The idea of wiping the slate clean reaches new levels in the work of UK artist Michael Landy. For his 2001 piece Break Down, Landy systematically destroyed all his worldly possessions after meticulously cataloguing them. Nearly a decade later, he opened up the same possibility for other artists with Art Bin, a structure in which he invited other creators to discard their works. During a recent residency at London’s National Gallery, Landy created Saints Alive, a series of larger-than-life, self-mutilating sculptures cobbled together from flea-market finds. And in his film H2NY, showing this week at Canadian Art’s own Reel Artists Film Festival, Landy provides his own unique take on Jean Tinguely’s infamous Homage to New York—a kinetic sculpture that met its demise via the New York Fire Department. In this interview, conducted in advance of his Toronto talk and screening, Landy reflects on Tinguely’s influence, the phenomenon of artistic failure and how to really get art audiences to cheer.

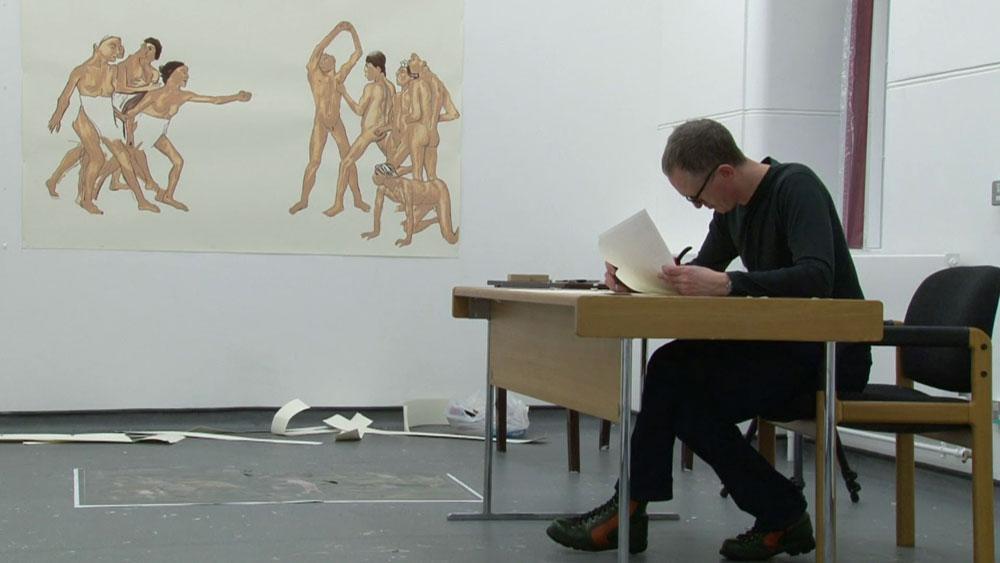

Britt Gallpen: You’ve developed an interesting relationship between construction and destruction in several of your works. For instance, with Break Down, you spent a great deal of time cataloguing your individual possessions, producing a comprehensive database of sorts before systematically destroying each item. Or more recently, with Saints Alive, you built up the works slowly, through notebook sketches, full-scale drawings and finally three-dimensional constructions; but once the sculptures were built, you set up confrontational, and often dangerous, interactions between them. Might you be able to speak to this interplay or binary?

Michael Landy: There’s a sort of temporality about my work. That started, probably, with Market, which I did back in 1990 at Building One, an exhibition space that my contemporaries found. We used to find abandoned buildings and put on exhibitions. So I did this exhibition called Market, which was the scale of a real market with all the usual apparatus of display—but there was nothing actually to show apart from the apparatus itself. All the artificial grass and red oxide and wood was there, but at the same time there was an absence.

Market worked around this idea that nothing is fixed, and everything can be taken apart and put back together again—because a market itself is a very fluid thing, up one day and gone the next. There’s always been that element to my work.

Some of my works don’t continue exist for financial reasons. I destroyed Semi-Detached because it was much cheaper to have it constructed in a way where you couldn’t take it apart and erect it again.

Other artworks have just, you know, disappeared. I’ve gotten to that age when people have started asking me to do a retrospective, and I haven’t really got much left to show—unless I head out to some landfill in Essex and start digging it up, which is what I’ve been thinking about at the moment!

Getting back to Break Down, people would come in and look at what I had and build up some sort of portrait of me as a person and as a consumer. I’ve always thought that piece was taking it all back to where it came from, really, back to its material parts. One becomes aware of how things are constructed by taking them apart. I think that goes from project to project.

With Saints Alive, that was kinetic sculpture, which is always difficult to maintain and is forever breaking down. You know, the National Gallery has a conservation department, but its duties don’t go as far as kinetic art. In some sense, there was this complete lack of communication about how to keep these objects going.

BG: Is that of interest to you when setting up the perimeters of your projects—making them difficult to maintain?

