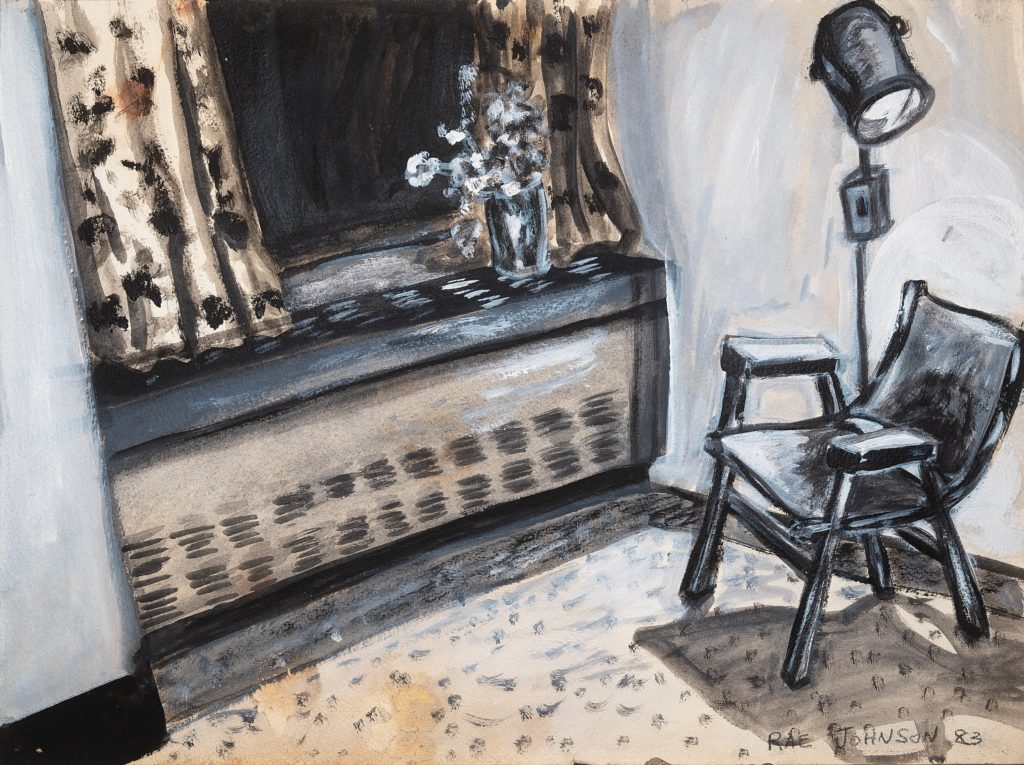

In 1983, Toronto painter Rae Johnson, then aged 29, was hospitalized with a viral form of arthritis from which there was no certainty she would recover. She could not walk. Though her ability to use her hands was limited, she made a series of gouache paintings from her hospital bed: of social settings and empty rooms, some of them visited by angels. One drawing renders a chair, a radiator, a lamp and a window in a kind of lonely if unremarkable institutional setting; another pictures two figures, dimly lit, oblivious to the presence of an angelic spectre. Angels haunt these images as death haunted Johnson in the hospital. In the present, one year into the coronavirus pandemic, as mass illness and death puts images of hospitals into circulation daily, Johnson’s drawings are painful and familiar. Johnson passed away in May of last year, then aged 67, her death unrelated to the virus. In a year of inestimable loss, hers is deeply felt.

At the time of her death, an exhibition of Johnson’s paintings was viewable by appointment at Christopher Cutts Gallery in Toronto, the first of two exhibitions intended to provide a survey of her 40-year career. At its centre was a monumental canvas, Angels in the Palace (1983), which stands more than two metres tall. In it, a red surface is set off from darkness by a colonnade at its periphery. A bathing figure lies in a pool of blue, with a standing figure at its side. In the foreground, an angel appears, so identified by feathered wings. The focal centre of the painting lies between the two upright figures: a tenuous, gossamer beam of white light that forms an arched conduit between their outstretched arms. When, in 1983, Johnson returned home from the hospital, she continued to work with angels, borrowing imagery, in this case, from a dream she had had the year before. In the dream, a woman had been simultaneously lying in a bath and standing, reaching out to an angel. She wrote that “the angel was trying to save the woman from herself.” She also wrote that the woman was her.

