In the 1970s Igloolik was the last town in its region to get a cable television connection. The town voted, twice, against having cable TV brought into their homes. It might seem that access to cable TV is an easy choice, and one could even ask, Why bother fighting it, the “idiot box”? But the residents of Igloolik, and all over Inuit Nunangat, were experiencing huge shifts in their ways of living. They were constantly learning to live differently, and these cumulative changes made their day-to-day human experience much different than ever before. With very not-Inuk stories on cable TV, why should Inuit have been expected to accept it with open hands? How well would children who grew up with television be able to connect to Inuit culture? Some 20th- and 21st-century technologies were seen as a barrier, a threat that might sever Inuit from existing with and connecting to knowledges of ancestors come and gone. But now we see that threat, that impending blade, as a mirror that we can use to reflect our light even farther than before. The camera is a tool we use, and interpret, as another way of being ourselves and connecting with our families through time, as we come and go in our existence as humans. With the creation of the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation in 1981, cable TV was brought to Igloolik but it was accepted only on the condition that Inuit would be equal: Inuit had to be present onscreen. This decision was a powerful demonstration of human intelligence, grace and drive. It’s an example of vision, of identifying a problem and working it out. If you want your children to know where they come from, you have to show them where they come from—with all the tools possible.

If you want your children to know where they come from, you have to show them where they come from—with all the tools possible.

The Inuit Broadcasting Corporation had its limitations, so the need to find a way to explore political ideas pushed Zacharias Kunuk, Paul Apak Angilirq, Pauloosie Qulitalik and Norman Cohn—who had collaborated on film projects since 1985—to create Igloolik Isuma Productions Inc. in 1990, now often referred to simply as Isuma. Their major contribution is a bountiful catalogue of film and video work spanning more than 30 years. Their output is just a glimpse of the wonderful ways the Isuma team has tended their little corner of the world: the way they have empowered and fought to work in a paradigm that matches the values of the collective—community, voice and accessibility are some of the integral values that guide their work; the way those values are present, both in the films onscreen and in the many ways of working and living off-screen; and the way they maintain the social support structures that have kept Inuit strong over thousands of years living out on the Nuna. Isuma has created a network of capable people who communicate and listen to each other through various working tasks that change constantly. All are honed into a shared set of values that guide the work to be done. Working with others is a pleasure when you’ve taken the time to arrive on the same page.

Isuma’s methods are, like many artists, also guided by technological advancements, which can bring with them a change in the abilities of creators, and often a change in aesthetics too. When sound was brought to screen and the talkie emerged, storytelling in motion pictures changed drastically. French New Wave blossomed in the 1960s with the availability of the Eclair Caméflex. The lightweight camera changed the possibilities of filming and there could be a bit more playfulness in the way scenes were captured, which produced a noticeable shift in the aesthetics of film at the time. When the hand-held camera was invented, it made filmmaking more accessible to creators who couldn’t get behind the camera before. The hand-held camera changed the way directors like Agnes Varda worked, with the intimate The Gleaners and I (2000) as an example. The HD camera and improved digital storage made the single-shot feature Russian Ark (2002) possible. Although it is possible to film in the cold of the Arctic winter, as the skilled Inuit film technicians who worked off-camera on Nanook of the North proved, it’s definitely not preferable. When it comes to Isuma, these smaller, more agile cameras are the key to unlocking a universe. The hand-held video camera can really be thanked for the great service of bringing Inuit cinema to us—I mean, think about the freedom needed to film a man running naked across the sea ice!

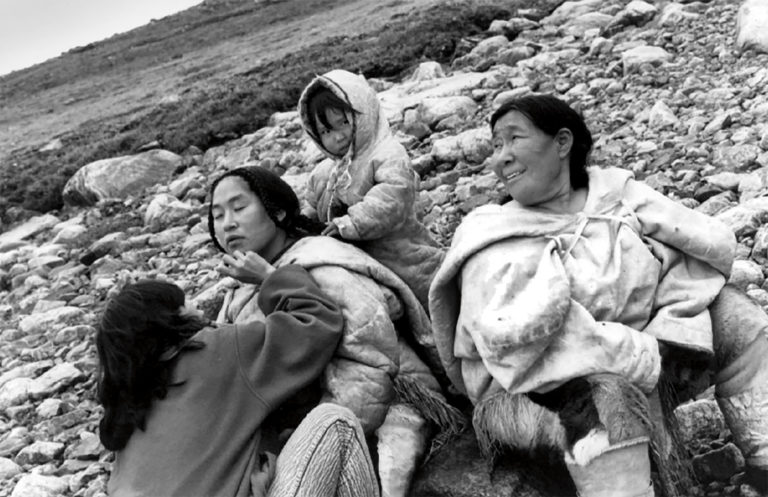

Theresa Ipkanak, Sylvia Ivalu and Bernice Ivalu on the set of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk. 2001. Film, 174 min. Courtesy Isuma Distribution International.

