When I met with Ryan Rice and Skawennati to talk about Nation to Nation, an Indigenous art collective they formed with Eric Robertson in 1994, it felt fitting that we gathered together at Skawennati’s house not far from the Montreal building (now the Nordelec Condos, in Pointe-Sainte-Charles) where Nation to Nation held the first installation of their landmark “Native Love” exhibition in 1995.

Skawennati and Rice shared an apartment nearby on McGill Street in the mid-1990s, but this was before “anyone even knew where Old Montreal was,” Skawennati told me, Old Montreal before it became all upscale eateries, condos and boutiques. “Native Love” came only a few years after the 350th anniversary of Montreal in 1992. This milestone in Quebec’s colonial history not only marked a moment of rapid economic growth for the city, but also a period of overwhelming gentrification. The big question on the minds of the generation of artists and cultural thinkers who were being pushed out of their bohemian Montreal artist ghettos was, as Rice recalled: “What’s next?”

Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew predicted the importance of Nation to Nation in a 1996 piece on “Native Love” for FUSE, calling the exhibition “the child of a new generation.” There was a divide at the time between older generations of Indigenous artists, defined by the Society of Canadian Artists of Native Ancestry (SCANA), and younger generations who sought to carve out a space for themselves within Indigenous art. Skawennati and Rice remembered piling into Rice’s car—without a map—sure that they would eventually make it to Halifax where SCANA was holding their last conference in 1993. They did make it, only to have their community-based art actions belittled and called “student art” by SCANA artists.

The remnants of SCANA’s crumbling infrastructure were forewarnings to Nation to Nation. The collective rejected the institutionalization and insular infrastructure of SCANA, which they saw as ultimately leading to the organization’s downfall.

“I wasn’t part of any particular artist community and felt very out of touch,” said Rice in a talk written for “Native Love.” “We decided that we shouldn’t and can’t wait for opportunity to be knocking at our doors, because in the real world it was just not happening.” This was a generation of Indigenous artists ready to “force their way in,” as Skawennati put it.

Nation to Nation saw themselves as community organizers who facilitated collaboration between Indigenous artists, and activated their communities through art. The collective began organizing art actions at a time when Indigenous art was just beginning to find its way into the white cubes of contemporary-art galleries.

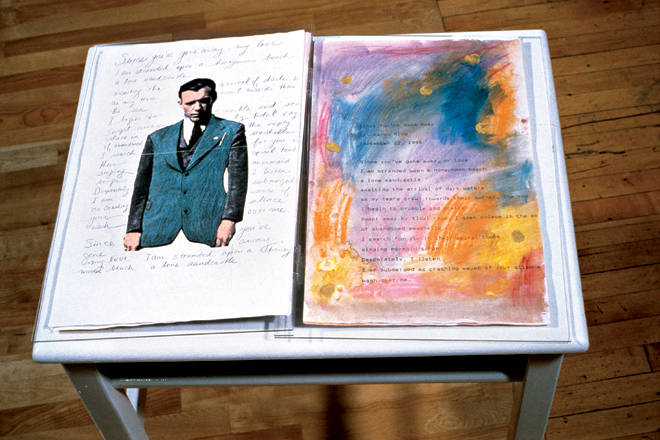

Installation view of George Littlechild and Aaron Rice’s Since You’ve Gone Away (1995) in “Native Love” organized by Nation to Nation in Montreal, 1995. Image courtesy of Ryan Rice.

Installation view of George Littlechild and Aaron Rice’s Since You’ve Gone Away (1995) in “Native Love” organized by Nation to Nation in Montreal, 1995. Image courtesy of Ryan Rice.

Nation to Nation didn’t want to limit themselves to traditional or contemporary methods, preferring instead to subvert that binary by integrating themes like love and sex with traditional practices, and including new media and performance throughout their activations.

“Native Love” came only a few years after the Oka Crisis, at a time when gallerists only wanted artworks about “machine gun, razor wire,” said Rice, and stereotypes about the Mohawk and Haudenosaunee peoples were pervasive. Despite the antagonistic representations of Indigenous peoples that proliferated in the early 1990s, love was in the air. New generations of Indigenous artists and cultural thinkers didn’t want to be at war anymore—they wanted to make love. As Audra Simpson wrote in the exhibition’s accompanying essay, “Making Native Love”:

If we were to trust popular and scholarly representations of Native People we would have to conclude that they, unlike any other peoples in the world, are without love. Native people are represented in mechanistic and ultimately loveless terms: as hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists of yesterday and cultural revivalists of today. They are written in popular press as activists (troublemakers), as artists-with-a-mission, as cigarette smugglers. In new age journals as naturally in tune with the earth, in movies of the seventies as shape-changers. They are Indian Princesses, savage squaws, brave hearted men and guerilla warriors. Rarely however, are they in love (the tragedy of Pocahontas aside), rarely are they contemplating love, acting out of love or simply being, as they are—their Native selves in love or out of love, in the funk out of the funk. How can this be?

