Inclusion, diversity, visibility, representation. They’ve all started to feel like empty buzzwords, slowly stripped of meaning with each comatose talk, panel or forum purporting to establish real change. Usually well-intentioned but lacking in concrete action, such circular discussions feel futile. Whether about the disparity between white art professionals and everyone else or the gendered career plateaus women face, we’re often left wanting. A number of factors are at play here, namely the rise of fake “wokeness,” where people (and institutions) want to align themselves with the right politics, but only superficially. It’s good PR to be pro-diversity, but it takes actual work—unglamorous, uncomfortable work.

This is frustrating because, despite the aforementioned, we need more inclusion, diversity, visibility and representation. But it should be genuine. We discuss these topics ad nauseam because they are, still, absolutely crucial. The problem is in moving conversations from the hypothetical or theoretical realms to ideas that are practical and actionable.

When it’s done right, something exceptional happens.

The inaugural Black Curators Forum, which took place in Toronto over the last weekend of October, was a gathering of around 20 Black curators, writers, academics and art workers from across North America. The forum was the brainchild of Dominique Fontaine, curator and founding director of Aposteriori; Gaëtane Verna, director of The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery; Julie Crooks, associate curator of photography at the Art Gallery of Ontario; and Pamela Edmonds, senior curator at the McMaster Museum of Art. A grant helped cover travel costs so curators from different areas of the country were represented.

The Black Curators Forum dinner, in Rashid Johnson's Anxious Audience at The Power Plant, 2019. Photo: Henry Chan.

The Black Curators Forum dinner, in Rashid Johnson's Anxious Audience at The Power Plant, 2019. Photo: Henry Chan.

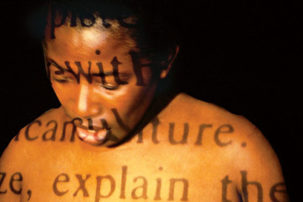

I was invited to document the event and got a look into the (purposefully) invitation-only forum. On the first night, we broke bread in the centre of The Power Plant, flanked by American artist Rashid Johnson’s series Anxious Audience. Conversation shifted from sober retellings of art-world micro- and macroaggressions to jovial laughter. Although it was a sociable communion of old friends and new faces, Verna’s opening remarks lingered throughout the dinner: “Each time I acknowledge the land that our gallery stands on, I think about erasure—of people and of stories. I think about those who have the privilege of writing history and about the people they choose, sometimes violently, to ignore. I think about the many trailblazers who paved the way for us to be here tonight, but whose stories are largely untold.”

Her words foreshadowed a weekend of talking and planning, re-mapping history and building intergenerational networks and systems of survival. The forum was inspired by an imperative to write the contributions of Black curators back into the narrative of the Canadian art landscape. Some of the trailblazers Verna referred to included Andrea Fatona, Josephine Denis, Betty Julian, James Oscar, Geneviève Wallen, Mark Campbell, Alexa Joy, David Woods, Cheryl Blackman, Eunice Bélidor and Liz Ikiriko.

“I met a group of ridiculously badass people who should be more known,” says Alexa Joy, an artist, activist and researcher from Winnipeg. “I’m disappointed in the lack of recognition, at least within my personal circles, of the work that’s going on across the country.” When reflecting on the forum, she recalled an immediate and electric solidarity among the participants.

Since the dissolution of Canadian Black Artists in Action (CAN:BAIA) in the 1990s, there’s been no national organization or group to connect Black artists and curators. There are many impeding forces that make it so a Black curator is never just a curator.

Since the dissolution of Canadian Black Artists in Action (CAN:BAIA) in the 1990s, there’s been no national organization or group to connect Black artists and curators. There are many impeding forces that make it so a Black curator is never just a curator. From being the only Black person working within art institutions (and having to democratize those institutions), to straight-up anti-Black racism, the burden of emotional labour, being pigeonholed, being expected to represent an entire community, getting called on for one month of the year (you know which one), needing a higher level of post-graduate education to even be considered, having to tiptoe around white supremacist authority, having to bite their tongues—it’s a lot.

But the forum didn’t dwell on these issues—it held space for grievances and validated each others’, but it was really about finding solutions.

