Final descent into Igloolik and I’m feeling the cold already. It’s seeping into the plane, into the soles of my feet, stiffening my knuckles and knees. It seems to be reaching out toward me, and I find myself thinking about the story a man told me an hour ago in Iqaluit, just prior to departure. Joseph Palluq was sitting beside me on the shuttle from the terminal to the plane. He turned to me, spotting a first-time visitor to the Arctic, and decided I needed to hear his story about hypothermia.

Perfect timing. I’d just been telling him I was up there with the photographer Donald Weber to visit the Inuit filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk. “You guys know Zach?” Palluq asked. I said no, but that we were interviewing him about his new film, Qapirangajuq: Inuit Knowledge and Climate Change.

“Huh,” Palluq said, impressed. It meant something that two “southerners” would travel all that way to talk to a man he’s known since grade school, a man who may now be Nunavut’s most famous citizen. Then, apropos of climate change, along came the story about hypothermia.

Palluq had been a teenager when it happened. The weather had been mild that day, so he’d dressed only in a light jacket when he went out with the dog team. A few hours later, far off on the land, the weather radically worsened. The wind picked up. The snow started. The dogs lay down in the mounting drifts and refused to move. He was stranded. And by the time 12 hours had gone by, he knew what was happening to him. He knew the symptoms: first you shiver, then you start stumbling. Pretty soon you can’t walk.

Palluq scratched late-day silver stubble, reaching this point in the story. He lives in Ottawa now, he’d told me. He was going back to Igloolik for his father’s funeral. I wondered if this sad journey had reminded him that the man he was about to bury once saved his life.

“Then, they found me,” Palluq said.

“Where?” I asked. “How far from Igloolik had you wandered?”

Palluq tried to explain. He said, “You know the ridge above town? You know the rock outcropping past that? You know…” He stopped, looking at me again. “But you’ve never been to Igloolik before.”

“No. I haven’t.”

He shrugged. He smiled. “Ah, well.” Then he drifted away.

I’m thinking about this last comment as the landing gear drops, as the ground nears in a blur of white and blue, as we thump to the ground, as the Igloolik Airport hurtles by in a rainbow spray of ice crystals. I’m minutes from finding out my luggage is still in Iqaluit—a separate matter. Looking out of the window, I’m thinking about what Joseph Palluq told me, and I think I know what he meant. He wasn’t being dismissive. He was only saying: if you’ve never been to Igloolik, if you don’t know the ridges and the outcroppings, the line of the shore and the way the tongue drifts form in the winter season, how could I possibly explain where exactly I was when my father found me, half-dead and about to slip permanently into the very heart of this cold?

The Inuit landscape is Inuit knowledge, I’ve read. And this idea is critical to Kunuk’s work. In Qapirangajuq, he did something nobody had done before, though it now seems obvious. He let Inuit elders talk about the landscape—the land, the sky, the wind, the water, the ice and the animals—that they have spent a lifetime watching. He let them map their own experiences of climate change. No biologists or meteorologists. No scientific explanations. Just those voices and the steady Kunuk lens, which viewers will recognize from his films Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001) and The Journals of Knud Rasmussen (2006)—a calm frame in which traditional knowledge survives amid modern pressures.

The elders speak, in Inuktitut words like the sound of water tumbling over round stones, and their voices weave into a braid of common wisdom, which stems from watching the environment. All Inuit are taught from the time they’re kids to check the weather each morning. The Inuk environment didn’t figuratively shape the community, then. It literally framed the possible. And so, as that environment has started to change—the atmosphere heating more rapidly here than in any other place on earth—tremors are felt at the very core of Inuit culture.

Kunuk meets us at the airport. Born in 1957 to a family still living on the land in qammaq sod houses, he was nine years old when he moved to Igloolik for school. He has lived on both sides of the traditional-modern divide. But after picking up his first camera in 1981 (a Sanyo colour with a Portapak), Kunuk began a video-art project that would keep one foot in each camp forever. Today, at 53, Kunuk is an internationally known figure, having received senior film accolades, including a Caméra d’or at Cannes. All the while, he has carried on life in Igloolik, hunting and socializing and raising his family, largely disregarding this global acclaim.

