are not always safe for all queer people.

Also in the mix of queer-space news this summer: the small towns of Steinbach and Truro held their first Pride Parades, a sitting Prime Minister walked in a Pride Parade for the first time, and the gay-focused Canadian Rockies International Rodeo was cancelled due to financial concerns.

All these events and related dialogue were on my mind as I considered, from a distance, recent works by two artists with roots in Western Canada: Mark Clintberg and Kegan McFadden.

In early July, Clintberg created and installed a sign for a fictive gay bar called Détournement—a queer dance club / piano bar / nail bar / milk bar / library / vegetarian BBQ and crisis support centre—in the lower level of an historic Winnipeg building. The sign was installed in response to a commission at Winnipeg’s Window, a 24-hour artist-run windowspace co-programmed by McFadden and Divya Mehra.)

In late June, McFadden opened a show at Edmonton’s Latitude 53 titled “Exuberant Intimacy.” In the show, McFadden pays homage to platonic relationships with six men, bringing private desires into public-institutional space. The project builds on McFadden’s past projects around queer legacies—one such artwork, in 2014, detailed the disappearance of gay bars in Calgary.

Recently, I called Clintberg (who’s currently teaching at the Banff Centre) and McFadden (who’s based in Winnipeg) to talk about gay bars, queer futures and the forces of expansion and exclusion, disappearance and dissemination, that are simultaneously at work in LGBTQ communities today.

(And a note on language: the terms “gay” and “queer” are used in this article, among others related to sexuality, with the recognition that they are not terms to be used interchangeably.)