“We took time to talk about what our experiences were but I think the fact that we focused on the type of action we should be taking, and what questions we should be focusing on moving forward was definitely what kept the forum as enriching as it was,” says Josephine Denis, a curator and advocate based in Montreal. “We were all very aware that we had limited time, that this was quite rare as an occasion. And so we made sure the conversation revolved around the next steps.”

On Saturday, October 26, over the course of seven hours spent in the lower concourse of the AGO, those steps started to take shape. American curator Courtney J. Martin, director of the Yale Center for British Art, gave an insightful talk to open the day, dispelling typical excuses for why Black art isn’t part of institutional collections, discussing survival within institutions, countering the pervasive idea that there are more opportunities for Black curators in the United States and pointing out the need for fellowship the higher up the ladder you go.

During the roundtable discussion, a few points resurfaced over and over around the creation of a national vision or directive for Black art in Canada, and the need for more scholarship about historical and contemporary Black Canadian art to connect to a wider art history. The conversation also touched on ideas about how to be part of the institution but not institutionalized and developing a countrywide network of curators to influence social, political and institutional practices related to Black art.

From left to right: Dominique Fontaine, Julie Crooks and Pamela Edmonds at the Black Curators Forum, 2019.

From left to right: Dominique Fontaine, Julie Crooks and Pamela Edmonds at the Black Curators Forum, 2019.

One thing I’ve been ruminating on is the sense of responsibility Black curators must bear—to the work that was done before them, to the Black and non-Black artists they work with and to leaving the industry better than they found it for the next generation—in a way that is not expected or required of their white colleagues. One must simultaneously be concerned with personal career growth and their role as a catalyst in an industry where their presence and work can change things. Black curators and arts workers often take on this additional work without a second thought; it seems embedded in the very essence of their practices.

As a Black writer, I feel a responsibility to tell stories with care, to oppose misrepresentation and to write Black artists’ work into the Canadian art canon. I approach writing and criticism about Black art with trepidation for the same reason. I wonder if I risk further marginalizing an up-and-coming Black artist or curator if I give their show a negative review, for example. But then no writing at all means a lack of textual traces, offering little evidence that the work existed in the first place. Perhaps I’m being too precious. Not all criticism of Black art needs to be celebratory or fawning—that hinders constructive discourse—but it definitely needs to be rooted in an ethos of care.

Wary of participating in the erasure I’m attempting to combat, I’ve started considering how the work of different Black curators and thinkers informs and builds upon itself. Earlier this year, the collective Black Wimmin Artists hosted “The Feast” at the AGO, inviting 100 Black women and non-binary art professionals, artists and academics to come together to take up space and commemorate the contributions of the collective Diasporic African Women’s Art (DAWA), specifically their 1989 touring show “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter.” In 2014, Andrea Fatona spearheaded the conference “The State of Blackness” at OCAD University, which led to the creation of a database in 2017 of artworks, essays, oral history interviews and research papers produced by and about Black Canadian artists, critics and curators from the late 1980s onward. And in late November of this year, a public symposium, “Bodies Borders Fields” at the Toronto Media Arts Centre, which was convened by Denise Ryner, director/curator at Or Gallery, in collaboration with Yaniya Lee, features editor at Canadian Art and one of the Black Curators Forum participants, re-imagined a 1967 cross-border conversation between Toronto and New York artists about “blackness” in art. Edited by art historian Charmaine Nelson, Towards an African Canadian Art History: Art, Memory, and Resistance, the first book of Black Canadian art history, was published in 2018. Much of this history is oral, so having texts that can document it is integral to understanding a broader narrative. At the Black Curators Forum, many participants vowed to start more scholarship in this vein, especially working collaboratively, and to preserve the documentation properly once it’s produced. During discussions, Pamela Edmonds likened being a Black curator to working as an archivist.

Black Curators Forum participants at the AGO, 2019. Photo: Sandy Pranjic.

Black Curators Forum participants at the AGO, 2019. Photo: Sandy Pranjic.