A sturdy man of medium build, he meets us dressed only in a black-and-grey lumberjack shirt, jeans and heavy boots. His Jeep is candy-apple red and, in this hamlet of nearly 2,000 people, Kunuk waves or nods to everyone we pass, from elders to kids trudging along the hardpack roads in hoodies and toques—no mitts—faces mottled across the cheekbones by repeated deep-tissue encounters with frost.

“Let me show you the community,” he says. So Kunuk, Weber and I drive from one end of it to the other, a couple hundred timber-frame buildings strung along a crescent beach opening southeast onto Foxe Basin. Kunuk shows us the medical clinic, the youth centre and the research station that looks like a UFO mounted on top of a pole. We drive all the way through town and on toward the dump, where the enormous ravens gather and stray dogs go to die. Our plan is to visit the hilltop cemetery where the grave markers date back 300 years, but we can’t make it up the grade—Kunuk’s four-wheel drive was taken out by a rock last summer. We slip and skid, then turn around and head back toward the hamlet.

He tells stories—he’s not reticent, as I’d been half-expecting based on other interviews I’d read. Far away from home, Kunuk is capable of going monosyllabic, but at the wheel of his Jeep, tooling around his own town, a speck in the midst of Nunavut’s vastness, he is in the place that defines him and his work just as surely as wind direction and cloud formation have always defined the Inuk day. He has tales to tell in this place. And one sticks with me powerfully, for how it brings to mind the vast distance we’ve crossed to get here, a distance measured not only in kilometres but also in centuries.

It’s a story about his grandchildren. Two of them, a boy and a girl, have been hurt in separate accidents in the past couple of weeks. Not seriously, but there was a broken leg in the case of the grandson. Kunuk darkens as he tells us this story. The coincidence doesn’t sit well with him. It is as if he senses that the ancient forces are still alive in the contemporary world. When I ask him what he is thinking, he doesn’t answer right away. Finally, he says, “In the old days, it would have been a message. Today, I don’t think it’s worth it to think so.”

Then he laughs what I’ll come to appreciate as a signature laugh, a high staccato chuckle with a Player’s tobacco note that fades down to a murmur, a sigh, a last letting-go.

I struggle to sleep, as a southerner will. At midnight, the sky is opaque blue. Kids are still howling around town on their skidoos. When these sounds fade, there is silence for a while. Then a bumpety-bump, a clackety-clack moving on past my window and down toward the Northern Store. I get up, pull back the blinds and see a small boy running down the frozen road, hockey stick bouncing behind him. When I wake again later, in the small hours, I find a blush of rose still lingering at the vanishing edge of the visible.

In the morning, Kunuk meets me over at the IsumaTV office on the main road, which looks out over the bay. The operation has produced feature films, documentaries and a television series called Nunavut (Our Land) (1994–95), and its nerve centre is the upstairs editing suite, lined with maps of the Arctic and display cases full of the accumulated artefacts of Kunuk’s life and career. IsumaTV, which owns the rights to all Kunuk’s work, is in fact a new entity, since Kunuk’s film production house, Igloolik Isuma Productions, filed for receivership in Quebec in early July. But you would never guess that from the office itself, which still teems with the evidence of work done and work in progress: charts and maps relating to Kunuk’s newest film, about the Cree-Inuit wars, plus award statuettes, film posters, oil lamps, a polar-bear skull and a walrus penis bone, as well as the pair of rubber feet that the actor Natar Ungalaaq wore during the scene involving Atanarjuat’s famous naked run across the ice floes.

This office was also where Kunuk made Qapirangajuq with co-director Ian Mauro (an environmental science PhD, now Canada Research Chair at Mount Allison University) and the Igloolik elder Augustine Taqquraq, who was brought in to advise on the Inuktitut language and cultural matters, and who participated in the editing of the film. An anecdotal approach drives the documentary. “We all know how scientists talk,” Kunuk says. “We’ve been listening to them for years. But nobody listens to a 92-year-old man saying: ‘You think this is cold? It used to be a lot colder.’”