Theresa Ipkanak, Sylvia Ivalu and Bernice Ivalu on the set of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk. 2001. Film, 174 min. Courtesy Isuma Distribution International.

On the set of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk. 2001. Film, 174 min. Courtesy Isuma Distribution International.

On the set of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk. 2001. Film, 174 min. Courtesy Isuma Distribution International.

When I attended film academy one of the first things we learned was the hierarchy that exists on a film set. This hierarchy depends on nearly the entire team succumbing to a prescribed order. All control and decision-making power is left to the director or producer. I find it hard to believe, when working with so many people who are talented and skilled in so many different ways, that their voices should ever be stifled. Having leaders is important, but in my experience and understanding of the world it’s always valuable to have people chime in with their own understanding of a situation. The lessons I had to learn about running a film set assumed that I would buy into a structure of life and living that values one person over others. When I take the time to step back, to understand how someone like me prefers to work, it looks way different from what I was taught.

Directed from an Inuk point of view, Isuma’s films and videos bring important perspectives to the screen. There isn’t one simple truth in the world, so understanding a subject requires listening to many perspectives.

Isuma’s workflow and structure follows a route that is more culturally relevant to Inuit ways of working. Many people are valued, and many opportunities are created. Starting at the beginning of each film’s production cycle, many people help form the core ideas of the film’s subject matter. Multiple minds give input on the right way for a story to be told, especially if it is something based in historical events and customs. A huge part of creating these films is the foundation of knowledge that Elders in Igloolik hold. Isuma follows the values of the collective culture while making films, and the results of all those conversations become what appears onscreen. There is still organization, with normal film roles like writer, grip and actor. And there is always a director, or trusted leader, and this person listens, guides and, when needed, makes decisions for all. Having someone to trust with keeping the bigger picture in mind, and steering everyone in the right direction, is key. But it also takes set designers, costume makers, accountants and so many other people to make a film set work. They all deserve respect.

The discussion around Inuit representation in film has expanded so much in recent years. In Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001) and so many other works since, it has been proven that there are many tremendously talented local actors to play these roles. Some actors have expanded their careers to participate in films made by people outside Inuit culture but who want to include Inuit characters in their work. It’s important to see people who look like you onscreen because it helps you understand how you fit in the world. It shows you that your experience is valid, and that other people have gone through what you have. Always directed from an Inuk point of view, Isuma’s films and videos bring important perspectives to the screen. Their projects share stories of Inuit who have been disempowered, and who find power by being given the opportunity to speak up. There isn’t one simple truth in the world, so understanding a subject requires listening to many perspectives. Isuma isn’t the one and only voice for Inuit, but they do cover a vast array of topics, including relocations, climate change and international social politics.

Abraham Ulayuruluk on the set of The Journals of Knud Rasmussen. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk and Norman Cohn. 2006. Film, 112 min. Courtesy Isuma Distribution International.

Abraham Ulayuruluk on the set of The Journals of Knud Rasmussen. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk and Norman Cohn. 2006. Film, 112 min. Courtesy Isuma Distribution International.

Alootook Ipellie, The Idiot Box Is Here, 1975. Pen and ink on paper, 26.8 x 20.9 cm. Reproduced with permission of the estate of the artist. Courtesy Richard F. Brush Art Gallery, St. Lawrence University, Canton, NY.

Alootook Ipellie, The Idiot Box Is Here, 1975. Pen and ink on paper, 26.8 x 20.9 cm. Reproduced with permission of the estate of the artist. Courtesy Richard F. Brush Art Gallery, St. Lawrence University, Canton, NY.

