Since my last column entry, I have received two invitations to attend conferences in Canada dealing with the issue of “safeguarding” Canadian art and culture. One conference in Toronto had as its theme “What makes Canadian art Canadian?” while the other in Edmonton dealt with the question of “Who speaks for Canadian culture?”

Both questions are vexing not because possible answers are elusive (and they are) but because of the presuppositions inherent in the questions. Both perpetuate a logic premised on the binaries of inclusion/exclusion and qualified/unqualified. Such logic reduces complex but legitimate debates about identity and nationality to the essential and fixed. Also problematic is the way that such logic expects deference to those authorized to speak.

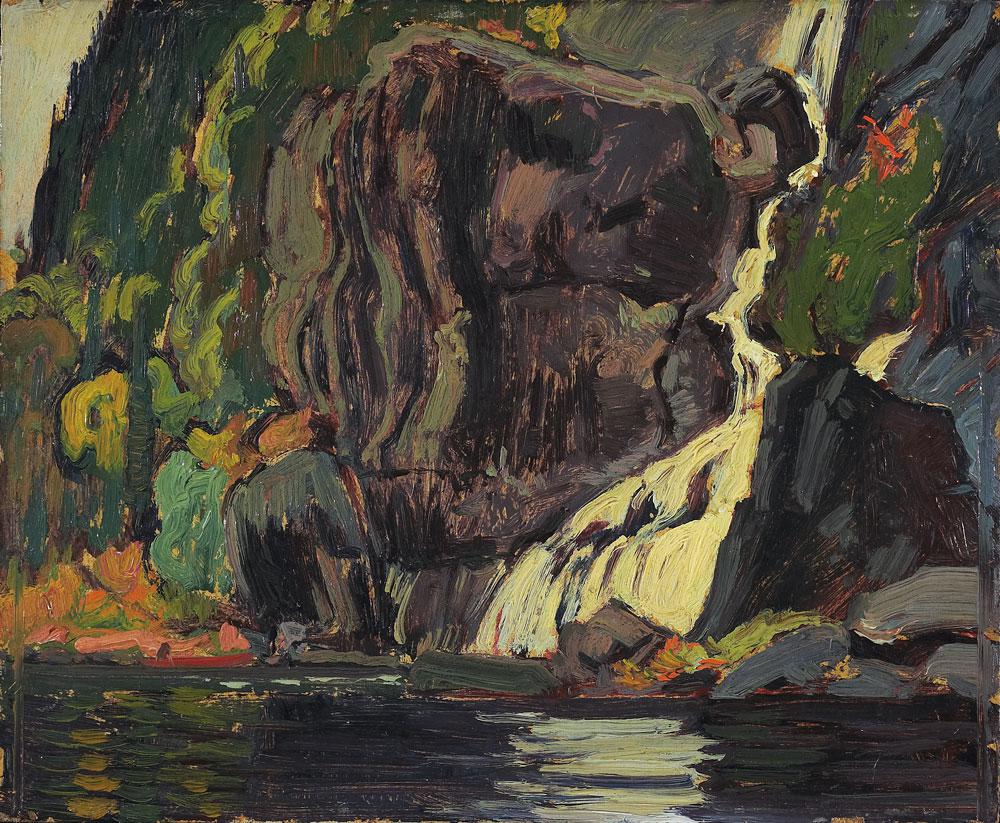

In his conclusion to the 1965 volume Literary History of Canada, Northrop Frye wrote about a Canadian imagination defined by a “garrison mentality.” He was referring specifically to a literature begotten out of a fear of nature embodied by the expansive emptiness of the arboreal ranges and permafrost plains of the Canadian landscape.

Of course, this landscape was never empty, but only deemed so in the service of those who sought to present Canada as an uninhabited terrain at the expense of a First Nations presence both past and present.

To frame Canada as a landscape to be arrived at from afar is to deny those people who were always there. What gets justified in such a framework is precisely the garrison mentality that consists of fortification followed by venturing forth and staking claim to the land. Obviated by the narrative of identity-as-landscape is the pre-existing right of the First Nations to an indisputable claim to the land.

This narrative is complicated by the multi-ethnic and multiracial populations in Canada, whose stories become subsumed into an overarching tale of landscape. The dominance of landscape narratives evens out difference, so that human subjects become something akin to tiny topographical features like a tree, or a hilltop, or a rill, or a crag. The situation also becomes one of exclusion in terms of the disjunctive stories that cannot be contained without a universalizing landscape narrative that cloaks their disruptive voices. Here, landscape is used as a unifying device premised paradoxically enough on exclusion, not so much through racial or religious cohesion (although such factors are significant) but through sameness by relativization (in the form of multiculturalism).

Former governor general Adrienne Clarkson concluded her 1999 installation speech to the Canadian Senate by stating: “I pray that with God’s help, we, as Canadians, will trace with our own lives, what Stan Rogers called ‘one warm line through this land, so wild and savage.’” To equate a sense of national unity with the “wild” and “savage” land illustrates the persistence of the garrison mentality in Canada.

Clarkson made a number of trips to the Far North in her role as governor general. She professed a deep love for the region and its people and transmitted the message that it was there where the “soul” of the nation resides (in spite of the fact that the Far North is itself rife with an alienation wrought by the violent permeations of modernity).

As a Chinese-Canadian, I am particularly interested in how Clarkson negotiated her remarkable biography, arriving in Canada as part of a refugee family from Hong Kong during the uneasy interregnum of civil war in China. I identify with her life story as the son of parents who came to Canada with very little.

My formative experience of Canada was highly urban and racialized, circumscribed to Vancouver’s Chinatown and Strathcona neighbourhoods. Yet the formative impressions of Canada as taught to me in school were about anything but my immediate environment. The majestic mountains of the Rockies, the boundless prairie skies, and the Group of Seven landscape of northern Ontario were far removed from my experiences as a boy growing up in Canada.

While employed as a young man by Via Rail, I encountered for the first time the “warm line through this land.” But it was neither “wild” nor “savage.”

While the landscape was often impressive, it was the people and the often mundane and sometimes sad conditions in which they lived that left a deeper impression. I saw modest makeshift grave markers for Chinese railway workers by the side of the railway tracks on the climb to Jasper. I saw the devastating conditions of reservation life in northern Manitoba. I saw children gathered together and waving to the Via crew as we arrived for a short stop in Hudson Bay, Saskatchewan.

What I saw, to borrow from Trinh T. Minh-ha’s 1982 film Reassemblage, was life looking at me. What I saw was at odds with the official images that confronted me in my mind.

I was not able to attend either conference in the end. I was not permitted to leave the United States due to the restrictions of my visa status at the time. To return to Canada would have jeopardized my right to continue to work at the University of Pennsylvania.

But the questions that the conferences posed have continued to occupy my thoughts here in Philadelphia. I think that asking what makes Canadian art “Canadian” or asking who should speak for Canadian culture is to recycle the identity-as-landscape narrative with all of its binaries. They do not call upon Canadians to do the work of reimagining ourselves wherever we are.

Perhaps the following questions could have been asked instead: Why are these two questions being asked? Who is doing the asking?

Such questions are productive in that they ask us to think about the motives behind the construction of categories such as “Canadian art” and “Canadian culture.” Such questions are also productive in that they shift the question of who speaks for Canadian art and culture to the question of who is and who is not being listened to.