Kunuk and Mauro let the elders speak, and a remarkably consistent story emerged. The elders told of rising temperatures and thinning ice, disappearing icebergs and permafrost melting to the point that lakes were vanishing into the softened earth. These elders also spoke about the sun and stars, in a series of accounts that Mauro now describes as “mindblowing.” Across the Arctic, the same story: the stars were out of position and the sun was setting in the wrong place on the horizon. One elder observed that the sunset had moved from one side of a landmark mountaintop all the way over to the other, which led him and many elders to conclude that the axis of the earth has tilted.

Mauro investigated, contacting NASA and other experts, and determined that atmospheric refraction was the culprit. The air is heating rapidly in the North; when contrasted with cold surface temperatures, this causes a mirage that allows light to bend around the curvature of the earth. Inuit are now seeing the sun return above the horizon much earlier in the season, and in a different position than expected. These observations leave the impression that the earth has tilted. Proof of this refraction explains the visual anomalies that Kunuk hauntingly captures in the film: the sun shimmering and elongating unusually at the moment of its return after the long polar night.

This part of the story got plenty of press, understandably. Southerners—even those in big cities who never see the stars or notice the shape of the sun—quickly grasped the metaphoric and scientific significance of Inuit elders’ descriptions of the tilted axis of the earth. These elders had generated new insights into climate change ahead of the scientific community, and this shocked and inspired many. But the quieter aspect of Kunuk’s film, which unifies it artistically with his other work, is the way in which Qapirangajuq positions Inuit knowledge and its critical relationship to landscape as a fragile cultural artefact suspended in the spreading web of global modernity.

Tensions surrounding the Inuit hunt illustrate this point: long-sustainable Inuit traditions now face opposition from both scientists and environmentalists. The Inuit lost their seal-hide economy years ago due to urban liberal squeamishness. They’ve had to do battle over their right to harvest the bowhead whale, a conflict between Inuit knowledge and the scientific community that, Mauro reminds me, eventually resulted in the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans changing its population estimates “from 700 animals to more than 14,000 animals.” The looming issue at the moment is the polar bear: according to Inuit elders, polar bear populations are thriving, but many southerners believe the animals are on the brink of extinction.

This isn’t only an argument about numbers. As in all of his work, Kunuk situates this dispute in the cultural realm, in the dynamic at play between the South and North—a region he describes as having moved “from the Stone Age to the digital age in a single generation.” The Inuit have never hunted beyond what was required for survival; shamanism and its attendant taboos would have forbidden it. But in the Inuit cultural context, which was pre-individualistic and communal up until recent years, it also wouldn’t have made any sense to over-harvest for hoarding or trophy purposes.

From that long pattern of experience, meanwhile, a specific element of Inuit knowledge emerges: a conviction that populations can only be sustained through hunting. Since Inuit mythology espouses a highly enmeshed relationship between humans and animals, Inuit people will express this conviction in terms of the animal giving itself to the hunter so that its spirit might be recycled and other animals might be born. When we gather later that evening with a number of elders at Kunuk’s house, I hear the elder Abraham Ulayuruluk sing a traditional Inuit ajaja song expressing exactly this idea. “The great white one,” he sings of the polar bear, “surrenders himself to the end of my harpoon.” Kunuk, straddling that traditional-modern divide, is able to offer a smiling aside at this point, leaning over to me and saying: “Of course, the great white one doesn’t surrender unless the hunter does everything else exactly right.”

But in his office that day, Kunuk’s frustration shows when I bring up animal rights activism. “We’re a hunting culture,” he says. “We don’t farm animals. We kill animals. And our children watch animals being killed and being butchered. They watch that and they learn how to do it. And they want to learn.”

Kunuk’s pride in traditional and communal ways of life is evident in the comment. So too is his commitment to their preservation. In this respect, there is a pedagogical aspect to the IsumaTV undertaking. Episodes of Nunuvut (Our Land), set in the 1940s just prior to forced relocation, each highlight some traditional activity. You can watch these online and learn how to build stone or sod houses, hunt different animals and handle a dog team. Kunuk becomes even more enthusiastic when describing the sessions in which he gathered actors together to learn these traditions so that the films could depict them accurately. I get the impression that there’s hardly anything he’d rather do than sit with elders and learn old songs or the proper Inuktitut word for some object or concept that might otherwise be lost to history.

