Within Sherman’s larger bodies of work, Untitled #549 reveals the ugly fault lines in the most radical of my generation’s feminist aspirations.

Catherine M. Soussloff

Cindy Sherman’s photographic installation Untitled #549 (2010) covers every inch of the gallery walls within the central hall of the first floor of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Six life-size representations of the same woman dressed in different, ostentatiously absurd costumes. Behind her, the backdrop of a wooded landscape repeats and invokes a certain pastoral placelessness, and a circular pan of the room makes one feel surrounded but not incorporated. The image folds over on itself in a lateral mirror image, similar to the famous Rorschach inkblot. By manipulating the background shot, Sherman achieves the ambiguity and ultimate boredom that repetition can sometimes create. The landscape becomes shorthand for the simulacrum. Nature seems to appropriate the bodies of these imaginary women, while the residual identity of the real woman—the artist—always lurks just behind them.

I met Sherman in Soho in 1989, when her photographs appeared to critique, through a kind of mirroring, the radical feminism of our generation. I had first encountered her work in 1980 at Metro Pictures. In today’s prevailing political environment, the figures of the grandes dames projected onto the Central Park backdrop—like some contemporary fête venitienne gone wrong—reflect back at me how profoundly unstable our presumed liberation has become. Compressed both into the picture’s foreground and the space of the viewer, the characters in Untitled #549 assume the undeserving grandiosity of an oversized paper doll. I see them for what they are: denunciations of canonical portraits and photographic conventions alike. They are also stand-ins for, or, more optimistically, what remains of the historical representation of an ideology of difference. The ideology of difference found liberation in the repetition of female stereotypes taken to their extremes, and in the masquerade that women assumed every day. Within Sherman’s larger bodies of work, Untitled #549 reveals the ugly fault lines in the most radical of my generation’s feminist aspirations. Literalized and consumed, these current repetitions of the masquerade might now be taken at face value, without the critical irony they once so clearly performed. The women figured in Untitled #549 stand before their viewers as the remnants of the political aspirations of a generation and urge us to make something more out of them than equivalences to images from earlier times.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #122, 1983. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #122, 1983. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Vikky Alexander

I moved to New York in the fall of 1979. At the time I was working with appropriated imagery, mainly from the editorial sections of fashion magazines. My gene pool of friends had quickly expanded from former teachers, CalArts alumni and fellow photo-based practitioners to include artists that exhibited at Metro Pictures, a small gallery in Soho that focused on the artists who later became known as the Pictures Generation. I’m sure that for at least five years I went to every opening at that gallery. My husband showed there, as did his friends, and friends of mine…. It was a very social time.

During that period I saw and enjoyed many of Cindy Sherman’s exhibitions at the gallery. The consistency of the rigour and imagination in her work always impressed me. With every exhibition she pushed her staged self-portraits to be different in style, scale and format from the previous series. How did she manage to be director, actor, stage and lighting manager, stylist, costume designer, editor AND innovator all at once?

There are many images of Sherman’s that I have loved over the years, but Untitled 122 (1983) from the Fashion series always stood out as a particular favourite. This woman is so angry. Even her suit looks angry. This image is anything BUT a fashion ad or an editorial with the usual message that the right clothes will give us the right man, and, as a result, make us happier and more fulfilled. Not for this woman. Her hair is a mess; her fists are clenched; her only visible eye is fixed on some jerk we can’t see. The expensive designer suit she’s wearing doesn’t make a damn bit of difference.

