A few minutes into Vincent Chevalier’s À Vancouver, we hear the artist’s voiceover: “When I came out as a teenager, Dad told me the story of his trip to Vancouver.” Accompanying this statement is a grainy scene of a passing landscape captured on Chevalier’s iPhone as he makes his way westward, on a bus, toward Vancouver. The scene was initially recorded using the VHS Cam app, which gives iPhone videos a retro look, and then re-recorded by the artist off a CRT monitor to give an added grainy effect—outside of time, or stuck, perhaps, between two times.

This scene in motion continues. Immediately after Chevalier’s remark, we hear his father’s voiceover: “I left Quebec City and hitchhiked to Vancouver with nothing but 40 dollars in my pocket.” Chevalier asks his father, rather earnestly, “Why Vancouver?” His father responds, “After that it’s the ocean. There’s nothing.” This dialogue, in English and subtitled in French, sets the stage for what follows: an intricately layered experimental video essay that combines documentary and fiction to explore the generational inheritance of trauma and the traumatic elements of both language and translation.

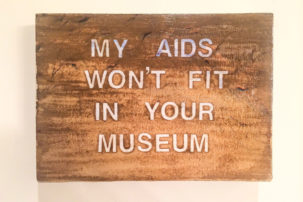

Space and time, geography and history, place and memory—these are the thematic strands in Chevalier’s art. Through them, he investigates the contemporary aesthetic realities of HIV and AIDS. Chevalier is HIV-positive himself and in earlier works, such as So…when did you figure out that you had AIDS? (2010), Your Nostalgia is Killing Me! (with Ian Bradley-Perrin, 2013) and Breeden (2014), he examines the uncanny as it affects the interplay between queer history and personal memory, and as it relates to the AIDS crisis—a sort of absence, or haunting, just beneath the surface. Following Chevalier’s thinking, my use of the term “uncanny” comes from Sigmund Freud, who in 1919 defined it as a kind of “frightening that goes back to what was once well known and long had been familiar.” Chevalier’s interdisciplinary body of work—which includes video, installation, performance, text- and image-based works, and found and appropriated material—addresses the uncanniness of queer history-making, which positions HIV and AIDS as nostalgic categories in both cultural memory and contemporary queer life.

À Vancouver continues to develop Chevalier’s earlier preoccupation with the frightening and the familiar. It also considers how translation, a tenuous thing, works on multiple levels to recalibrate the traumatic memory of the AIDS crisis. While it is now fashionable to use the reductive banner of “AIDS art” to romanticize the crisis—a response, perhaps, to the demands to memorialize it—Chevalier’s video essay tells a different story. It centres trauma, both cultural and personal, and in doing so poses a challenge to any easy attempt at commemoration. Chevalier’s approach reminds me of philosopher Rebecca Comay’s question regarding memory and the Holocaust: “How to commemorate an event which both demands and refuses commemoration; where all available cultural forms threaten to trivialise, sentimentalise, mystify, embellish, instrumentalise, or otherwise betray the memory of the dead; and where every attempt to acknowledge injury seems only to compound it”?

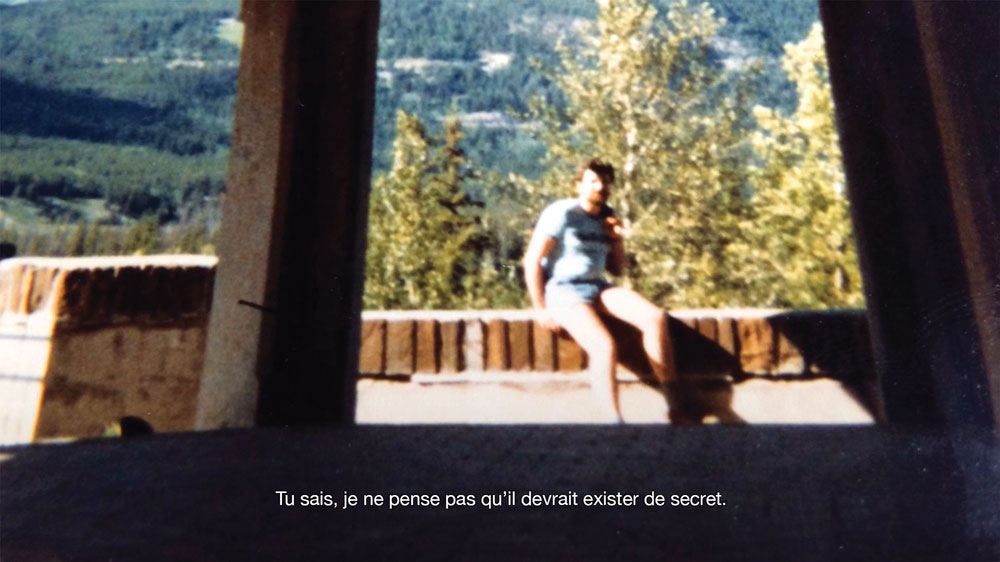

Vincent Chevalier, À Vancouver (still), 2016. Video. 34 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Vincent Chevalier, À Vancouver (still), 2016. Video. 34 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Vincent Chevalier, À Vancouver (still), 2016. Video. 34 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Vincent Chevalier, À Vancouver (still), 2016. Video. 34 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Vincent Chevalier, À Vancouver (still), 2016. Video. 34 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Vincent Chevalier, À Vancouver (still), 2016. Video. 34 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

In À Vancouver, Chevalier and his father recount events that inform both of their understandings of their respective sexual histories. The work also makes a connection between these personal histories, emphasizing the trans-generational passage of trauma from parent to child. Psychoanalytically speaking, trauma is excess material within the unconscious that is passed down and inherited. Chevalier’s video puts the genres of documentary and fiction alongside and against one another, exploring parallel events in the lives of both father and son. There is poignant, telling overlap. In Chevalier’s words: “They each traveled across Canada to Vancouver, and had formative (homo)sexual experiences at separate moments in time: my father as an eighteen-year-old traveling in the mid-1960s and [I] as a young teen and then adult in the mid-1990s [and] 2000s.”

