How public do you want your private self to be? What does it mean to picture softer masculinities in the age of Trump? Why do we privilege happiness over sadness on social media?

These are some of the questions that came to mind for me as I visited with painter Kris Knight in his studio this summer, where he was working on new paintings that will debut this week in a solo booth at Art Toronto.

Over the past decade, this 37-year-old artist, raised in a bunch of small towns in Southern Ontario before heading to OCAD and the big city as a teen, has become known for lush, intimate, romantic paintings of figures both male and androgynous.

These paintings, and their sensibility, have won him renown internationally—including a collaboration with Gucci, a cover of Harper’s Bazaar and a feature in Interview magazine. He now has a dealer in Paris (Galerie Alain Gutharc) and Miami (Spinello Projects) as well as his original one in Toronto (Mulherin, which is doing his solo booth this month).

It’s a significant profile, to be sure.

But as Knight showed me his work in progress on his new series of paintings, I was struck most by his modesty, his shyness (which he happily admits to), and his quiet sense of diligence.

Most of Knight’s paintings are still smaller in dimension, and he tends to paint them while sitting by a window, the canvas propped in his lap. A rolling coffee table in Ikea style holds most of his paints and brushes. His studio in Toronto’s largely non-profit 401 Richmond building is shared with another artist. He comes to the studio most every day—and for years, even when he was likely already able to make a living from his art, he still held on to a regular retail shift at a local eyeglass shop.

All this history and process makes Knight, in a way, ideally situated to explore the boundaries between private and public, interior and exterior, image and substance. Knight is attuned to a range of experience: from the performance of everyday-life roles like customer and client, to being sensitive to the ways gender is portrayed, to holding an awareness of how artists are expected to market themselves online.

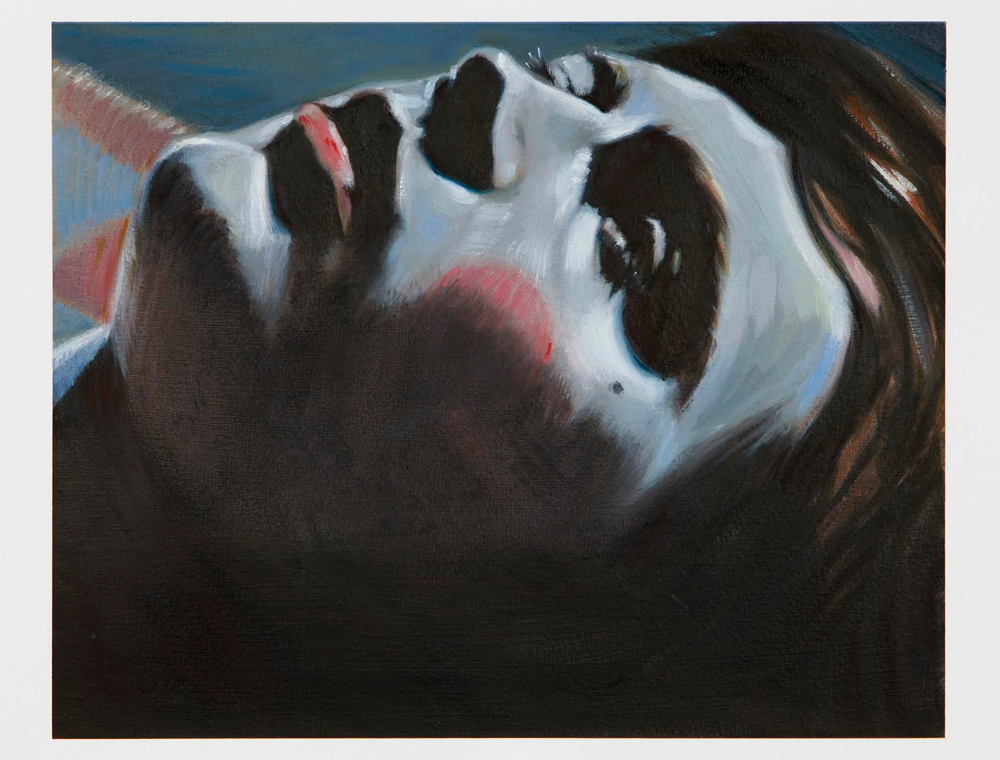

“The whole series is about performance,” he says of the new work headed to Art Toronto, “but using a theatrical dimension as a prism to find out what is real…what’s faked and what’s staged.”