Walking around Igloolik, meanwhile, I sense the reach that Kunuk’s work has had in the community. He downplays it, saying, “My hunting buddies are still my hunting buddies.” But if you’ve watched his films closely, you recognize a surprising number of faces in town. Even people I don’t recognize turn out to have had off-camera roles, like the woman I speak with at the high school who is proud that she learned to sew traditional caribou-skin parkas while working in the wardrobe department for Atanarjuat.

At the same time, Kunuk’s role as a vocal proponent of community values highlights a paradox that—like the fragile suspension of Inuit tradition in that web of global modernity—places a unifying stamp on his work. It’s a paradox created by the artist himself. It requires a certain individual zeal, after all, to take on the job of conserving your community’s history. And it takes a thoroughly modern sense of self-confidence to be a film director. Kunuk is known for giving his actors a degree of freedom in interpreting scenes. Dialogue in the television series was almost entirely ad-libbed, a very Inuktitut-style approach that yielded gold on occasion. (I especially like the elders in episode four who, during a tea break while harvesting ice blocks, begin talking about a shamanistic intervention to kill Hitler.) At the same time, when pressed, Kunuk lets slip the following assessment, which is no doubt shared by many people who do the same job: “As a director, you end up doing everything.”

That push-pull tension between the individual and the community is captured pointedly in the first film to bring Kunuk really significant attention. Atanarjuat is a central myth in the Inuit tradition. Kunuk remembers hearing the story countless times as a boy, and before Paul Apak Angilirq’s early, tragic death from cancer, the Atanarjuat screenwriter spoke about how important the legend is, as it lives “right at the base roots of Inuit culture.” That foundational story is about shielding community from the pressures of the individual. Taboo provides protection: the Inuit must never rank personal ambition ahead of the group’s needs. In this particular story, a man named Sauri and his son Oki both lust for personal power. Sauri wishes for the leadership of the local clan. His son does also, to the point of killing his own father. At the end of the story, the hero, Atanarjuat—a man who is rival to Oki for the love of a woman, who has lost his only brother to murder, and who has himself narrowly escaped death by running naked across the ice—returns to the community, sets up an ambush and finally rids the community of evil by killing Oki.

But Atanarjuat doesn’t do that in the film. In Kunuk and Angilirq’s version of this tale, Atanarjuat returns to the community, sets up the ambush and finally rids the community of evil by not killing Oki. Instead, he smashes his club into the ice beside Oki’s head and declares: “The killing must stop.”

Explaining this crucial narrative decision, Kunuk points out that he and Angilirq sought elder approval for the change, and were surprised when the elders said, “absolutely, go ahead and make the change”—because when Inuit told stories traditionally, they were always changing things. “There’s the basic story,” Kunuk tells me. “But over the years, it changes. That’s how it becomes legend.”

Then, Kunuk adds: “When you have a revenge story, it’s never going to stop. It’ll keep on going: revenging and revenging and it’ll never stop. And Paul wanted to change that, to change that ending.”

Nobody knows whether the film would have brought Kunuk any more or less success with the original ending. But it is possible to say that the impulse to preserve tradition in this case—the telling of this important tale, the depiction of Inuit culture in a way that had never been done before, the galvanizing of a community in support—depended on an artist for whom Oki’s death would represent “revenge,” not justice. That is, it’s a modern artistic imagination that made this film, charged with the willingness to change, to evolve, to eschew conventional wisdom on occasion and to adapt with the times. And that seeming paradox on the part of the artist himself is what marks each of Kunuk’s films most indelibly: a sense of tradition being protected and nurtured in the hijacked train of history as it hurtles into the future.

The closing scenes from The Journals of Knud Rasmussen offer the most poignant illustration of this last point. In real life, Rasmussen’s men travelled from Greenland and came in contact with Avva, a shaman holding out against the widespread conversion of Inuit people to Christianity in the 1920s. Rasmussen’s journals, as enacted in the film, show Avva’s answers to various questions, including this one, to an inquiry about his shamanistic religion: “We believe happy people shouldn’t worry about hidden things. Our spirits are offended if we think too much.… All our customs come from life and turn towards life.… We follow our ancestors’ rules because they work.”

