The 1983 hour-long TV special Don’t Eat the Pictures: Sesame Street at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was a favourite of mine and my brother’s in the early ’90s. In it, the Sesame Street gang gets locked in the museum overnight looking for a lost Big Bird. The relevant character here is Cookie Monster, who clutches a “food art” brochure as he peruses the bevy of food-themed still-life paintings on display at the Met, having to be physically restrained from eating Cezanne’s Still Life with Apples and Pears (circa 1891–92).

After decades of dormancy, the phrase “don’t eat the pictures” popped back into my mind while scrolling through Stephanie Temma Hier’s work on her website. Meticulous figurative paintings, many of which feature scenes of fruit and other consumables, nestle within whimsical hand-built ceramic frames. We see winding snakes encircle a painting of ruby-red fruits in More for routine than result (2020); Cheeto-orange gunk surrounds manicured hands pinching shellfish in Wonderful for other people (2020); twig-like bones frame a school of purple fish fighting against a net in Did you let them skim the cream off (2019). The frames, ceramic sculptures in their own right, act as vessels for the sumptuous imagery, like bizarro versions of fruit bowls.

Unlike those painters whose precise depictions of fruit at the Met were just realistic enough to trick the cookie-crazed character into taking a bite, Hier chooses to break the illusions of the classical painting techniques she’s mastered. In addition to amplifying the presence of the frame—typically standardized and distinctly separate from the “art”—Hier highlights the surface of the canvas with decidedly un-classical adornments like temporary tattoos, goofy cartoon drawings or ceramic baubles. With this, Hier launches her work into the contemporary moment, disrupting the smooth realism of traditional canonical painting styles with internet-age motifs.

Stephanie Temma Hier, Did you let them skim the cream off, 2019. Oil on canvas with glazed stoneware frame, 14 x 12 x 3.5 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.

Stephanie Temma Hier, Did you let them skim the cream off, 2019. Oil on canvas with glazed stoneware frame, 14 x 12 x 3.5 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.

“I’m interested in taking images out of their original context and bringing them into the lexicon of my work,” Hier said during a Skype conversation from her Brooklyn-based studio. “For me it’s about creating a non-hierarchical space for all of these images to coexist.” The Toronto-born artist is clearly a collector: of disparate imagery, historical references, words and phrases that make up her riddle-like titles, and techniques and materials. Working mostly from found images, Hier mines the internet for content, but fixes the ephemeral stream of fleeting digital imagery into slow, handwrought processes and tangible materials.

And her process is slow. Creating the sculptural elements alone takes close to a month, with three-week drying periods and multiple 12-hour firings. Only then does the meticulous process of oil painting begin (on custom stretchers also made by Hier). Her twofold process is certainly a balm to the exhausting hyper-speed of digital connectivity, and is emblematic of a broader turn back to craft within contemporary art (just look at the massive survey exhibition “Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019” currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, for one). “I think it’s all a reaction to how increasingly alien and digital things are,” Hier observes.

As a nostalgic print devotee and low-key Luddite, I fall easily for analog art processes. But Hier’s work also piqued my interest because of its unique placement among other painters of her general demographic. (“Not many twentysomethings are doing figurative painting right now,” I recall saying to her during our conversation.) Her work contrasts more abstract trends seen lately, where raw impressionism is born from the deliberate eschewal of representative accuracy. I’m thinking of geetha thurairajah’s vibrant airbrushed strokes, Katie Lyle’s blended pastels or Brook Hsu’s fluorescent abstracts and fantastical creatures, all artists Hier shared a group show with at Sibling gallery last year.

Hier channels the spirit and spunk of her contemporaries, but does so with the precision of a 17th-century Dutch still-life painter. Having trained since the age of 11 in figurative painting at the Academy of Art Canada in Toronto and studied animation throughout high school, Hier had already honed her technical skills before completing a BFA in painting at OCAD University in 2014. Homages to her classical training reverberate throughout her work in both content and technique.

