I remember the first time I heard about Nihal Yeğinobalı’s novel Genç Kızlar on a hot summer evening two years ago. I was speaking to a friend about the master’s thesis she had written for her Translation Studies degree at Istanbul’s Boğaziçi University many years before, and her casual mention of this book came as a surprise. Like any reader of novels translated from English to Turkish, I too had come across this prolific translator’s name at some point, but was unaware that she had authored any books herself. Apparently, this novel was relevant to my friend’s thesis as an example of “pseudotranslation,” a concept I’d never heard of before.

A pseudotranslation is a text presented as though it were translated from another language, even though there is no actual original document. As such, it can be regarded as a textual simulacrum that invites a discussion of the circumstances of its making and urges us to ask why an author would feel compelled to pretend there is an original text. There are countless instances of writers, many of them women, hiding their authorship by adopting pseudonyms, but what sorts of conditions would also urge them to claim that they are rendering a text accessible to readers of another language? What credibility is attributed to the non-existent original and its supposed creator that the pseudotranslation wouldn’t possess on its own, and how does this credibility validate the content of the text?

Published for the first time in 1950, the pulp novel Genç Kızlar is the quintessential example of pseudotranslation in Turkish translation studies. It is set in an imaginary performing arts boarding school in the United States called Ludlow Academy and tells the story of Beatrice Karova, Hindley Bell and Mariana Dunne, three young women who all vie for the attention of their handsome teacher Gabriel Samson. Gabriel ultimately falls in love with Beatrice, who is also smitten with him despite her uncooperative nature and all her efforts to hide her sentiments. (It would be fitting to use the Turkish word hırçın to describe Beatrice’s temperament in the novel, but I struggle to find a satisfying translation.) The two lovers ultimately have a secret affair and furtively meet in various locations around the school. We read the titillating details of their trysts, such as the moonlit night when Beatrice performs the first oral sex of her life on Gabriel. But as pleasurable as it is to read about their passionate relationship, what makes the novel so fascinating as an object of scholarly study is not really its plot. It’s the story of how it came to exist as a text, and the socio-political implications of its reception by Turkish readers.

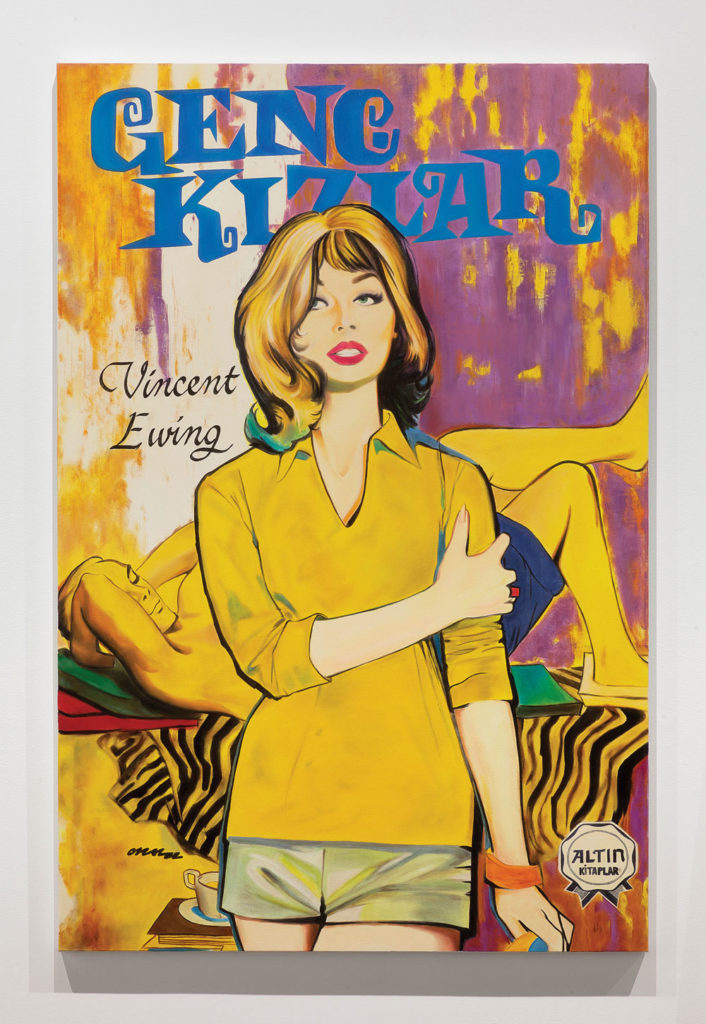

The original cover of Genç Kızlar painted by Cindy Esteves as part of Erdem Taşdelen's project The Curtain Sweeps Down, 2018. Photo: Michel Brunelle.

The original cover of Genç Kızlar painted by Cindy Esteves as part of Erdem Taşdelen's project The Curtain Sweeps Down, 2018. Photo: Michel Brunelle.

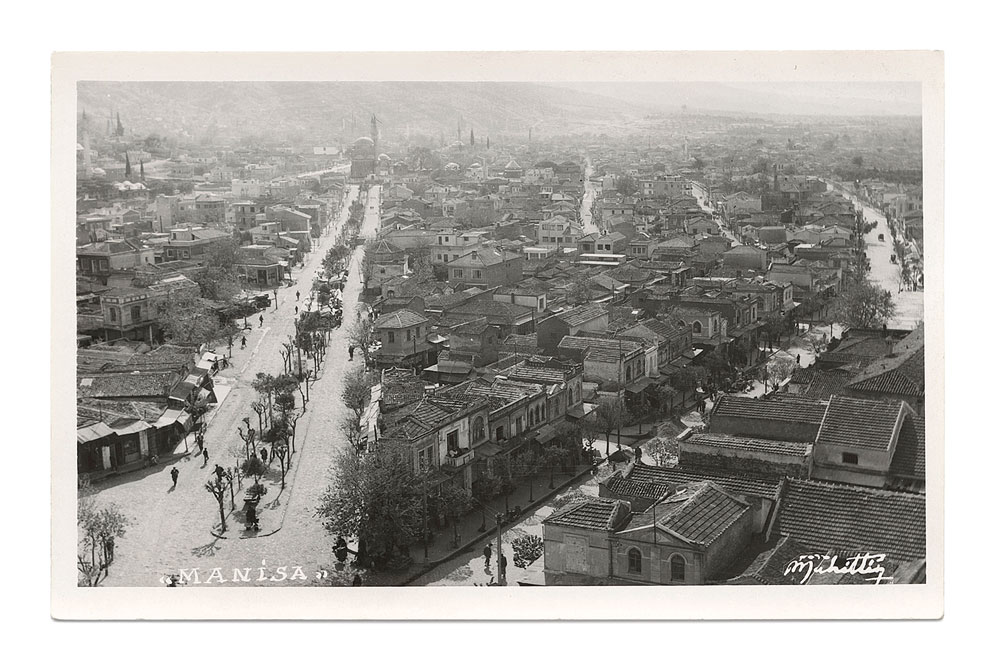

Found image of the city of Manisa, where Yeğinobalı wrote her novel, Genç Kızlar. Part of Erdem Taşdelen's project The Curtain Sweeps Down, 2018. Photo: Michel Brunelle.

Found image of the city of Manisa, where Yeğinobalı wrote her novel, Genç Kızlar. Part of Erdem Taşdelen's project The Curtain Sweeps Down, 2018. Photo: Michel Brunelle.