“Hidden things” is a powerful phrase in this religious context, and Kunuk deploys the real here in telling service of the art. Avva is explaining to the Greenlanders that there is a deeply pragmatic base to Inuit tradition and to the rituals and codes that sustain it. Inuit taboos draw on Inuit knowledge, in other words. It is a combined guide to practical living: how to hunt, how to marry, how to raise children. But what is necessary for its efficacy is that its logic remain hidden, that the rules, the taboos, the system of thought by which Inuit culture is maintained not be examined.

Kunuk the filmmaker, a storyteller looking deeply and probingly into the psychological history of his own people, cannot make art and accommodate that prohibition. His films compel precisely because they push right through to a full examination, to candor, to exposure and to revelation. And his willingness to do what traditional shamanism would forbid—to break the taboo—is what gives the closing sequence of this movie its power.

Avva finally dismisses his lifelong spirit companions, sending away in anguish those whom had formerly been called forth in joy. And to what final, catalyzing incident are we to trace his decision? To his daughter Apak’s conversion. Having shown shamanistic aptitude herself, Apak sets aside the traditional code. She crosses the distance between her father’s camp and that of Umik, the shaman-turned-priest. Her decision shatters Avva. But he has crucially enabled her, having introduced Apak to the possibility that she can choose her Self over the community of traditional beliefs and strictures.

In the final words exchanged between them, Kunuk invites a Dostoevskian reading of the poisonous power of human freedom:

Avva: “Why do you leave me weak like this?”

Apak: “I just want to eat and live.”

Avva: “Go eat with your friends, then.”

Apak: “Do I have a choice?”

All of the film—and, arguably, all of Kunuk’s work—hangs quivering on Apak’s question. Do I have a choice? If you acknowledge that there is a choice, the individual is born, hidden things are revealed and the community begins to crumble.

Avva’s silence is his surrender to that reality. And having received this new knowledge, this modern knowledge, Apak chooses.

My final day in Igloolik is Easter Sunday and it’s the coldest day yet. No thermometer required for this assessment. I just take my hand out of my glove and see how long it takes the skin to chill down to the pain threshold: 30 seconds, by my watch.

I check out the two Easter church services, knowing I won’t see Kunuk at either one. But if it’s the traditional-modern dichotomy you’re after, there are few better places in Igloolik to observe it. At St. Stephen Roman Catholic, I eat frozen raw caribou. Up at St. Matthias Anglican, where Kunuk went until he was old enough to make his own choices, I turn to greet the man sitting next to me and find myself shaking hands with Avva the shaman.

Afterward, out on the ice, there are games and contests. There’s tug-of-war and a dog-sled race. Kids are demonstrating how to snowboard with a parasail and a group of young men are tossing a harpoon. I notice that Kunuk is participating in this last activity, and I go over to watch. They’re throwing the harpoon at what appears to be an impossibly small target: a disposable coffee cup set up on the snow 30 feet away. When Kunuk takes his turn, I snap a picture, thinking again of Qapirangajuq. The name means “to spear strangely,” a hunting term used in spearfishing, when you aim just off a target in order to hit it. Augustine Taqquraq suggested it as the film’s title after being asked for an Inuktitut word for “refraction.”

What my picture doesn’t capture is Kunuk’s throw. He hefts the steel harpoon. I see his weight shift, his body coil. And then it’s in the air. One glinting second, maybe two.

Bullseye.

