The Cree language—I’ve heard it described as lyrical and lilting. I’ve heard it moving in and out of the mouth in breaths. I’ve heard it spoken quickly and, in my home, slowly. I love the sound of old men’s voices speaking their tongue in prayer. I love the voices of old ladies speaking their tongue in laughter. I love the voices of young people speaking their language in camaraderie.

I love the sound of my tongue navigating two languages, the tongue of my father and the tongue of my mother; I carry his language of English as a weapon and I carry her sound like an invitation to let me in. It is difficult when living between two heritages; not confused, but sometimes a being is held a little tighter by one language than the other due to the politics of skin and voice, depending.

Language and its implications are what first drew me to Cree Métis artist Jason Baerg and his project ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World). In this project, language and its manifestations work to ground notions of the Anthropocene, survivance and Indigenous connection to land and environment.

Recently, I worked with Baerg to present ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World) at Wanuskewin Galleries, in the artist’s home territory of Saskatchewan—and my immersion in the work deepened.

Installation view of Jason Baerg’s (from left) ᐋᐧᐸᓇᑖ Wâpanatâhk, which means Morning star in Cree, ᐋᐧᓴᑳᒼ Wâsakâm, which means Along the shore in Cree, and ᒋᐢᑖᐁᐧᐤ Cistâwew which means Echo in Cree, all 2016. Installation view at Wanuskewin Galleries in 2017. All works are acrylic, tempera and oil on laser cut canvas. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

Installation view of Jason Baerg’s (from left) ᐋᐧᐸᓇᑖ Wâpanatâhk, which means Morning star in Cree, ᐋᐧᓴᑳᒼ Wâsakâm, which means Along the shore in Cree, and ᒋᐢᑖᐁᐧᐤ Cistâwew which means Echo in Cree, all 2016. Installation view at Wanuskewin Galleries in 2017. All works are acrylic, tempera and oil on laser cut canvas. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

As soon as I read the titles of Baerg’s works, which are all in Cree, my mind became activated with their possible meanings and purposes. “What are these words to Jason?,” I wondered.

And when I encountered Baerg’s groundings of these Cree words in the studio within a series of abstract paintings, a video and an installation—and later, when I helped install these works and words in a city where I live, at a park where Indigenous peoples of the Northern Plains have gathered year after year—well, then these symbols became even more compelling to me.

That is, if language is what first drew me to Baerg’s work, the materials and methods used to manifest them compelled me even further. Baerg follows in the steps of other Indigenous artists who have utilized the powerful strategy of abstraction—artists such as Alex Janvier, Leon Polk and Rita Letendre—to achieve his own contribution to the genre. When this abstract work is situated in his home territory of Saskatchewan, I think of the northern petroglyphs on the cliff faces of the Churchill River, or perhaps the ribstones found in the south, at Herschel. In these older glyphs and objects, I find motifs reminiscent of those in Baerg’s art—an art powerfully connected to the land.

Installation view from Jason Baerg’s ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World), exhibited in 2017 at Wanuskewin Galleries in Saskatoon. ᐅᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ Oyasiwewina, which means The law in Cree, is at left. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

Installation view from Jason Baerg’s ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World), exhibited in 2017 at Wanuskewin Galleries in Saskatoon. ᐅᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ Oyasiwewina, which means The law in Cree, is at left. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World), as a project title, is a humorous play on the philosophy of manifest destiny and settler encroachment into North America. Paulo Friere coined the phrase “name the word, name the world.” This naming has a tremendous ability to change our colonial realities.

Let’s be clear on this: No, it is not enough to say to Indigenous people, “Let me add some signs in your language inside my institution so that you feel included.” Rather, to actively name and to re-name—both within and beyond art—is to re-appropriate sites of colonial violence inside and outside of the white cube. The act of re-naming in our Indigenous language is as inclusionary as it is transforming; it activates space and works to de-centre Western-centred knowledge.

Accordingly, for ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World), Baerg gave very particular and meaningful names to a series of five works in acrylic, tempera and oil on laser-cut canvas:

ᐋᐧᓴᑳᒼ Wâsakâm, which means Along the shore in Cree

ᒋᐢᑖᐁᐧᐤ Cistâwew, which means Echo in Cree

ᐋᐧᐸᓇᑖ Wâpanatâhk, which means Morning star in Cree

ᐸᑯᐦᒉᓀᐤ Pakohcenew, which means S/he Removes its intestines in Cree

ᓂᑕᐧᑯᓀᐦᐅᐁᐧᐤ Nitwakonehowew, which means S/he makes an opening in the snow for people in Cree

Working together on installing these works at Wanuskewin in recent months, Baerg and I talked about making these names part of the installation itself. Prior to installation, Baerg had explained that the canvases sit atop each other, propped up by the floor and the wall. Installing the paintings in this way, the artist hoped, would work to ground the artworks to the land and the language it holds, evoking that connection literally. The floor of the Wanuskewin Gallery, by coincidence, is an earthy brown tone; we installed the syllabic titles next to each work on that floor, letters in yellow ochre, so that the titling or naming itself became another attempt to connect to the earth.