In the opening sequence, Chevalier introduces a complex interplay between two languages, English and French, which also cleverly relates trans-generational trauma. These brief moments were shot immediately after Chevalier had made his cross-country trek, and he used a clear camera frame on an overcast day. In contrast to the en-route, grainy footage, here are crystalline still images of Vancouver buildings and landmarks. Against this brooding, melancholic backdrop, we hear the artist’s voiceover: “Quand j’étais jeune je draguais à Montréal. Les mecs me demandaient toujours si je venais de Vancouver. ‘T’es anglophone toé?’ Je répondais toujours: ‘Non. Mon père est Québécois…’” (“I used to cruise for sex in Montreal. Guys would always ask me if I was from Vancouver. ‘You’re English, aren’t you?’ I’d always reply: ‘No. My father is Québécois…’”—the translation offered here is as it appears in the English subtitles to the French voiceover). There is a pause before the artist continues his response, now in English: “‘…[but] my mother is from Vancouver’” (subtitles to this appear in French—“Mais ma mère vient de Vancouver.”). This intricate to-and-fro, a dance between English and French, between artist and father, between subtitles and voices, continues for the work’s duration. At times, the son speaks in English and the father responds in either French or English. At others, the father offers a remark in French and the son answers in either English or French. All utterances in one language are immediately and consequentially subtitled in the other.

The ellipses I put in the artist’s statements above reflect pauses in the video’s voiceover. They are ruptures, signalling a switch in the language the artist uses to tell his story, and elongating the time between the uses of the two languages. The ellipses also suggest to me the traversal of space and time: the journeys undertaken by the artist and his father occur at different points in their respective personal lives and in the context of Canada’s history—between the 1960s and the 1990s–2000s, the era of baby boomer radical politics and the present-day reverberations of the AIDS crisis, and also between Canada’s colonial past and its neocolonial present. Both of Canada’s official state languages signify its violent colonial history. The bilingual Chevalier, product of an English-Canadian mother and a Québécois father, journeys across the country’s geographic space precisely as he tells his story in and between languages.

The demand to remember feels inherently impossible, with every attempt to memorialize trauma, commemorate loss or relive the past doing the exact opposite of what it intends, and betraying the memory of what has been lost. Yet we persist in remembering through translation.

The journey in À Vancouver appears to be a critique of the concept of translatio studii(translation studies), a historiographical and deeply colonial idea with its origins in the Middle Ages, which claimed that the transfer of knowledge happened as humanity trekked westward. The work’s own study is, ultimately, of the trauma inherent in translation, in that trauma is precisely that thing which cannot be translated, which no language can capture fully. It rehearses succinctly what Comay has suggested: “Translation implies not only a spatial relay of psychic energy from one occupation zone to another [i.e., from one language to another]…[the] trauma [traumain-translation] marks a caesura in which the linear order of time is thrown out of sequence.” Implicit in the very demand to translate between languages is the impossibility of preserving what might be lost through the gesture. This is most immediately evident in the challenges we come across as we attempt to honour the preciseness of meaning and feeling found in one language, in another. The task of translation, in this sense, feels akin to the task of commemorating a historical event, such as the AIDS crisis. The demand to remember feels inherently impossible, with every attempt to memorialize trauma, commemorate loss or relive the past doing the exact opposite of what it intends, and betraying the memory of that which has been lost. And yet we persist in remembering through translation. As Comay writes, “The event is…at once acknowledged and disavowed. Its pressure is both registered and elided by being either consigned to the depths of the immemorial or pushed off to a future forever pending.”

The queer historian William Haver asserted that “what is called AIDS is, for consciousness and for thought, a necessarily impossible object.” Like the narrative challenges and the textual loss that translation involves, our capacity to commemorate AIDS can feel elusive. Monuments may be built, quilts may be woven, ribbons may be worn, but what do these gestures truly signify? It is this concern—regarding commemorative objects and the “impossible object” of AIDS—that Chevalier investigates in his next project, The Still Living End.

Director Gregg Araki’s 1992 cult film The Living End tells of a rage- and sex-filled road trip taken by two queer rebels and lovers, Luke and Jon, the former a drifter, the latter a film critic, both HIV-positive. There is nihilism to the film that reflects the time in which it was made, when a seropositive diagnosis meant a death sentence. Chevalier’s The Still Living End picks up where Araki left off. At the end of Araki’s film, his lovers are alone on a beach: silent, alienated, isolated and perhaps contemplating what will come next—what will remain of them. But Chevalier’s single-channel video is devoid of human actors, a “haunting tableau vivant or living ‘film still’ representing a group of props, arranged as if on the [set] of a film shoot.”

In Chevalier’s own words, “the visual and art historical reference for this collection of props is the vanitasof classical painting. Vanitas were lush and indulgent paintings, representing motifs of death and the transience of life.” And so Chevalier again takes on the question of translation—here, between the genres of painting and cinema, and of still life and the moving image. Araki’s stark world in The Living End signalled utter alienation and destitution. Revisiting the film via its props, The Still Living End translates Araki, offering us an opportunity to see how the demands and needs of memory, as they pertain to the crisis, contend with memory’s own failures.

Vincent Chevalier,

À Vancouver (still), 2016. Video. 34 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Vincent Chevalier,

À Vancouver (still), 2016. Video. 34 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.