Tran calls herself Trish, two Trans she says, as I hoist my fat legs onto the towel-clothed footstool, and watch her watch the gauntlet of girls in their surgical masks and try to find Lynn and Cindy and Kim who loves Adele, so beautiful is her music!

What colour? Tran says, and I tell her to cut at my dinosaur toes, sand and lube them, and paint them black.

My wellness—a seventeen-year-old Jack Russell Terrier—is gone.

Last seen lying on a pad, his paw wrapped in a blue bandage with a heart appliqué, his life leaking through an amber-coloured tube.

Twitching long after his death how he, unable to walk anymore, ran after balls and rats in his sleep and then near the end leaving a spray of blood on the pillows I worship as my Lourdes. Holy, too, his absence and lingering smell of corn chips and bone marrow.

Tran, there is no Heaven, I say.

Is it Sue who looks at me across the Nakdong River, through opaque safety glasses?

Look at them all kneeling before the monstrous temple that is me and four other iceberg-pale broads, with our filthy paw pads and yellow spatulate toenails; notice the rough, ragged heels and the stench!

All day they kneel, unassisted—how great their pain will be in just ten years—before chicken-white pegs like a skid of oleomargarine peppered with pre-cancerous moles and dense, neglected black hairs.

Kim’s grandmother was murdered during the Korean War in Sinchon: I translate this lyric for her on my phone.

But I set fire to the rain.

Watched it pour as I touched your face.

Well, it burned while I cried

’Cause I heard it screaming out your name, your name.

Kim never knew her mother’s mother, who was fleeing from a sky of black explosions and grey, fatal shrieks and white obliterating lightning.

I used to watch M*A*S*H which was especially horrible in its last seasons, possibly brilliant if you consider its eleven-year run > the Korean War’s three-year run.

M*A*S*H, I tell Tran, was a show about a US Army mobile surgical hospital during the Korean War, featuring a cast of libidinous white men (“meatball surgeons”), their assistants, a tiny psychic and a cross-dressing man desperately seeking a Section Eight. Occasionally the doctors, who drank heavily, had nightmares about rowing in lakes of blood. Sound funny, she says, or is it, Kim, Sue?

A girl calls as Sue paints my eyebrows and asks if she can bring her dog. My heart fills with shrapnel.

I signed the form with a shaky hand and the form said, OK, kill my dog.

I took away everything he had, is what I tell Sue, as she leans over me with surgical tweezers.

She says nothing. She gets one day off a week, and is never sure which. Her legs are just starting to ache at night, something lemon-drop cocktails take care of.

I want to know everything, having lost everything.

Cut his nails please I am scared, and leave them for me.

A week has passed and my dog is being burned. I am not at all well, I tell Tran, I mean Trish. In my dreams she rips off her mask and her mouth is filled with blood that sprays me as she says, I know, I know, like her grandmother said to her mother and her mother said to her. When really, she is letting my black nails dry and shoves me off.

Wait, not even a painted heart?

I shuffle home, my toes still separated by sponges so anxious are they to turn us over and wait and wait until the day belongs to them.

All these pretty girls wearing their history like a bridal train; all these steely-strong women!

You gave me my heart is what I would tell them, if they would listen.

Lynn you so fashion, Tran says, why you wear a wig?

If only I could pull out the knife that obstructs my breathing, but the poor blade has been waiting so long.

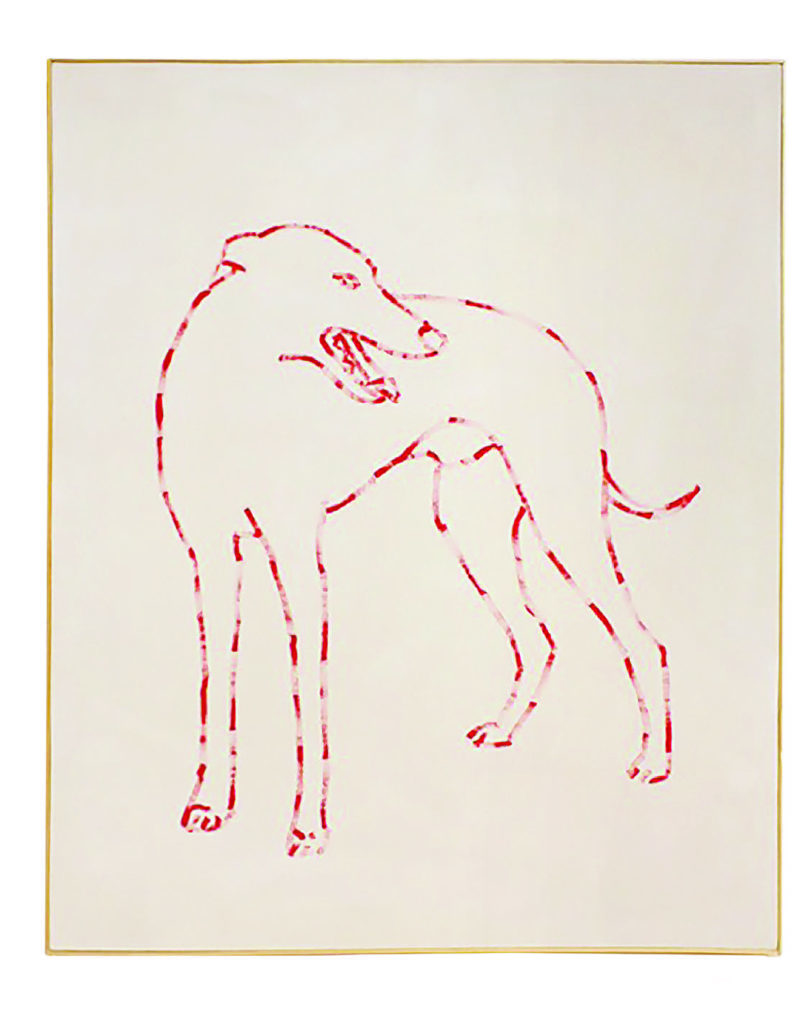

Jillian Kay Ross, dog 1, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 1.52 x 1.21 m. Courtesy Division Gallery.

Jillian Kay Ross, dog 1, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 1.52 x 1.21 m. Courtesy Division Gallery.