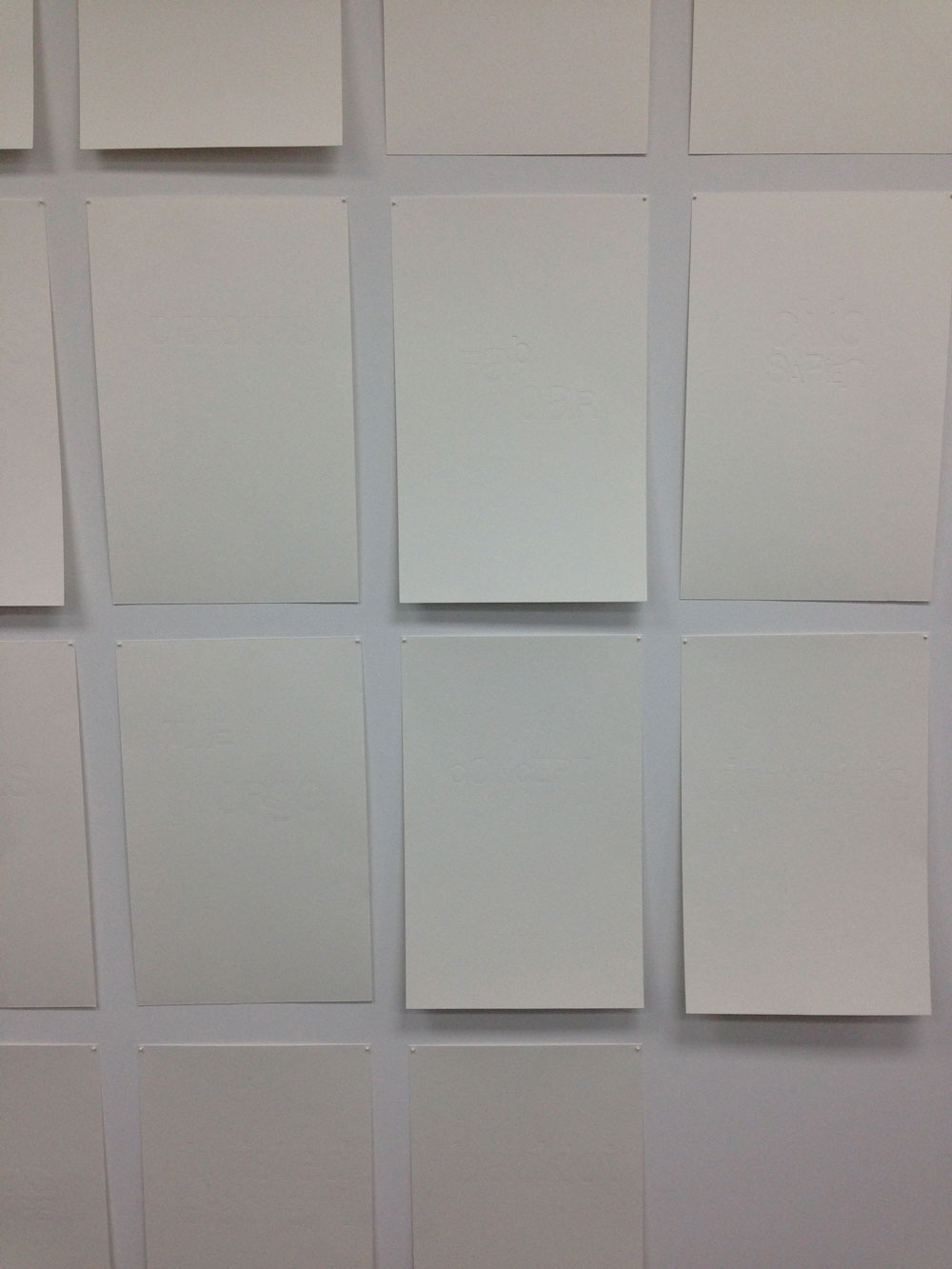

Kegan McFadden’s installation Recollections (2014) recorded the gay bars, restaurants, baths and cafes that have closed in Calgary from the mid-1980s onwards, rendering them as white letters on white sheets of paper. Image courtesy the artist.

Kegan McFadden’s installation Recollections (2014) recorded the gay bars, restaurants, baths and cafes that have closed in Calgary from the mid-1980s onwards, rendering them as white letters on white sheets of paper. Image courtesy the artist.

Leah Sandals: Both of you have made works recently that deal with the disappearance of gay bars. Why did you decide to do that?

Kegan McFadden: I did mine in 2014 as part of a group exhibition called “The Travelling Light,” curated by Steven Cottingham at the New Gallery in Calgary.

Steven named the show after a piece of public art that generated widespread popular and political outcry in Calgary. And for it, he asked artists to respond to themes like the effects of politics upon one’s personal life, and on civic memory.

So I proposed to look at all the gay bars and baths and restaurants that had come and gone in the same time frame of the New Gallery, which started up in the 1980s.

What I found was that in the mid-80s there were 18 gay clubs, baths, clubs and restaurants in Calgary; and that at the time of the show, in 2014, there were only three left.

What I ended up making was a kind of memorial that looked also like a white flag. It’s kind of this confused gesture; it could be a symbol of giving up, of surrender, but it was also in the shape of a triangle, so it referenced discrimination in a different way.

And though the show in Edmonton doesn’t reference gay bars in particular, one part of it does pay homage to Doug Melnyk, a mentor and artist who was part of artist-run culture in Winnipeg in the 1980s and who continues to make queer work unabashedly.

Mark Clintberg: Some of my ideas around this were sparked more recently, when I took a gay history tour with Kevin Allen, research lead on the Calgary Gay History Project.

I’d lived in Calgary before, about a decade ago, when there were a lot more gay bars in the city. When I returned, I was surprised how many had closed—especially one called Detour, where I used to go all the time. A lot of people in the art scene would go there after openings; it was a meeting place for people of so many different sexualities and genders, which I thought was really interesting, as Calgary is often cast as a backwater and not very progressive in terms of sexuality. I was quite sad to come back and learn that Detour had closed.

So I had already been thinking about the erosion of gay and lesbian spaces in Calgary, and I thought, for the project in Winnipeg, that maybe I would do something about this erosion of space.

Then, there were the mass shootings in Orlando in June, at Pulse. I was really distressed by that, as many other people were. It’s a real tragedy, and it feels like this real step backward in a way, to make public space feel really unsafe.

Pulse was a club I went to a couple of times when I was living and working in Florida a number of years ago, too. So I decided I wanted to do some kind of tribute to the people who were lost in that shooting.

Those two things were in my mind—Detour and Pulse—and then Kegan let me know that there was also a once gay bar in Winnipeg called Detour.

That triangulation really appealed to me, so I created the suggestion of a club called Détournement, that had been around since the 1960s in the basement of Winnipeg’s Artspace building.