Detail of Jason Baerg’s ᐋᐧᓴᑳᒼ Wâsakâm, which means Along the shore in Cree, exhibited in 2017 at Wanuskewin Galleries in Saskatoon. Names of each of the works were affixed to the floor. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

Detail of Jason Baerg’s ᐋᐧᓴᑳᒼ Wâsakâm, which means Along the shore in Cree, exhibited in 2017 at Wanuskewin Galleries in Saskatoon. Names of each of the works were affixed to the floor. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

Also in the ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World) exhibition were two other elements created from oil and tempera on laser-cut canvas, works that had these names:

ᐅᓅᒋᐦᐃᑐᐃᐧᐲᓯᒼ Onôcihitowipîsim, which means September-the mating moon or month in Cree

ᐅᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ Oyasiwewina, which means The law in Cree

These two works dealt more directly with matter and energy, their cut canvases creating movement and play with light. In dealing with matter, in being changeable, they evoked, for me, the transformative power of a visual response to visual culture. Light was directed from mating moon into the gallery space, while shadows cast by The law played onto a gallery wall; both works were grounded through language and earth as touchstones.

I was reminded, in considering the light and darkness cast by these artworks, how creation has a natural order or law that we as Indigenous people watch, follow and adhere to for our survival. In this respect, these two works also served as a visual response to another very particular term—the Anthropocene—and the consequent ecological impact that is occurring at momentous speed, often impacting Indigenous peoples more severely than others.

A view of Jason Baerg’s cut-canvas work ᐅᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ Oyasiwewina, which means The law in Cree, at Saskatoon’s Wanuskewin Galleries in 2017. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

A view of Jason Baerg’s cut-canvas work ᐅᔭᓯᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ Oyasiwewina, which means The law in Cree, at Saskatoon’s Wanuskewin Galleries in 2017. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

As Kyle Whyte has put it, we are at a moment of “colonially induced environmental changes [that have] altered the ecological conditions that [have] supported Indigenous peoples’ cultures, health, economies and political self-determination.” Whyte also points out that “anthropogenic climate change affects Indigenous peoples earlier and more severely than other populations. Indigenous people, for example are among the first ‘climate refugees’ in regions such as the Arctic or Pacific where sea-level rise is occurring.”

The notion of the “climate refugee” is interesting to me; I can relate and contemplate my own experience as a “climate refugee” too. In so-called Canada, we live in a climate of corporate imperialism, whether it is uranium mines poisoning our water or hydroelectric dams displacing communities or either of these industries affecting water tables to the extent that fishing and hunting are impacted, causing huge deficits monetarily, as well as within Indigenous traditional diets.

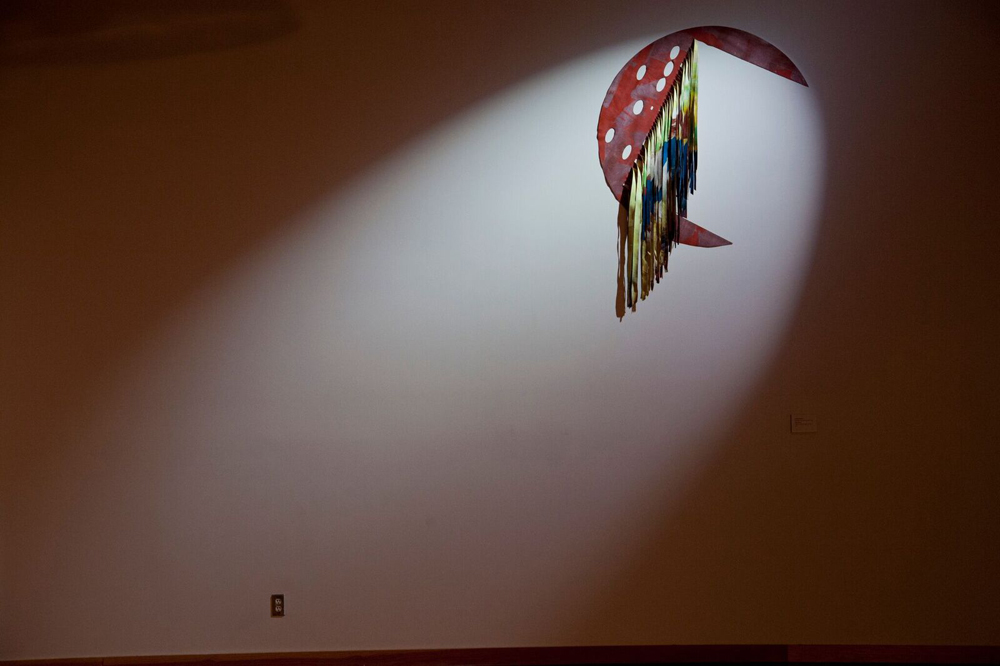

An installation view of Jason Baerg’s ᐅᓅᒋᐦᐃᑐᐃᐧᐲᓯᒼ Onôcihitowipîsim—which means September-the mating moon or month in Cree—at Saskatoon‘s Wanuskewin Galleries in 2017. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