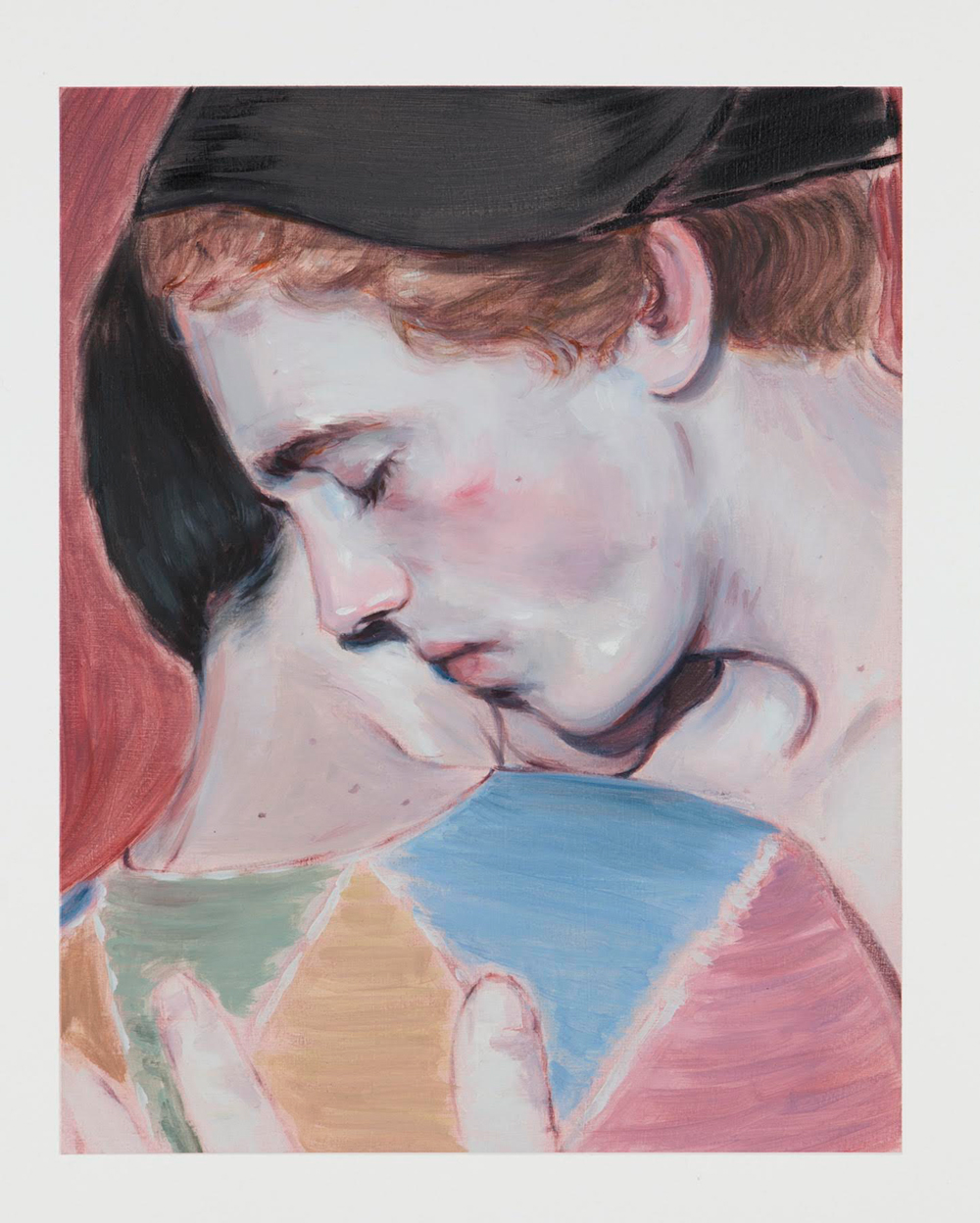

Kris Knight, The Embrace, 2017. Oil on prepared cotton paper, 14 x 11 inches.

Kris Knight, The Embrace, 2017. Oil on prepared cotton paper, 14 x 11 inches.

Many of the works in Knight’s solo booth at Art Toronto were started this spring while he was in residency at Maison d’Art Bernard-Anthonioz in Nogent-sur-Marne, France.