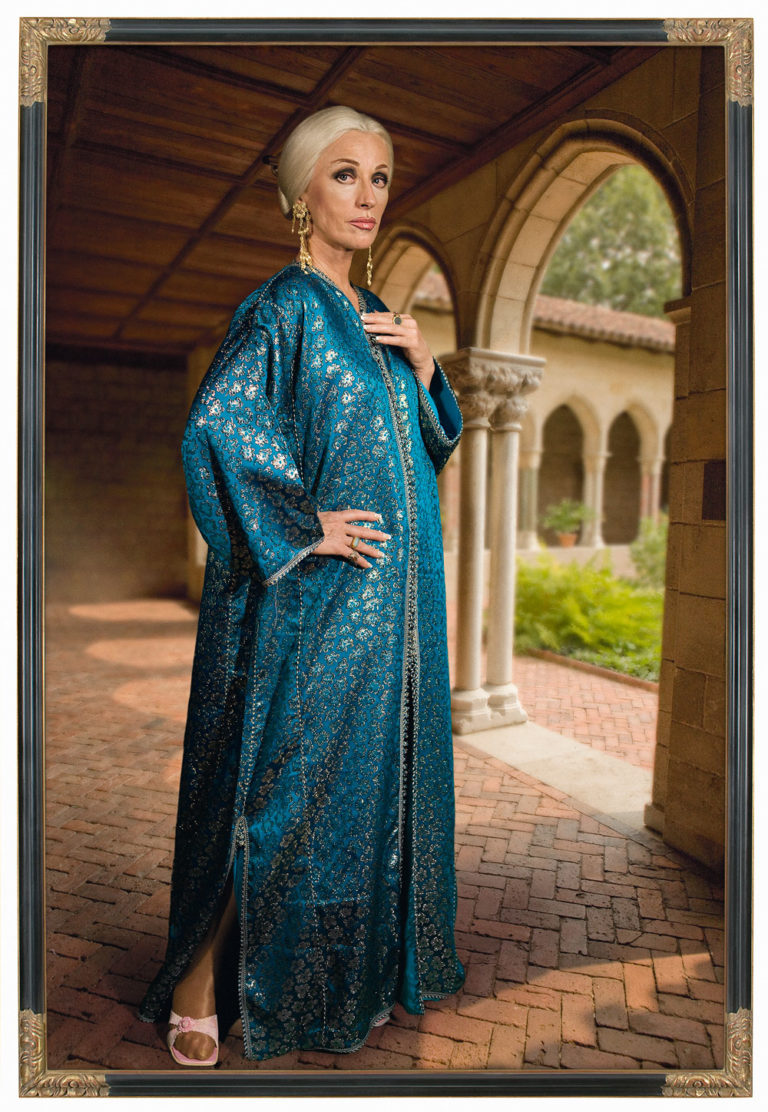

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #466, 2008. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #466, 2008. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Sara Cwynar

I love the society portraits because they are so much more complicated than they look. You can’t quite tell what you’re supposed to feel in looking at them. Are these women tragic or comical? They so clearly understand physical beauty as a—or even the—key factor of their success and value in the world, and they are clutching to the tail end of this beauty as they age. Or, are they strong, wealthy, regal and powerful in their own right? I love the combination of status markers, beauty and the grotesque—something Sherman does so well: we see liver spots and places where plastic surgery has gone wrong, but we also see opulent clothing and settings, women who are self-possessed, ready for the camera.

In my own work, I am thinking about morphing standards of style and beauty—how the things made with the most style are often the quickest to look absurd or sinister. Sherman shows how this can apply to actual bodies, to human faces. I am endlessly inspired by her manipulations of the vast range of ways that women present themselves and are presented through images. I love the society portraits even more now than when they first came out in 2008, because of the way plastic surgery standards have evolved and changed. There is a sameness to the looks of all the women in the series that reflects an older standard of plastic surgery—tight cheeks, raised up eyes, thin faces. Today we are in a different moment, one of Kardashian-inspired surgery-lite—fillers and glazes, huge injected lips, even (especially) for the very young. This aesthetic seems born of Instagram, and of influencer culture, but has also permeated the real world. In this new aesthetic, oppressive beauty standards masquerade as natural—fillers and endless skincare solutions and fake lashes and lips that allow us to pretend we put in no effort at all. Sherman’s pictures raise the question of how all these procedures will age, whom they are for and what they cost for women’s lives: she points out that even beauty is a trend, and that there might be a cost to succumbing to the latest craze.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #549 F, I, 2010. Pigment print on PhotoTex adhesive fabric. Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #549 F, I, 2010. Pigment print on PhotoTex adhesive fabric. Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York