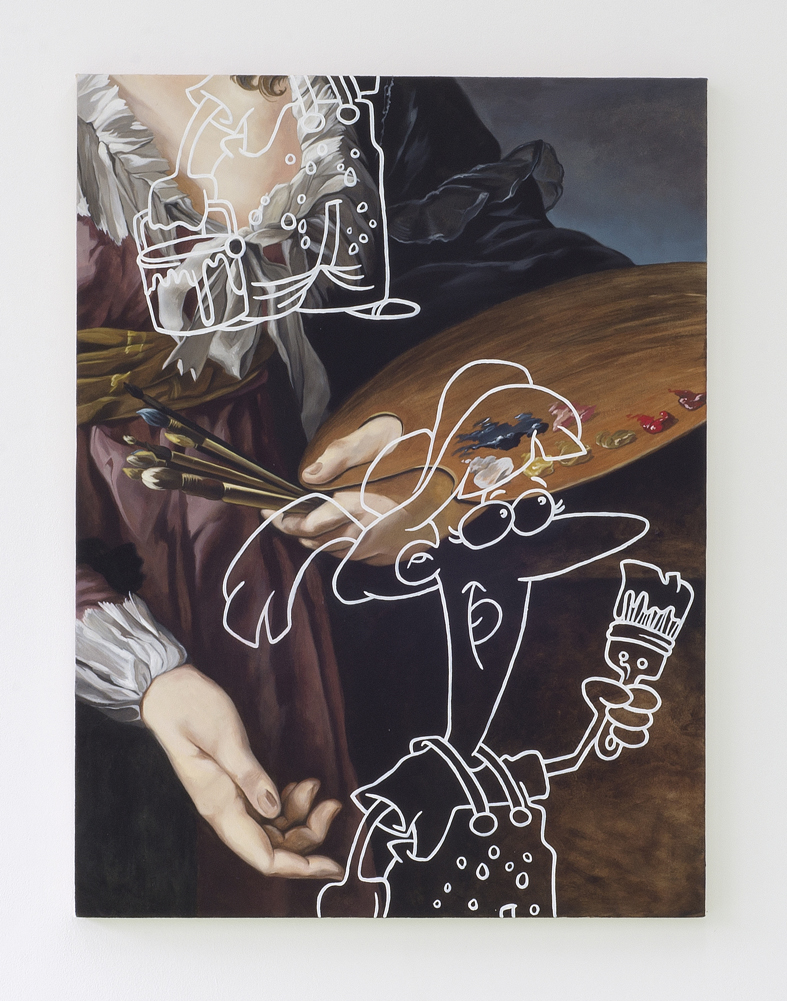

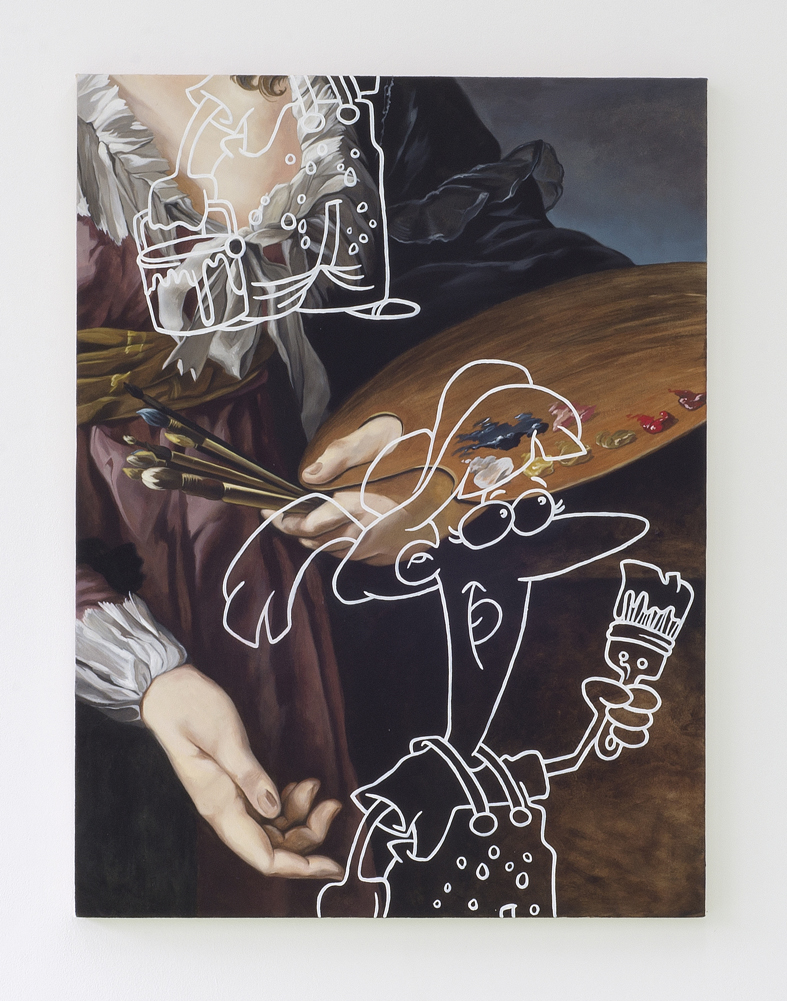

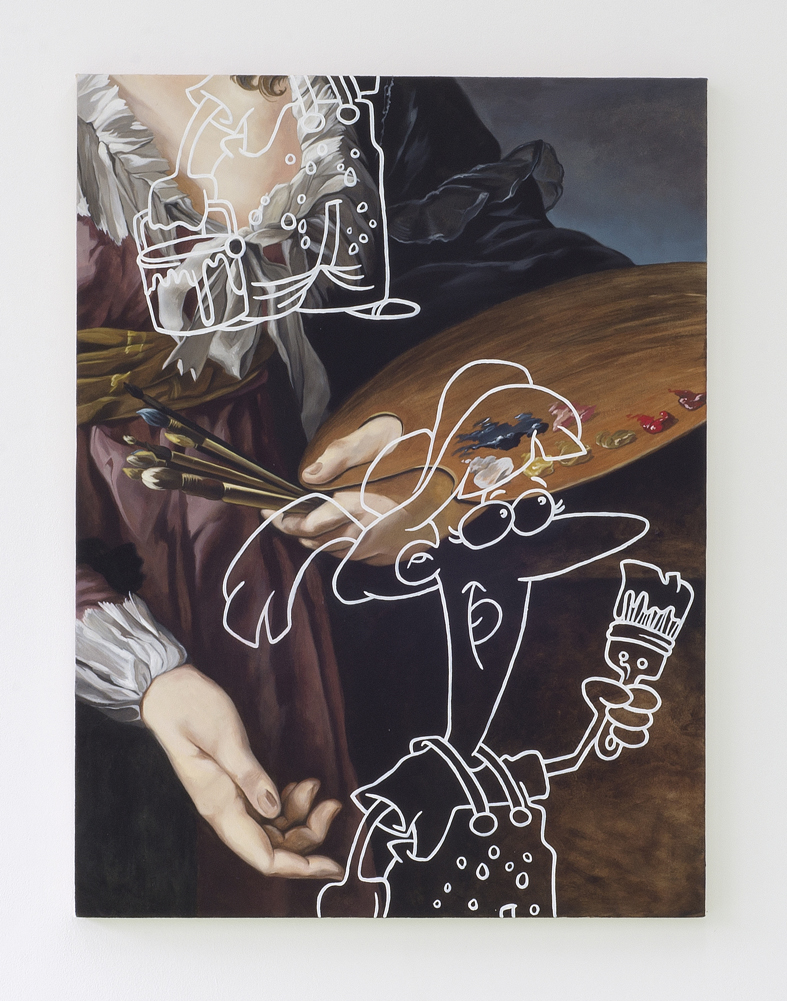

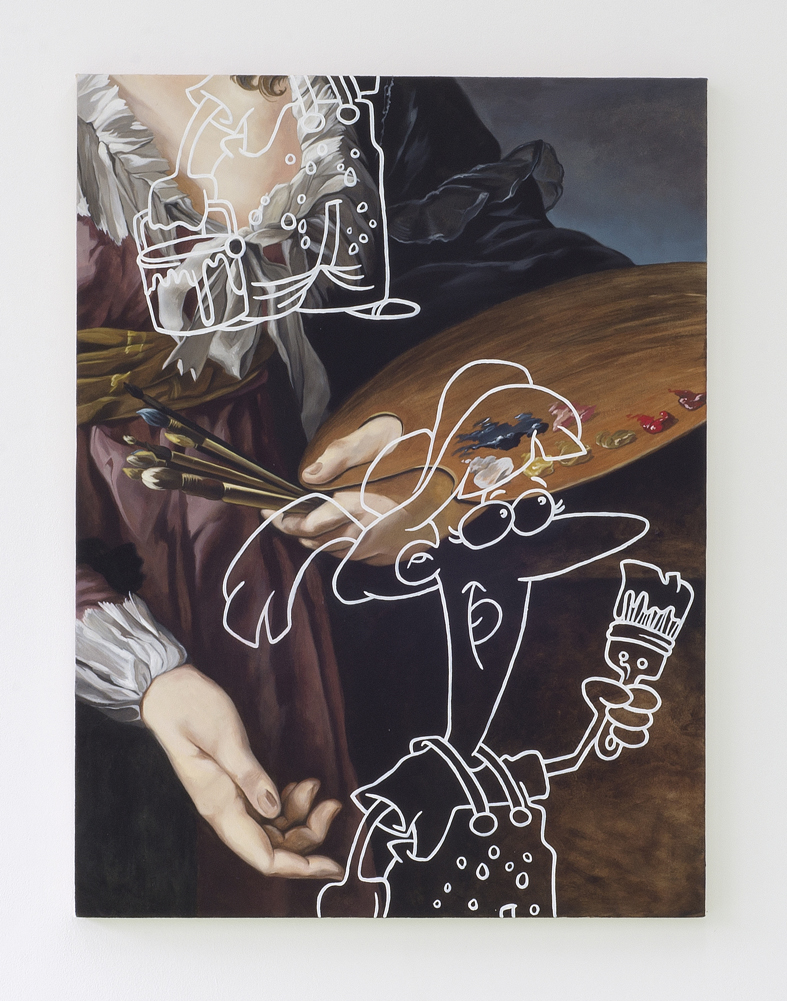

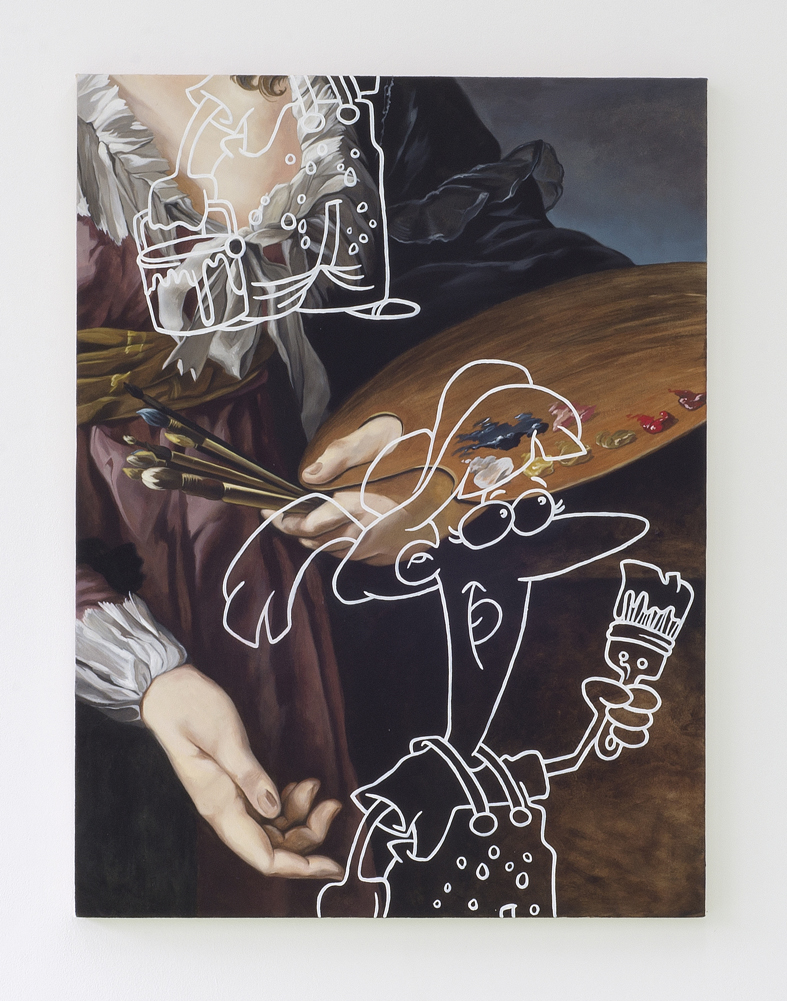

In 2018 Hier had a solo exhibition titled “Walnuts And Pears You Plant For Your Heirs,” presented at David Dale Gallery in Glasgow. The show was emblematic of Hier’s love of early animation and its myriad characters, reprising 1950s and ’60s animation styles à la Preston Blair or Walter Lantz. In many pieces, we see a classic figurative still-life painting but with a cheeky flair: line drawings of cartoon characters or temporary tattoos sit directly on top of the classical scenes, often with references to the process of painting itself. In Walnuts And Pears You Plant For Your Heirs (2018), a glowing, dewy melon is obscured by a four-fingered cartoon hand giving a (sarcastic?) thumbs up. Ceramic brushes and tubes of paint line the frame, almost as if saying, “Look! I passed my figurative painting class.” In With A Belly Full Of The Classics (2018), the same white-outline technique is used to foreground a jaunty-capped caricature of a painter over a Vermeerian view of a woman’s torso in period garb holding a painting palette.