The MABA house, as it’s called is where one of Knight’s favourite artists, Antoine Watteau, died in 1721 at the age of 37. (Somewhat uncannily, Knight himself turned 37 during his stay there.)

Though Watteau lived centuries ago, Knight feels a link to him, one both painterly and personal.

Many of Watteau’s paintings focused on performance and performers, for instance—like actors from the Italian commedia.

“His work had to deal with performance, because he was really introverted and shy, like me,” Knight says. “I’m drawn to the class clown, or someone who has so much confidence that they could command a room. I’m an observer; I like to watch how people act. I’m in awe of that.”

And yet there is also a sense, Knight feels in Watteau’s paintings, of what happens when the spotlight turns off.

“[In] the backstage, he is trying to capture what performers are like without the audience,” says Knight. “That’s the thread of the show—how do these people who crave attention act without an audience?”

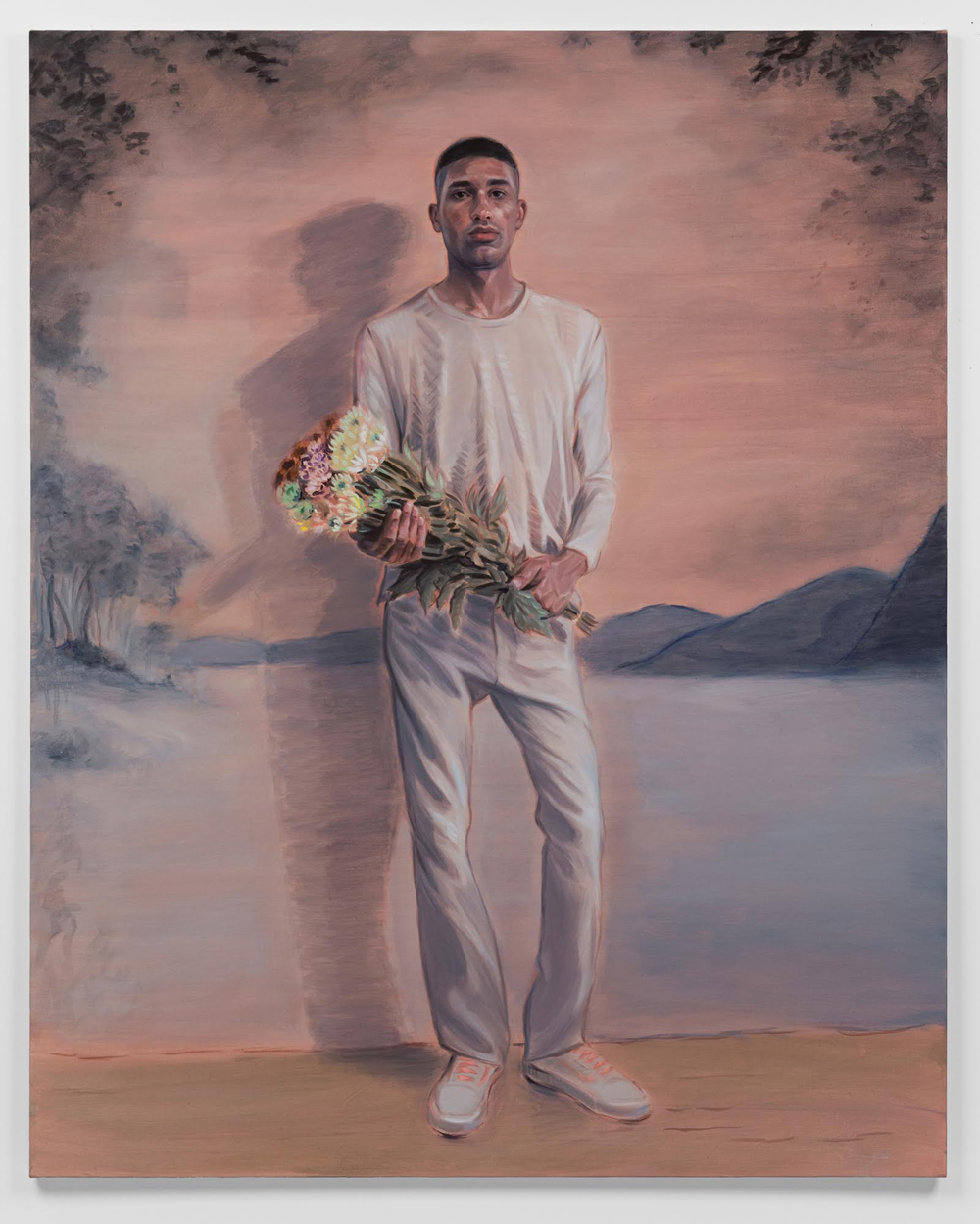

Kris Knight, The Performer, 2016. Oil on canvas, 60 x 48 inches.