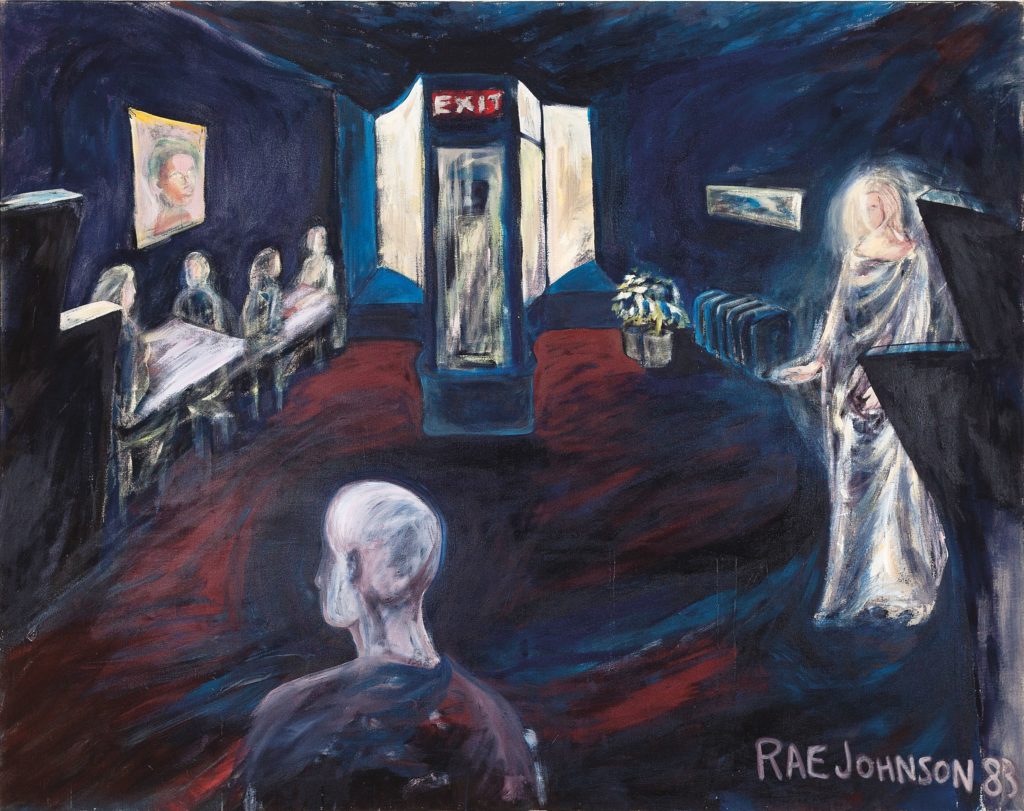

Angels in the Palace is recognizable as a secular, stylized vision of the Annunciation: in some kind of arcade or architectural enclosure, an angel intervenes in the life of a woman. Whereas Renaissance renderings show the archangel Gabriel claiming Mary’s body as a vehicle for history and God, Johnson’s angel recovers the woman’s body from and for herself. This painting was one of a series Johnson executed in the wake of her stay at the hospital (and that would be exhibited at 49th Parallel gallery in New York later that year) that picture angelic visitation across a variety of settings. Angel in the Rivoli (1983), for example, excises Johnson’s angel from its dreamscape and places it, more delicate and more spectral, in the world of the living. It’s a bar scene, and the angel is attractive in its unlikeliness. The bars of Queen Street West in Toronto were regularly the subject of Johnson’s paintings, and many of these paintings look like how alcohol can feel—lonely, soporific, clouded, blue. (Johnson’s 1984 painting Night Games at the Paradise, a paragon of this style, was recently acquired by the Art Gallery of Ontario. It’s the only work of Johnson’s in the collection.) In Angel in the Rivoli, the angel’s presence in the bar acts as a glowing conduit between myth and the social, and between grace and abjection.

Rae Johnson, Angel in the Rivoli, 1983. Acrylic on canvas, 1.68 x 2.13 m. Courtesy Christopher Cutts Gallery.

Rae Johnson, Angel in the Rivoli, 1983. Acrylic on canvas, 1.68 x 2.13 m. Courtesy Christopher Cutts Gallery.

In the making of these paintings Johnson drew as much on Renaissance imagery—also a frequent reference in the work of her close friend and interlocutor, Toronto painter Sybil Goldstein—as on the work of Carl Jung, in whose psychoanalytic theory archetypes are a passage by which visual phenomena might translate to universal truth. Here, as anywhere, one ought to be suspicious of any concept of the universal—suspicious of how inherited ideas can organize facts into untruths, can distort or misrepresent the real, can fix images into patterns that occlude or do harm. This violence isn’t absent from Johnson’s canvases, but neither is the power of the angel to conjure beauty, light and beneficence. An angel is a platitude. Using a symbol of this order, so overfamiliar in visual culture, invariably flirts with bad taste. I imagine Johnson deploying these angels to test taste’s elasticity. How far can a sign be stretched into banality and still hold weight?

An angel is a platitude. Using a symbol of this order, so overfamiliar in visual culture, invariably flirts with bad taste. I imagine Johnson deploying these angels to test taste’s elasticity. How far can a sign be stretched into banality and still hold weight?