Simpson’s writing reads more like a manifesto of love than a catalogue text, and is written with the same sense of urgency and grassroots Indigenous feminist movement building that resonated throughout the exhibition’s DIY foundations. Artists and writers collaborated on artworks in the exhibition, and many participants ended up working with family members—Rice and Skawennati, for example, each pairing with their brothers. The loft used for the inaugural show in Montreal had wall-to-wall windows and no walls—to display the art, organizers improvised with bookshelves that had been left in the space. At sundown, they realized there were no lights and rushed out to buy a dozen desk lamps from Canadian Tire, which would promptly be taken back the next day.

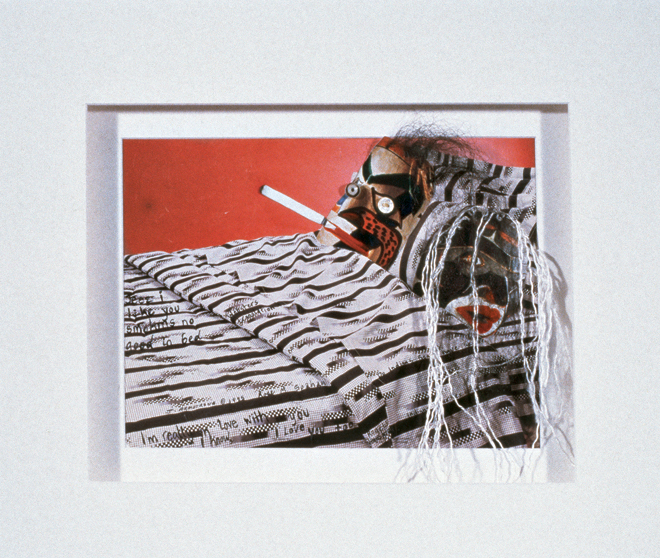

Detail of Rose Saphan and Jeanette Armstrong’s Indians After Sex (1995) in “Native Love” organized by Nation to Nation in Montreal, 1995. Image courtesy of Ryan Rice.

Detail of Rose Saphan and Jeanette Armstrong’s Indians After Sex (1995) in “Native Love” organized by Nation to Nation in Montreal, 1995. Image courtesy of Ryan Rice.

From this modest inaugural event in Montreal, “Native Love” became a series of shows in artist-run centres and galleries across the country. As the exhibition moved, local artists would join the quickly expanding roster, which by its end included George Littlechild, Mary Longman, Paul Chaat Smith, Thirza Cuthand, Ruth Cuthand, Bradlee LaRocque, Lori Blondeau, Shelley Niro, Daniel David Moses and Cheryl L’Hirondelle.

Mary Anne Barkhouse, Florene Belmore and Michael Belmore’s installation Lick, Kill, Frolic (1995) playfully engaged themes from the BDSM community by positioning a set of mirrors opposite a line-up of dog collars: when the viewers looked into the mirrors they became the sub in a puppy-play kink dynamic. In Indians After Sex (1995), Rose Spahan and Jeannette Armstrong contest the disappearing imaginary of the North American Indian at the level of Native sexuality. Two Northwest Coastal–style masks lie in bed together, as one smokes a post-coital cigarette. These masks are far from the inanimate and sterile representations of Indigenous materialities found in museums—they are sexual and agential beings.

Arguably the standout artwork from the show was COSMOSQUAW (1996) by Blondeau and LaRocque. LaRocque, who photographed Blondeau, is well known for the iconic photo taken of him at the Oka Crisis as the camouflage-clad warrior who went face to face with a Canadian military officer. With its tongue-in-cheek portrayal of Blondeau’s hypersexualized body, and correlate stereotypes of Native womanhood, COSMOSQUAW grapples with complex issues of gender, sexuality and representation as played out on Native women’s bodies.

As Indigenous love and kinship become trending theories that academics and writers increasingly squabble over to monopolize, Nation to Nation beckons to us from the past as a capsule of this love imaginary. “Native Love” is an early articulation of Indigenous resurgence enacted through sex, love and care.

Truly before their time, Nation to Nation are hardly credited within the dominant canonization of Indigenous art, and within Indigenous theorizations around love. Indigenous theorists have lost sight of the connections between material life and Indigenous thought, which remains masculinized and vigilantly focused on issues of politics and governance. With “Native Love,” Nation to Nation reminds us that love is much more than theory—it’s a lifeway, animated through our engagements and relationships with one another. After several decades of hearing this call, it’s time we take heed and make Native love, not war.

Lindsay Nixon is Indigenous editor-at-large at Canadian Art.

This post is adapted from an article of the same title that originally appeared in the Summer 2017 print issue of Canadian Art. To get each issue of our magazine delivered to you before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

Lori Blondeau, COSMOSQUAW (detail), 1996. Duratrans in lightbox, 27.9 x 22.8 cm. John Cook Collections. Photo: Bradlee Laroque.

Lori Blondeau, COSMOSQUAW (detail), 1996. Duratrans in lightbox, 27.9 x 22.8 cm. John Cook Collections. Photo: Bradlee Laroque.