In many ways the film- and video-making worlds work to bring things forward in time with us. Making historically accurate films requires knowing all the details of a story, including knowledge of interpersonal dynamics, the possible circumstances people could find themselves in as well as details of costuming and set design. It requires keeping alive the knowledge of patterns for objects from pants to necklaces, and even details like how the dwellings are placed and how large they are. As many elements as possible are thought of and presented in ways that would have made sense, as far as we can understand, to Inuit families living 200 years ago. Going deeper and deeper into those details makes robust works of art. In the process of producing historically accurate narrative films, the knowledge of Elders is being shared, heard and valued. This gives us a rich creative video archive for youth to grow up with. Isuma’s body of work is something concrete for the generations that follow to learn from, including myself. It has the potential to reach youth who have varying levels of connectedness to Inuit cultural lessons and ways of being. For youth with different degrees of knowledge of our collective history, Isuma’s body of work gives living Inuit a portal into what and who Inuit were, and are.

For youth with different degrees of knowledge, Isuma’s body of work gives living Inuit a portal into what and who Inuit were, and are.

In Isuma’s work I see that the histories of different nations affect each other, how intertwined we are. In one episode of the Nunavut (Our Land) (1995) series, which is set in the 1940s, there is a scene in which a group of Inuit are sitting around in their qammaq, and one of them talks about a dream he has of flying to Europe to kill Hitler. It really struck me, because too much of the language around Inuit is about the “isolation,” the “remoteness,” the idea of being disconnected. It’s easy to imagine, when using the language of distance, that Inuit live outside the historical Western context of the rest of the world. In this one scene, that idea is completely collapsed. Suddenly you understand that while this family is living out on the Nuna, hunting, sewing and doing all the beautiful things that happen in life, there are people on the other side of the world, also living and falling in and out of love—and in that example, at that moment, dying at the hands of genocide. It presents a scene of potent empathy. In Arviq! (2002), the opening is a short lesson on whaling in the 1800s, revealing how much the bounty of the waters Inuit hunted in changed the lives of Europeans —perfumes, combs and lamp oil were made from parts of the whale. When overhunting caused a need to get materials elsewhere for the combs and oil, it was easy for Europeans to move along and find another resource to exploit, and they turned toward fossil fuels and plastics. For Inuit, however, it is not just a want for resources; the relationship to the bowhead whale is personal. That relationship continues today, even though the number of whales has become so few. Arviq! is the story of Inuit living during the mid-1990s and dealing with the aftermath of the 19th-century whaling industry, even though the rest of the world has forgotten and moved on. Even on our Nuna, the remains of old rusty whaling stations still stand.

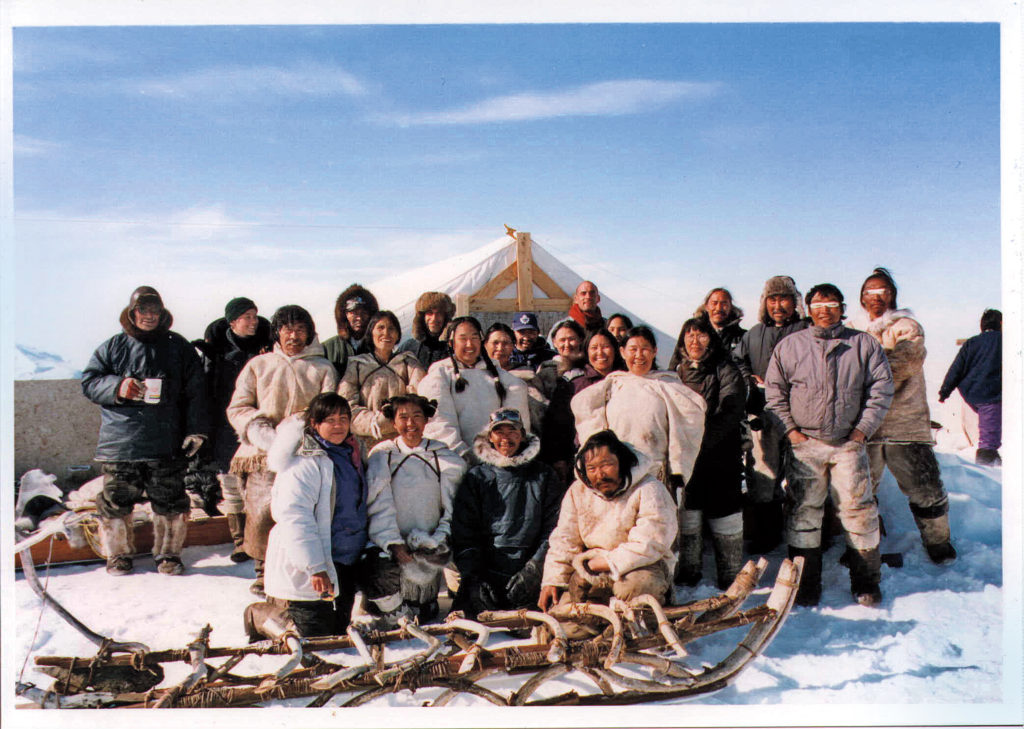

Cast and crew on the set of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk. 2001. Film, 174 min. Courtesy Isuma Distribution International.