On one hand, these pieces display a reverence for the skill and meticulous precision of the Dutch Golden Age of painting—one that influences our aesthetic tastes to this day—but on the other, they could be seen as a playful flipping of the bird to the monolithic worshipping of the European canon. In all cases, Hier’s interventions immediately deflate the loftiness often associated with canonical work, presenting the characters of traditional, Eurocentric classical painting as just more loony tunes in the cartoonishly singular history of Western art.

Stephanie Temma Hier, With A Belly Full Of The Classics, 2018. Oil on canvas. 48 x 36 in. Courtesy the artist/David Dale Gallery, Glasgow.

Stephanie Temma Hier, Walnuts And Pears You Plant For Your Heirs, 2018. Oil on canvas with glazed stoneware frame. 13 x 10 in. Courtesy the artist/David Dale Gallery, Glasgow.

Stephanie Temma Hier, “Walnuts And Pears You Plant For Your Heirs” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist/David Dale Gallery, Glasgow.

Stephanie Temma Hier, “Walnuts And Pears You Plant For Your Heirs” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist/David Dale Gallery, Glasgow.

Stephanie Temma Hier, “Walnuts And Pears You Plant For Your Heirs” (installation view), 2018. Courtesy the artist/David Dale Gallery, Glasgow.

But maybe that’s too clean of a takeaway; Hier deliberately likes to “throw a wrench in the narrative” with confounding titles and bizarre juxtapositions. The assemblage of references seems to be the crux of her practice, as it forces a collision between seemingly distinct timelines. “One way I’ve spoken about my work is in terms of speed, and the speed at which we consume and view [images]. Thinking about the internet, which is so fast, and older cartoons, which are so slow, it’s kind of this collapse of time where things from any era or any period can exist now, and very much be from and about today,” Hier reflects. I imagine briefly what Rembrandt’s Instagram would look like.

Though Hier has participated in numerous group shows in Canada and was a national finalist in the RBC Canadian Painting Competition in both 2016 and 2018, her upcoming show at Franz Kaka in Toronto marks her first major solo exhibition in Canada. In it, Hier continues to play with themes of consumption. In Green grass finely shorn (2020), cabbage in a bed of soil sits within a frame of ceramic snails and snakes, glazed in a complimentary sage green. In Spring now comes unheralded (2020), ceramic toadstool mushrooms and fungi sprout from the sides of a painting of chickens. “For this [exhibition], the imagery is all connecting back to the food production process and consumption. There’s imagery of the fishing industry, or the feedlot, or farming. There are images of abundance and produce…it’s this process that exists in different stages, the same way that my work does.”

Existing in different stages is a good way to put it. Stages can refer to steps within a process, periods of growth, different eras in a society’s development, geologic strata of time and of course sites for performance. From the clay Hier uses to sculpt her elaborate frame-sculptures, drawn from the earth and its layers of sediment, to the visual layers of references she culls from the internet, she excavates aesthetic matter from all manner of “stages,” forcing the performance of cultural mediation into vivid relief. In so doing, she wryly reframes imagery common to museums’ hallowed halls, poking fun at the historically validated visual lexicon of Western art. Her work is a reminder that no image, context or framework exists in a vacuum—that we should avoid consuming images uncritically. Or, as Cookie Monster might put it: don’t eat the pictures.

Stephanie Temma Hier, Green grass finely shorn, 2020. Oil on linen with glazed stoneware sculpture 30 x 26 x 6 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.

Stephanie Temma Hier, More for routine than result, 2020. Oil on linen with glazed stoneware sculpture. 21 x 17.5 x 4 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.

Stephanie Temma Hier, Spring now comes unheralded, 2020. Oil on linen with glazed stoneware sculpture, 20 x 16 x 3 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.

Stephanie Temma Hier, But a childish toy, 2020. Oil and ceramic on canvas with glazed stoneware sculpture, 14 x 11 x 2 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.

Stephanie Temma Hier, When seagulls follow a trawler, 2020. Oil on linen with glazed stoneware sculpture, 29 x 24 x 4 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.

Stephanie Temma Hier, Wonderful for other people, 2020. Oil on linen with glazed stoneware sculpture. 20 x 17 x 2.5 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.

Stephanie Temma Hier, Wonderful for other people, 2020. Oil on linen with glazed stoneware sculpture. 20 x 17 x 2.5 in. Courtesy the artist/Franz Kaka.