Kris Knight, The Performer, 2016. Oil on canvas, 60 x 48 inches.

The questions Knight is intrigued by around performance, audience and the private self is one that is particularly salient in the age of Instagram and other forms of social media.

Of particular concern to Knight in conversation, it seems, is the way that social media, as it exists today, tends to privilege happiness over sadness.

“This idea that on social media that we yell out our successes, but hide our failures” is one thing he mentions.

The emphasis on self-presentation is also sometimes disturbing: “It’s hard to look at an Instagram of someone that’s all smiling selfies and think that they are okay,” Knight says.

We laugh a bit as we remember the proto-social-media platforms of the late 1990s and early 2000s—sites like Diaryland and Livejournal that seemed to favour sharing texts about problems rather than images about perfection.

And Knight himself is self-reflexive enough to know that part of his response to current social-media trends is not just historical, but temperamental.

“I like sad songs. I like paintings that are a little broken. I love the tragic hero,” Knight acknowledges. “I am always skeptical of anything that is too happy.”

What he is aiming for in his work, he says (and that may be missing from our current Instagram moment, I observe) is a balance between moods. It’s a tendency he also admires in the work of his heroes: “With Watteau, his paintings are seen both as joyous and melancholy,” Knight says. “I want there to be a sweetness to my work,” he says—something “authentic” amid the performative.