An installation view of Jason Baerg’s ᐅᓅᒋᐦᐃᑐᐃᐧᐲᓯᒼ Onôcihitowipîsim—which means September-the mating moon or month in Cree—at Saskatoon‘s Wanuskewin Galleries in 2017. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

Onôcihitowipîsim and Oyasiwewina, being responsive or held in balance with other elements of light and setting in ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World), are works remind me that when we do not live in balance with spiritual or natural law, our environment shifts negatively and we become displaced. Hunters must follow the seasons to hunt certain animals and leave others to replenish; people must respond to the seasons to move camp in order to better survive harsh environmental conditions.

While installing and later interpreting and considering ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World), notions of climate refugee nestled within a feeling of refuge, of immersion in a place of safety. In this project, Baerg processes land, animals and sky through technology—the technology being the mediums of paint and cut canvas—which in turn create a refuge of land and environment, or flesh. He creates this environment by viewing and visually interpreting the land, animals and sky through the Cree language—it is his lens. In Wâsakâm, Cistâwew, Wâpanatâhk, Pakohcenew and Nitwakonehowew, we view these words translated into powerful art works. Overall, for me, it argues that the power of life lies in the utterances of the tongue, and it reminds that earth is a tangible touchstone for spiritual reconnection.

We see this power of material-linguistic translation pushed even further in Baerg’s video installation Pihtôpitew, which means S/He Peels it off by pulling. Among other elements, this work incorporates visual responses to audio of Stephen Harper’s official 2008 apology to residential school survivors.

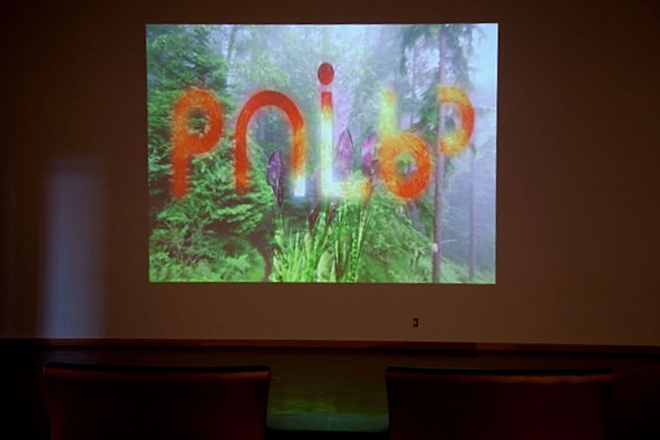

An installation view of Jason Baerg’s video Pihtôpitew, which means S/He Peels it off by pulling in Cree, at Saskatoon’s Wanuskewin Galleries in 2017. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

An installation view of Jason Baerg’s video Pihtôpitew, which means S/He Peels it off by pulling in Cree, at Saskatoon’s Wanuskewin Galleries in 2017. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

“Pihtôpitew navigates through time, considering that which has carried us beyond multiple traumas including acculturation, dispossession and the residential school system,” Baerg says. “Pihtôpitew aims to swell above any submission to the devastation colonization continues to have on this land and her people. Like the crocus, the first flower of spring that breaks through the ice, Pihtôpitew illuminates continuum, Indigenous relationality and survivance.”

The visible enunciations and pulsating utterances of Cree language in Pihtôpitew are “talking back” to a man—and not just any man, but one who epitomizes colonial power.

These utterances reverberate continuously in Pihtôpitew. At first, they read tapwewin, tapwewin, tapwewin in syllabics, which means truth; this is a statement, a demand from the people for truth. The second word to “talk back” is kitimâkan, kitimâkan, kitimâkan in syllabics ᑭᑎᒫᑲᐣ—this says to Harper, “Pitiful!” Then the third word is dragonfly in Cree syllabics, ᒍᐦᑲᓇᐱᓭᐢ: this speaks to the transformative power of our language.

From first becoming aware of Baerg’s art, to seeing it in the studio, to helping him install it at Wanuskewin, to considering it afterwards, many words have echoed through my mind. I hear the sounds of women, of men and of our young people within this work and within this wider project. Through this language, through this art, I hear the activation a site of transformation, a re-naming of a new world.

Felicia Gay is Swampy Cree/Scot from Cumberland House. She has worked as a curator of Indigenous contemporary art for the past 14 years, and currently she is curator at Wanuskewin Galleries in Saskatoon.

Two works in acrylic, tempera and cut canvas from Jason Baerg’s ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World), exhibited in 2017 at Wanuskewin Galleries in Saskatoon. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.

Two works in acrylic, tempera and cut canvas from Jason Baerg’s ᐅᐢᑳᔨ ᐊᐢᑮᕀ Oskâyi Askîy (New World), exhibited in 2017 at Wanuskewin Galleries in Saskatoon. Photo: Patricio Del Rio.