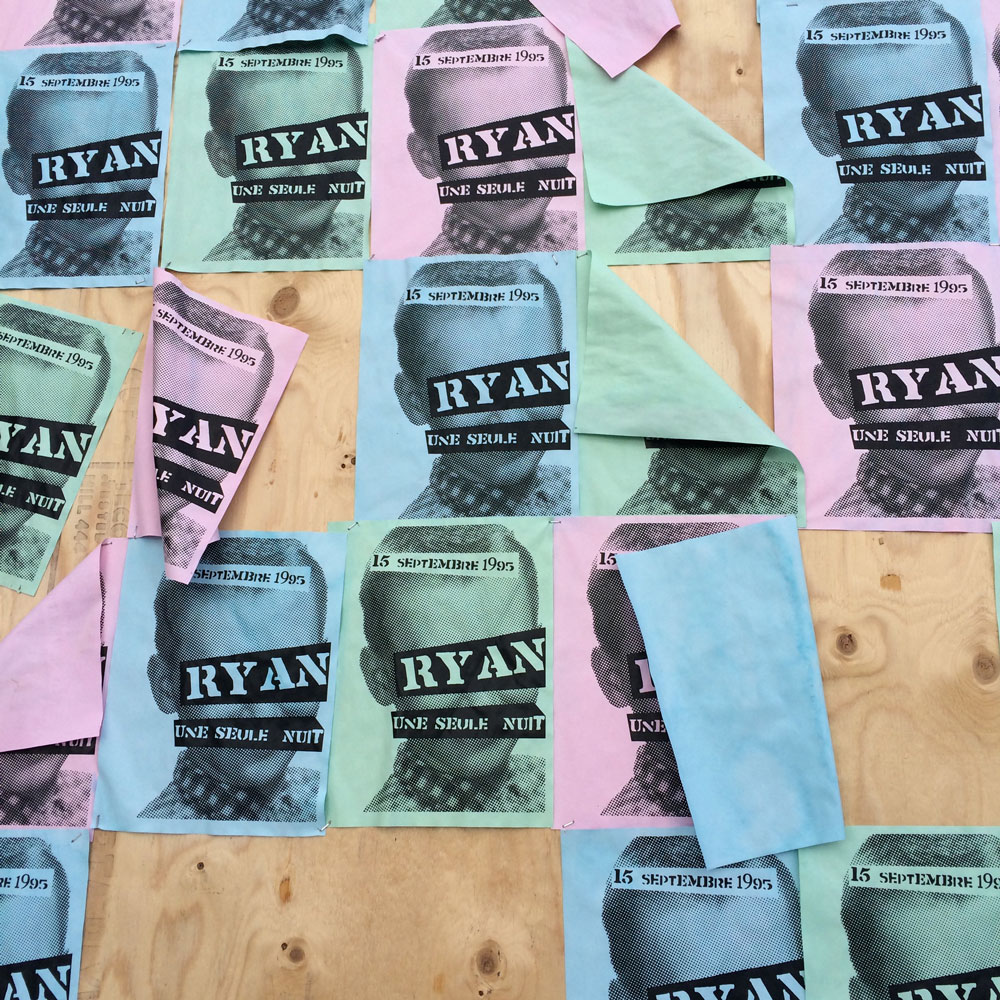

Kegan McFadden’s piece One Night Only, part of his summer show at Latitude 53 in Edmonton, pays homage to Ryan, a Franglais-speaking friend, by creating a clubland-style posters for a fictional concert. Image courtesy the artist.

Kegan McFadden’s piece One Night Only, part of his summer show at Latitude 53 in Edmonton, pays homage to Ryan, a Franglais-speaking friend, by creating a clubland-style posters for a fictional concert. Image courtesy the artist.

Leah: One question that comes up for me around the disappearance of gay and lesbian bars is, Why is this happening? What are your thoughts?

Mark: I have a few different ideas. Some are from theories already in wide circulation, others are more from lived experience.

I often hear people talk about how the use of such spaces has changed with the introduction of dating apps like Grindr and Scruff and Cuddlr (now Spoonr)—an app for cuddling.

That kind of argument says, well, we don’t really need gay- and lesbian-designated spaces anymore, because there are these apps which are more powerful ways of meeting people, and of filtering the people one wants to meet.

But I see that as a really shallow explanation as to why gay and lesbian spaces are—well, I don’t want to say disappearing, but why there are fewer and fewer of them.

To me, it is more about the normalization of homosexuality in public space.

The project now up in Winnipeg is, in part, about the de-politicization of sexuality in North America. On that tour with Kevin Allen in Calgary, I learned that in the 80s, in that city, there was this division in the gay and lesbian community between people who wanted to integrate more into sexually normative society, and the people who wanted to remain completely outside of the sphere of normative sexuality.

That is something I see as a push-pull relationship for myself in my own personal life. There’s a desire to remain radicalized as an individual, but I also feel the impulse to sort of fit in on a certain level.

But I think there are so many different ways of radicalizing. I think sexuality is one, and vegetarianism is another—that’s why the Détournement sign has a vegetarian BBQ on it. There are others, too.

And I think that there are lots of ways that this depoliticization is happening [beyond the phenomenon of there being fewer gay and lesbian bars]. There are definitely a lot of interesting debates around it, still, with the legalization of same-sex unions being a kind of linchpin related to this question.

Kegan: As Mark said, things like apps usually take the brunt of the blame.

One thing I love mentioning in discussions around queer bars is how intergenerational they can be. It’s a place where people of all ages and genders have mixed. I’m not sure how that adds to the conversation around why they are closing. But that intergenerationality was also something I wanted to honour in my show in Edmonton.

And I think also, around this point of radicalization, that it’s worth noting that to run a bar is a business. Corporatization and capitalism play a role, right? So if queer people are generally underemployed relative to straight, heteronormative situations, then they will have less disposable income, and they will not be able to write big cheques to keep their favourite bar open.

Steinbach, Manitoba, hosted its first Pride Parade this year. Artist Kegan McFadden was struck by the fact that a two-spirit group provided the only music in the parade.