Cast and crew on the set of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk. 2001. Film, 174 min. Courtesy Isuma Distribution International.

Events happening elsewhere affect us too, even in Inuit Nunangat. The subject matter of Exile (2009) speaks to this interconnectedness, specifically in terms of the Cold War politics of the 1953 High Arctic Relocation, which had a long-lasting impact and deeply affected Inuit. This film is special because it serves as a platform for relocatees to recount their experiences—and it should be understood that so many Inuit have experienced relocation in one way or another. It allows for those who experienced the event to speak, and for others to step back and take the time to listen, which is also what viewers must do. Inuit Piqutingit (2009) reminds me of our connection to Indigenous people around the world. The film broaches the subject of the repatriation of objects, asking, What belongs to Inuit? Objects being held in international museums and galleries have the tension of questions of ownership surrounding them. This question of belongings affects so many Indigenous people all over the world. While Isuma stays true to its roots in Igloolik, voices from other regions also get the opportunity to dialogue throughout the catalogue of films. Inuit Cree Reconciliation (2013) heads over to Nunavik and reveals the tensions between Inuit and Cree living in Kuujjuarapik/Whapmagoostui. That gesture of listening reminds me of a 2017 tweet from Su’ad Abdul Khabeer: “You don’t need to be a voice for the voiceless. Just pass the mic.” A good portion of Isuma’s documentary work could be placed in this category of “mic passing.” Finding those Inuit who have experienced severe injustice and handing over the mic is like saying, I see you, I want to hear how you feel. I can’t help but feel deeply touched by the notion of Inuit first creating and then passing a microphone, or video camera, to each other.

For Inuit who have experienced severe injustice, handing over the mic is like saying, I see you, I want to hear how you feel. I feel deeply touched by Inuit first creating and then passing a microphone, or video camera, to each other.

Connecting directly to Inuit who have experienced the events these films speak about is so vital: the closer you get to a story, the closer you get to understanding it. This work is guided by values, and letting people speak for themselves is one of them. Often we live by other people’s rules. Many of us expect less than we deserve, not just as individuals but as a collective, as a culture. Because we expect less, we accept less. We are devaluing ourselves when we do this. Working with Isuma, seeing all the people required to make the work happen, makes me realize, so much, what a viewer doesn’t get to see in the results. There are things—intangible things, things we can’t film and things we can’t name individually. I can tell you that what I understand is this: Isuma has not only made strong work that takes a stand for people who too often have their voices stifled, or for people who don’t often get the opportunity to share their experiences. Isuma has not only created film work, but has fought day in and day out in order to work as a collective of artists, in order to maintain the right to the final cut, in order to have their voices heard on fair terms. Isuma has had to fight over the meaning of art, when organizations and funding bodies say that successful films cannot be considered art. I disagree. Great art has an emotional connection, whether it is commercially successful or not. That is how art can make real change. What I remember, whether it’s at the end of the day or five years later, is that it’s all about that emotion, and the emotional connection of an artwork. For me, what can change the way I live my life is the feeling.

The number one reason that I think Isuma is amazing is that their work carries those feelings with it; they are a group of people who genuinely care about others. The actions and beliefs of a single person do not make a culture. Together, as Inuit, we make our culture alive. Together, the continued care we put into things like language, clothing, song and story makes us alive, not just as people but as Inuit. It’s not just an identity. When it comes to the final product, Isuma’s mission is simple, and in opposition to the idea of the “idiot box.” Through all the steps it takes to make a film—pre-production, production, post-production and distribution—what sets the stage is compassion. The work that Isuma crafts stimulates learning and growth as people cultivate their minds, leaving room for everyone to be human.

Still from Maliglutit (Searchers). 2016. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk, co-directed by Natar Ungalaaq. Film, 94 min. Courtesy Kingullit Productions Inc.

Still from Maliglutit (Searchers). 2016. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk, co-directed by Natar Ungalaaq. Film, 94 min. Courtesy Kingullit Productions Inc.