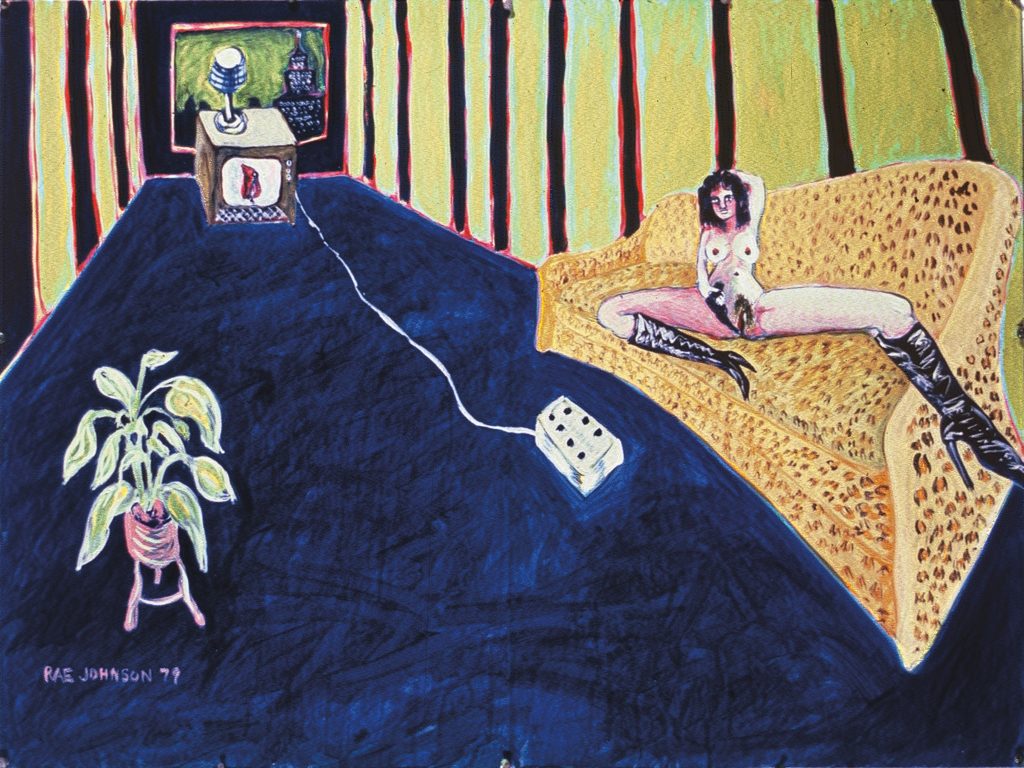

Bad taste is an accusation that has attended Johnson’s career since the very beginning. Paintings she contributed, as a graduating student, to an open-house exhibition at the Ontario College of Art in the spring of 1980 were the subject of public complaints, prompting negotiations between the Toronto police and the school over their removal. The offending paintings constituted part of a series Johnson undertook in 1979 where each painting stages nude bodies, mostly women’s, in sparsely furnished, technicolour rooms. Formally repetitive, the paintings look to pornography as a site for the complicated meeting of sex, power and the mediated image. Some works from the series portray technologies of image capture and circulation—both existing and legible ones, such as a television set in Empire State (1979), as well as speculative mechanical objects, such as a headset that connects, with twin wires, the eyes of a clothed observer to a small rectangular device in Woman and Man with Machine Eyes (1979). Others insert some kind of flat image inside the diegetic world of the painting—a mirror or framed picture on a wall—signalling the intimacies of power and powerlessness in looking and being seen.

Johnson’s rooms traffic in alienation, nudity and abjection—a negative vision of sex work informed, at least in part, by Johnson’s own brief experience as a pornographic model. This series evidences early hallmarks of Johnson’s style: slippery, hysterical interiors; spectacles of sex, sociality and psychodrama; and the blending of physical and psychic realities. Distortion sweeps the surface of the image with vertigo. Even as these paintings take the camera’s capture and reproduction of images of women as their subject, visually they have little in common with its ways of looking: there’s no neat dimensionality, no flatness, no causal relationship between shadow and light. At OCA, the exhibition was ultimately allowed to remain open with Johnson’s work on view on the condition that the school install signage urging parental guidance. (In considering the political climate in which this intervention occurred, it seems instructive to recall that the following year, in 1981, the “morality squad”—the same branch of the Toronto police Johnson describes as having threatened to close the open-house exhibition—executed Toronto’s notorious Operation Soap bathhouse raid, whose 40-year anniversary was marked this February. It was one of a series of police raids on local gay bathhouses that also saw Andy Fabo, Johnson’s close friend and future collaborator, placed under arrest in 1978.)