Steinbach, Manitoba, hosted its first Pride Parade this year. Artist Kegan McFadden was struck by the fact that a two-spirit group provided the only music in the parade.

Leah: While I know you both have an interest in looking at private, intimate queer spaces in your art as well as public queer spaces, there’s so much that makes me want to focus on the public side in this discussion. Those new Pride Parades in Steinbach and Truro, to me, symbolize an expansion of safe queer spaces to some rural areas. At the same time, Black Lives Matter’s request of Pride reforms in Toronto and Vancouver underlines the fact that there is exclusion within supposedly inclusive spaces. What are your thoughts on these recent events?

Kegan: Well, the first thing that comes to mind was that I actually wasn’t able to attend Steinbach Pride. But I heard some people say, “Oh, it was amazing, because there was no music.” Steinbach was traditionally a town of Mennonites, so dancing was not allowed.

But what there actually was in Steinbach was Indigenous drumming throughout the parade, from a two-spirit group. To me, that seemed a parallel to Black Lives Matter at Toronto Pride—that the most radical aspect of Steinbach Pride came from the Indigenous people of Manitoba.

Mark: I think there are all kinds of spheres of exclusion at play. Sexuality is one, race is one, gender is one, class is another one. I think there are lots of forms of discrimination associated with those spheres of exclusion.

This situation makes me think about some core ideas in feminist and queer theory, like that there is no true equity or equality until there is equity and equality for everyone.

And the idea of alliance is really important. It’s something talked about a lot in queer circles. For me, that’s important to keep in mind around spheres of exclusion surrounding race.

For someone like me, who is middle-class and Caucasian, and had access to a post-secondary education, and also happens to be queer—all those things compose my place in society. There are ways that I am privileged. And for those of us who have more privileged spheres of identity, I think it’s really important to stand in alliance with people who have been excluded.

Of course, even inside of the gay and lesbian community, there is racism, there is transphobia. Those things are at play even inside of spaces that might be considered “anything goes.”

So I don’t see the queer bar, something we have talked about a lot here, as being a microtopia that has no flaws. It’s not that I think it is like paradise, or like a utopia. Far from it.

Installation view of Kegan McFadden’s show “Exuberant Intimacy” at Latitude 53 in Edmonton. The show pays tribute to McFadden’s relationships with six men, bringing private desires into public-institutional space. Image courtesy the artist.

Installation view of Kegan McFadden’s show “Exuberant Intimacy” at Latitude 53 in Edmonton. The show pays tribute to McFadden’s relationships with six men, bringing private desires into public-institutional space. Image courtesy the artist.

Leah: So where do we go from here? What’s a way into the future?

Kegan: One thing I think it’s important to talk about is bringing the past into the present and the future.

Mark’s Détournement sign is installed at a building close to the site of the 1919 General Strike, which adds another layer of rebellion and class wars. And the word Détournement of course references the Situationist International and May 1968. It’s a very smart, layered work, and the idea of it spurring a kind of alternate reality where the imagination can run wild is so important.

On a more personal level, one work I recently created is for a friend of mine, Ryan, titled One Night Only. It’s looks like a poster for a one-night engagement with a band called Ryan. The band is fictional, and the night never happened. The posters are in French, English and Franglais. Ryan liked to speak Franglais.

That layer of language is where Mark and I share a lot in common.

Mark: One idea circulating about language since the Enlightenment is that language is a tool for knowledge, for understanding, for truth-telling.

Kegan and I are using language for the creation of fantasy, like an imaginary or alternate history—one that’s important to reflect upon in order to figure out where we are at now, and where we might go next, to imagine a kind of queer future.

I’m not inventing that that term, queer future; that has been used by other people. And I think it’s something to plan for. We make financial plans in our lives, and scholastic plans in our lives, and it is important for people who identify as queer and queer allies to think about what a queer future would look like.

With 2017 [the 150th anniversary of Canada’s founding] coming up, it’s particularly important to imagine what a queer future will look like in the next 150 years of this geopolitical area. If we are dissatisfied with how practices of discrimination and exclusion are at work right now, then we need to make a plan for the future. How we are going to do that?

So I think part of our role as artists could be mapping a fantasy version of that vision, in order to get people to broaden the spectrum of what they think is possible in a queer future.

But at the same time, I hope people walk away from our projects with a sense of an homage to the memory of queer people who have come before us, who have dedicated their lives, or at least a considerable amount of time and work, to the same kind of politics that Kegan and I are promoting. We are inheritors of that legacy, and it’s our responsibility to move that forward.

Mark Clintberg’s signage installation continues until July 31 at Window in Winnipeg. Kegan McFadden’s “Exuberant Intimacy” continues until July 30 at Latitude 53 in Edmonton.

This interview has been edited and condensed.