Artist, writer and curator David Woods’s decades-long career embodies Edmonds’s point. In an interview he told me that “people don’t know the art history because much of it has been unwritten.” Originally from Dartmouth, Woods co-curated “In this Place: Black Art in Nova Scotia,” the first-ever show of African Nova Scotian art, in 1998. When researching and collecting works for the show, Woods would go to people’s homes and find whatever treasures were hidden in the recesses of their basements. He found works by Edward Mitchell Bannister, George McCarthy, Edith MacDonald-Brown and Harold Cromwell—not necessarily household names, but Woods makes a case for why they should be.

“Every time I go to the National Gallery [of Canada], I feel a sense of being very deeply wronged because of the complete lack of representation of African Canadian art there,” Woods tells me. “The last time I went [in February, 2019] they had three or four pieces of Black folks that were created by white artists. And that seemed to be their projection of Black art, or at least their way of paying some homage to Black art. But it wasn’t created by us.”

Having the historical context helps contemporary Black artists ground their work, as in the case of Halifax-based Letitia Fraser, whose paintings are influenced by the tradition of African Nova Scotian quilt-making, and she was influenced by Woods’s work on Black Canadian folk art.

During the forum, one participant cautioned that we needed to be careful not to erase each other. It made me consider who may have been missing from this conversation, and whose concerns weren’t being raised.

Outside the urban centres of Montreal, Vancouver and Toronto, the lack of artistic diversity and representation is exacerbated by smaller population sizes. For Alexa Joy, it’s been an uphill struggle, through bureaucracy and ignorance, to do her work in Winnipeg. She founded Black Space Winnipeg, a grassroots organization that hosts events, demonstrations and workshops to increase the artistic development and visibility of Black communities. And in 2016, fed up with the Eurocentrism of Winnipeg’s Nuit Blanche, she started Nuit Noire with the help of different community leaders like artist Gibril Bangura. “There’s not a huge emphasis on Black art within the public art of Manitoba,” she said during a post-forum interview. She’s glad to be able to provide this space because there are “so many talented individuals and they don’t have the professional platforms to showcase their work. They need opportunities.”

During the forum, one participant cautioned that we needed to be careful not to erase each other. It made me consider who may have been missing from this conversation, and whose concerns weren’t being raised. After all, the forum was invitation-only and not open to the public (mainly to ensure it was a space for open and uninhibited dialogue) and it was predominantly for curators, unlike a lot of similar events that centre artists.

This was also the inaugural event, and it seems the next one will involve even more voices. For many of the participants it was a chance to meet for the first time and create connections. After hours of hammering out ideas to influence policy, hold cultural institutions accountable and reaffirm Black Canadian art contributions, we needed a reprieve. A dinner of oxtail, jerk chicken and rice and peas was served at Crooks’s home, allowing participants to splinter off and have more intimate conversations. Eventually, someone found the piano and a sing-a-long began. Gathering without any pressing goals created a restorative power and acted as a balance to the weighty discussions of the day.

The weekend closed with a private viewing of the late Denyse Thomasos’s abstract paintings at Olga Kolper Gallery over breakfast and a tour focusing on Black artists at Art Toronto—although that turned into more of a scavenger hunt than a tour. After a lecture by Denise Ferreira da Silva, we bid each other farewell.

But the goodbyes felt temporary. Over the course of three days together, there was a sense we’d had a deep and tangible impact on each other. Participants left the weekend reinvigorated, with projects percolating. Intergenerational dialogues were especially fruitful, addressing mentorship and legacy. Josephine Denis reflected on the responsibility she feels to honouring the past, to remember the lessons she’s learned from her mentors. It’s important, she says, “to make sure that we’re not having the exact same conversations or if the exact same conversations are imposed on us, that we know that past generations did the work already.” Her personal and professional focus is to care for and support living artists, to assure they’re represented equitably in institutional spaces and to make their work visible and accessible to hinder future erasure. As head of public programs and outreach at SBC Gallery of Contemporary Art in Montreal, Denis creates networks between artists, community leaders and the institution. In January 2020, she is organizing an event to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the earthquake in Haiti that displaced hundreds of thousands of people, which will reflect Montreal’s dynamic Haitian community.

If anything, the forum was a testament to the ongoing tenacity of Black curators in Canada. Despite the external forces they grapple with, they always make time for caretaking, for mentorship, for dialogue that can lead to evolution. It may be unglamorous, uncomfortable work to critique the ways the system is set up to favour and centre whiteness, but they’re doing it, every day.