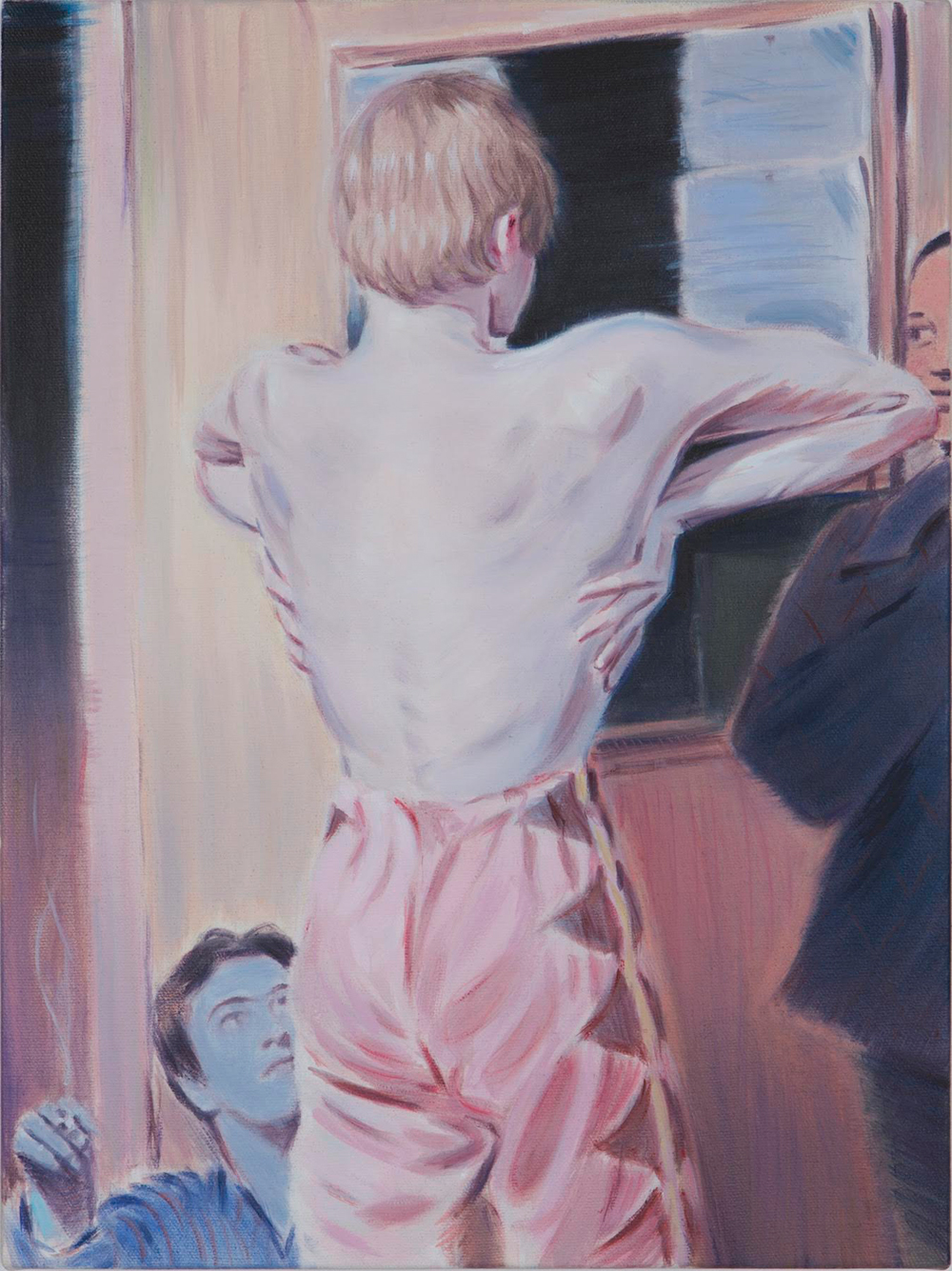

Kris Knight, The Unsuccessful Joke, 2017. Oil on canvas, 16 x 12 inches.

Kris Knight, The Unsuccessful Joke, 2017. Oil on canvas, 16 x 12 inches.

Another way Knight’s decade-long practice might read differently in the current moment, of course, is in the way it articulates gender in the age of Trump. What does it mean to put forward an image of male gentleness, contemplativeness and queerness when the U.S. President’s best-known phrase might just be “Grab them by the pussy”?

“I find everything so hypermasculine,” Knight says of the current mainstream zeitgeist. “Everything just feels so pigheaded….I want to soften my images of masculinity because it’s not something that I see right now.”

Then again, he says the Trump version of manliness is not something new, particularly for a kid growing up in small-town Ontario in the 1980s and 1990s: “As a gay man, I grew up around that kind of stuff,” he notes.

Knight hopes his paintings, which started out in the mid 2000s as being “about androgyny and not really fitting in” can continue to help make space for another mode.

“My paintings are, in a way, an expression of how I’d like men to be accepted,” Knight says. “You can be masculine or feminine, or you don’t have to ‘be’ anything.”

Kris Knight, Elbow Breathing (Your Swollen Pride Assumes Respect), 2017. Oil on canvas, 16 x 12 inches.

Kris Knight, Elbow Breathing (Your Swollen Pride Assumes Respect), 2017. Oil on canvas, 16 x 12 inches.

And while there are lots of big ideas that can cluster to Knight’s work, old and new, the artist is also cognizant of the way his work is personal.

“All of my series of paintings stem from something personal,” says Knight. They address “hiding who you are or kind of staging a kind of false reality”—a familiar theme for many queer people who spent many years in the closet. (Some of the artists Knight is inspired by right now, like the Irish painter Patrick Procktor, long led a double life in that respect, too.)

Knight is also aware of the way performance, staging and the theatre continues to play into many portraiture-based practices, including his own.

“I like figurative painters and portrait painters, who basically can relate their own story by painting other people,” he says, naming John Currin and Kerry James Marshall as among his favourites. “For me, I think of the narrative and then think of how my experiences can be staged into these paintings.”

And yet, beyond the opportunity to stage recurring themes and personae, Knight is also grateful for his practice as a means of working through more recent and troubling realities—be it last year’s Orlando nightclub shooting or his grandmother’s death this spring.

For his most recent Paris show, for instance, Knight painted Last Song, a small oil on canvas of a man, eyes closed, lost in music, dancing in a nightclub.

“Those feelings, where do you put them?” Knight asks. “For me, painting has always been this vehicle for storytelling….It’s a way of getting through stuff.”

Kris Knight’s new work will be on view in Mulherin’s booth at Art Toronto, October 26 to 30.

Kris Knight, Every Time A Little Less, 2017. Oil on prepared cotton paper, 8 x 10 inches.

Kris Knight, Every Time A Little Less, 2017. Oil on prepared cotton paper, 8 x 10 inches.