Rae Johnson, Untitled #3, 1983. Gouache on watercolour paper, 38.1 x 50.8 cm.

Rae Johnson, Untitled #3, 1983. Gouache on watercolour paper, 38.1 x 50.8 cm.

Rae Johnson, Empire State, 1979. Acrylic on paper, 43 x 56 cm.

Rae Johnson, Empire State, 1979. Acrylic on paper, 43 x 56 cm.

The morality squad was one element that judged Johnson’s figuration to be in poor taste; others were to be found in the Toronto art world of the 1980s, where Johnson, alongside a peer group of friends and collaborators, would briefly emerge as a controversial champion of a return to figuration in art. The year following her graduation, Johnson was among a group of artists—Oliver Girling, Brian Burnett, Andy Fabo, Sybil Goldstein, Tony Wilson, Stephen Niblock and Hans Peter Marti (though Niblock and Burnett would leave the group the following year)—who would open a collectively run gallery called ChromaZone.

In these artists’ practices, work and life indexed each other: they ran the gallery out of Girling’s Spadina Avenue walk-up apartment and populated its exhibitions with portraits of friends and lovers, images of Toronto’s downtown, and select international works that could be transported to the city in a suitcase. The inaugural exhibition, “Mondo Chroma,” was framed as “images of the working life: office, construction-site, classroom, club; the sporting life; rock and roll, sex, astronauts; the domestic life; and the daily life of artists.” It included Johnson’s Anima, Animus (1981), in which a bed hosts a seated, nude woman and a man “wrapped in an embryonic membrane,” per Johnson. In the room with them is a modest Madonna figure, draped in white. This is the Madonna’s first appearance in Johnson’s canvases, where she would, over the following years, become a regular visitor, especially to scenes of technological mediation and immodest behaviour.

ChromaZone engendered both an energetic reception and critical antipathy—the latter perhaps for its members’ youth and irreverence, or because of the perception that their project was an anti-intellectual one. This impression is not mitigated by the provocative rhetoric that surfaced in contemporary discussions of ChromaZone’s work, in which figurative painting was seen as an answer to the excessive abstractions of conceptualism, and celebrated as an unmannered transcription of the real. These analyses give way to ideas so conservative that 40 years seems not long enough ago for critics to have had them, especially the notion that painting has a privileged relationship to truth. But I do think of painting, and Johnson’s painting in particular, as having a privileged relationship to time, with each mark on the painting’s surface evidencing the work of a body as it travels through time.

Rae Johnson, Angels in the Oranien Bar, 1983. Acrylic on canvas, 1.9 x 2 m. Courtesy Christopher Cutts Gallery.

Rae Johnson, Angels in the Oranien Bar, 1983. Acrylic on canvas, 1.9 x 2 m. Courtesy Christopher Cutts Gallery.

It’s the work of that body, Johnson’s, that endures in the year of her death, which has also been the year of the pandemic. It’s a period in which, at least for me, time’s measurements have never felt so untethered from the experience of its passage. A year seems inadequate as a measure of all that’s happened, a container that can’t hold such catastrophic loss. I think of Angels in the Palace as an alternative way of cataloguing a body’s passage through time: Johnson dreaming; Johnson becoming ill and then better; Johnson’s brushstrokes recording the movements of her body; and, many years later, Johnson’s passing from the world of the living to the eternal realm of her angels on the picture plane.

Though Johnson would move on from painting angels by the end of 1983, and from painting figures almost altogether by the end of the 1980s, an angel appears in one of her most recent paintings, Winter Angel (2018), of which she writes: “I was becoming ill. It was one of my last paintings. I was diagnosed with ALS in August 2019. I think I had an unconscious knowledge that the series was a return to my earlier work. It had come full circle. The angel turns away from the central figure, who is walking down a city street. It is cold and desolate. The angel leaves. The story is over.”

Winter Angel bears the formal hallmarks of Johnson’s mature work: thin and consistent figures, delicate brushstrokes, rooms and outdoor spaces no longer washy from distortion. Here the sacred and the profane are not rendered in opposition, nor in extremes of dark and light. Instead they look harmonious, like slight variations on similar forms. There’s little conflict. The story is over. And yet the drama of Johnson’s earlier canvases survives her in its consonance with this moment in history, defined by both dullness and cataclysm. As symbols for grace and beauty her angels are both too familiar and too powerful, which feels like it rhymes with the experience of living through the pandemic and feeling the simultaneity of the banal and the eternal, the enormous, the unbearable.

Rae Johnson, Angels in the Palace, 1983. Acrylic on canvas, 2.15 x 1.69 m. Courtesy Christopher Cutts Gallery.

Rae Johnson, Angels in the Palace, 1983. Acrylic on canvas, 2.15 x 1.69 m. Courtesy Christopher Cutts Gallery.