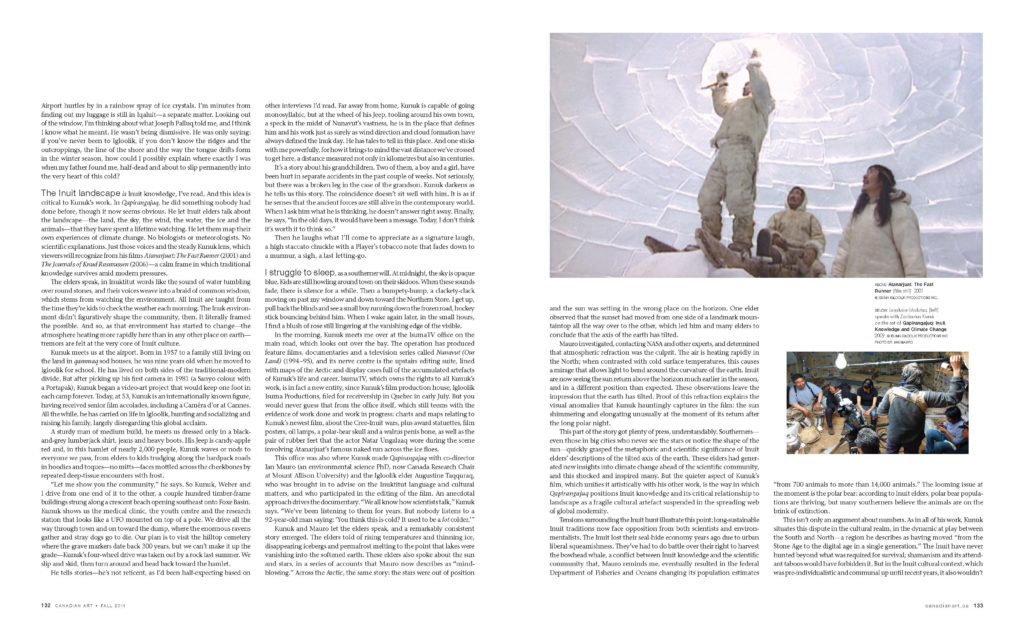

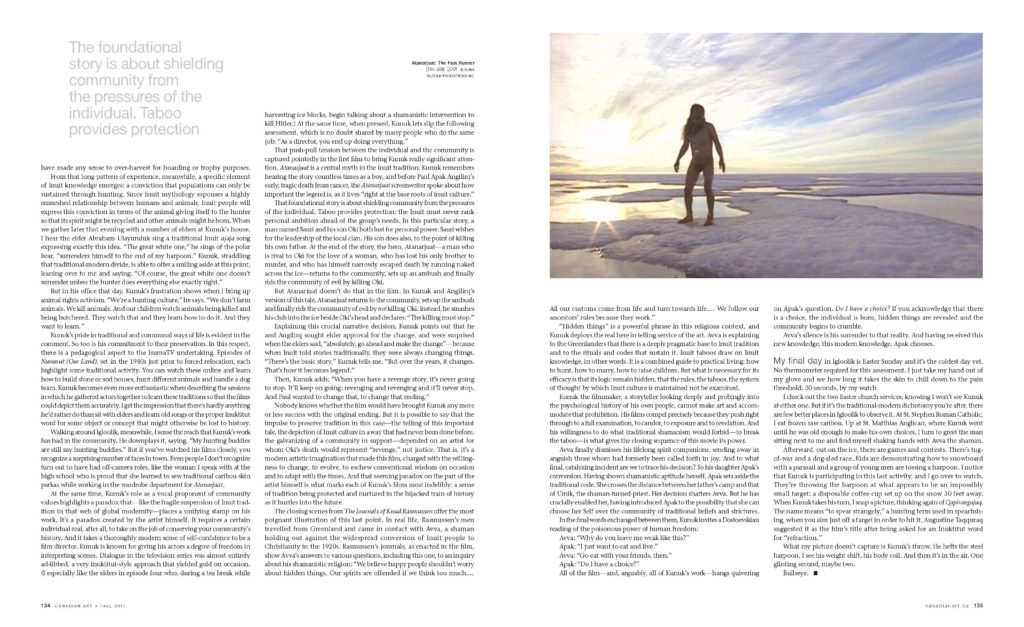

Zacharias Kunuk in Igloolik, Nunavut, April 2011, from the opening spread for “Man Standing” by Timothy Taylor in Canadian Art's Fall 2011 issue. Photo Donald Weber.

Zacharias Kunuk in Igloolik, Nunavut, April 2011, from the opening spread for “Man Standing” by Timothy Taylor in Canadian Art's Fall 2011 issue. Photo Donald Weber.