ML: Not necessarily, but it did make me laugh when I read all the correspondence between the staff and the people who are trying to maintain the sculptures. Like, “St. Jerome’s arm has just fallen off and it’s been thrown across the gallery.” There are some really funny stories.

I saw an exhibition by Jean Tinguely back in 1982 at the Tate, when I was 18, and it had a profound effect on me. I was a textiles student at the time. And I saw all these people laughing and smiling in and amongst these kinetic sculptures. Some of them worked and some of them didn’t. But I knew when it came to the National Gallery I wanted to do something that involved the public. Because, apart from the collection, one becomes very aware of the public looking at the artwork. And the museum is free, and it’s right in the middle of the city in Trafalgar Square.

Another factor influencing my work is that I don’t paint, so that has caused me some problems, because painting is a completely different language. My things are kind of temporary monuments, as somebody once said. I always quite liked the idea that they could just get swept away.

I talk about Jean Tinguely because I’ve tried to recreate one of his works in the documentary H2NY. The parallels between that and Break Down are, like, it all ends up in a New Jersey dump or in a landfill in Essex. I liked that Tinguely would talk about these objects as being like life itself, in flux, with things constantly moving and changing. That’s why it was kinetic, in a sense. I like the idea that these kinds of artworks are there one minute and gone the next.

BG: Break Down involved the very personal experience of watching your possessions being destroyed, including those with sentimental value. For Art Bin, this process of destruction and loss was shared among other participants. Was your response different the second, more collaborative, time around?

ML: I’ve called Art Bin a monument to creative failure. Artists are inherently intrigued by their failures.

When Break Down happened, the thing that was picked up in the art world was the destruction of artworks. Yet when I began thinking about destroying all my worldly belongings, it began with me thinking of consumer things like my VCR, my car, my clothes. Then it moved on to more personal things—family heirlooms or photographs or old love letters. Then it moved into my artworks as well, because it was very hard for me to rationalize not.

Another aspect of the reaction to Break Down was that in Britain, you can destroy work, but you can’t always show it in a defamatory way and you can’t change its colour, for instance. But you can destroy it. Which is bizarre.

I was intrigued by that whole debate stemming from Break Down around value, so for Art Bin, I wanted to open it up for everybody, make it democratic. It became a sort of celebration. In a sense, it was like any other bin because after awhile it all looked the same, form-wise—you couldn’t tell what it was anymore. It was like one whole mass.

Obviously, overall, part of my interest has always been rubbish—and what we term rubbish and what things form back into rubbish and why we’ve become so good at throwing things away.

BG: Were you able to hear from other artists about their feelings around ridding themselves of their so-called “failures” in Art Bin?

ML: There were so many different motivations about why people would do it, really. Some people likened it to a sacrifice, so they actually liked the work they did. But there were lots of different reasons. Some artists literally lock their studio doors and they can’t deal with failed projects. There were artists who had gone on to work on other things and then heard about my project and thought that would be a good way to get rid of things.

I mean, I saw Art Bin as a bit of a cathartic experience. At the private view, there were so many people there and everyone had their noses pressed up against the polycarbonate; it was quite primeval. I was a little worried, because it was almost like a public hanging or something. Artists went up the stairs and people would shout and scream as someone would throw their work in.

BG: This notion of failure in art is tricky, as you’ve noted. And a failure to one person might be imperceptible to another. How do you determine if one of your works has failed?

ML: I don’t, really. I would prefer to have, like, one-way glass with a big red sign and big green one to tell me which should go in the bin or not!

BG: To return to Jean Tinguely: in your opinion, was his Homage to New York a failure or not, and why?

ML: No, it wasn’t a failure. People at the time thought it was a failure. But no, it’s not a failure, no. And I haven’t given up in trying to recreate that “failure.” I’m going to have a retrospective exhibition at the Tinguely Museum, so we’ve come 360 degrees now. As you get older it all speeds up; it gets faster. The one thing I really never wanted to do is a retrospective. It’s a big career [milestone] and it’s scary, isn’t it? It’s just horrible. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy!

BG: And outside of this upcoming retrospective, is there anything else you’re working on at the moment?

ML: I’m going to do an Acts of Kindness project [collecting stories from people about acts of kindness they have witnessed in public] in Athens, but I have to think of a new way of doing it from the way I did it on the London Underground. And another Art Bin at the Yokohama Triennale in August. Saints Alive might go to Mexico, but it’s not 100 per cent sure. But those are all old things, and I need to start thinking of some new things.

This interview has been edited and condensed. Michael Landy speaks at the Reel Artists Film Festival in Toronto on Saturday, February 22, at 5:30 p.m. following the screening of the films Michael Landy: Saints Alive, Art Bin and H2NY. Tickets are $8 for students and seniors and $12 for the general public, and the screening and talk takes place at TIFF Bell Lightbox. For more information, visit canadianart.ca/raff.