How’s this for a drawing piece? A woman lines her eyes with kohl. She checks these thin black circles in a mirror to make sure they are perfect. Then she rubs the lines, blurring them. She rubs more, and kohl goes into her eyes, which redden and water. When the drawn line is dispersed, she begins lining her eyes with kohl again. And rubbing again. And lining again. This cycle repeats for 22 minutes, until the woman cannot open her eyes.

Or how about this? The same woman kneels on a 12-foot-by-12-foot canvas at the base of a large stairwell. The stairwell rises above, circling her body. She begins near centre of the canvas with a black marker. For two hours, she writes the same words over and over, spiraling from the centre until the words, in their repetition, are no longer legible, and the lines merge into a single form—a void, a portal, a galaxy.

Artist Tazeen Qayyum, based in Oakville, created both these works. The former, Blur, was made in 2015, while the latter, Unvoiced, was performed at the inaugural Karachi Biennale in the fall of 2017.

These works track a shift in Qayyum’s practice—a move away from the tight, clear precision of the Indian miniature painting she mastered years ago to something messier, something that binds legibility and illegibility, beauty and ugliness, process and product. Her past miniature painting work enjoyed sales at Christie’s in New York, a positive New York Times review, and a nomination for the Jameel Art Prize. But now this newer work is on view in “Tazeen Qayyum: Descent” at Canvas Gallery in Karachi.

“Descent,” on until March 1, includes Qayyum’s new black and white, circular text drawings based on the words Tauba (repentance), Ilzam (blame), Ashq-Ishq (Teardrop-Devotion-Passion) and Farz (Obligation / Presumption). It also includes video documentation of a 24-hour drawing performance—the documentation is in grid form, one panel for each hour, for a total of 24 circles expanding into being.

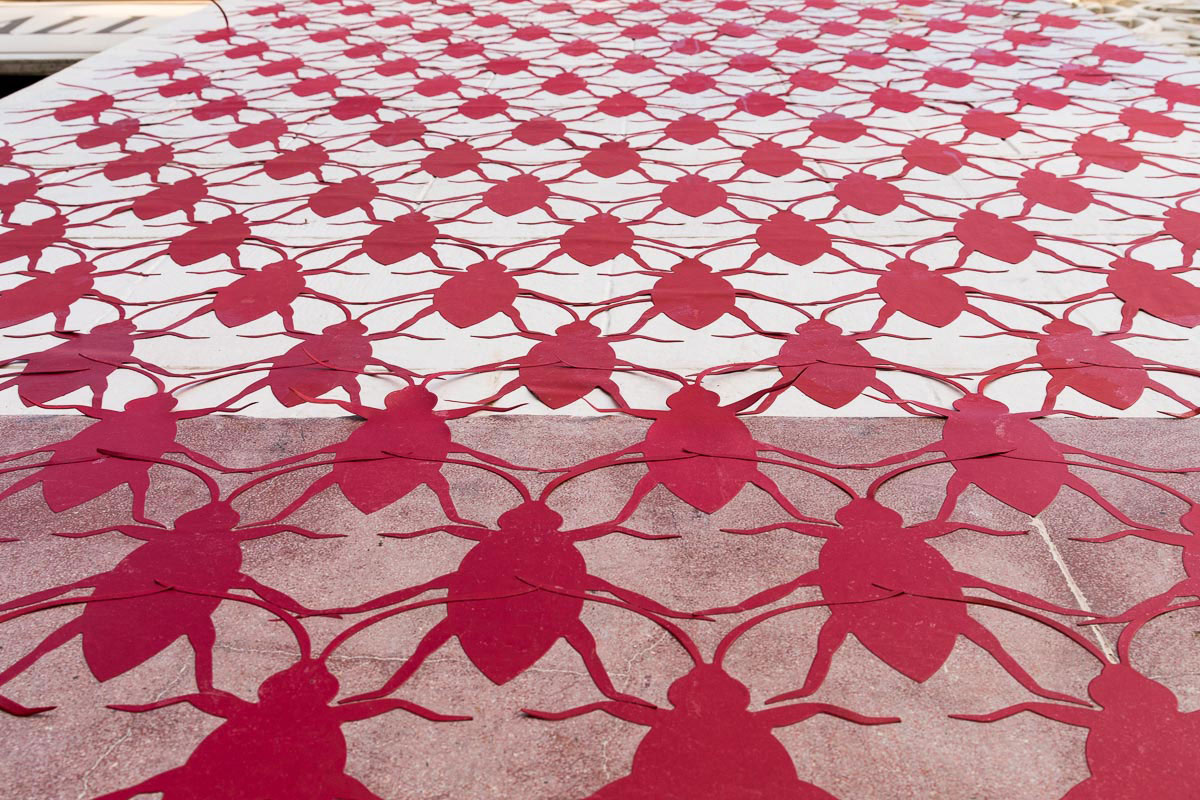

Interestingly, this practice all began with, and spiralled out of, a cockroach. Or, more precisely: hundreds and hundreds, or thousands and thousands, of cockroaches.

Tazeen Qayyum, Facade (detail), 2017. Site-responsive Installation at Jamshed Memorial Hall, Karachi Biennale 2017, site size: 45ft x 85ft. Courtesy Tazeen Qayyum. Photo: Mahmood Ali.

Tazeen Qayyum, Facade (detail), 2017. Site-responsive Installation at Jamshed Memorial Hall, Karachi Biennale 2017, site size: 45ft x 85ft. Courtesy Tazeen Qayyum. Photo: Mahmood Ali.

“Growing up I was not scared of the cockroach,” Tazeen Qayyum tells me.

We are sitting in her large, light-filled Oakville home—a house large enough for she and her partner, artist Faisal Anwar, to set up a project space in it for other artists, whether ones based in this quiet suburb, or ones travelling from her home country of Pakistan, where she was born in 1973 and graduated with a degree in Indian miniature painting in 1996.

Qayyum’s studio is on the second floor, down the hall from her daughter’s room. There are plants and shells about, and a drafting table, and Nirala Sweets tins that hold some of her supplies. Occasionally, the light glints off her thick black Marc Jacobs glasses as she speaks, or motions to an image on her computer screen.

In one pic on her screen, hundreds of cockroaches cut out of red paper climb up the outside of the Jamshed Memorial Hall in Karachi in her 2017 work Facade. Then there’s a 2015 installation from the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa—hundreds more cockroach cutouts, these ones in red acrylic and arrayed in a circle eight feet in diameter, called Infiltration.

And then there’s the work for which she is best known: many, many carefully executed miniature paintings of cockroaches: cockroaches decorated and undecorated, cockroaches painted and outlined with a single-hair brush, painted and stuck with pins or splayed in grids of red thread.

“I think the motif has been there since 2002,” Quayyum reflects of what is now, pretty much, her hallmark insect. “The very first time I used it was when the US started the first invasions on Afghanistan. At that time I was back in Pakistan and the migration [to Canada] was in process.”

She adds: “Initially, I just repeatedly painted a dead bug.”

Tazeen Qayyum, Observe and Release , 2009. Opaque watercolor on wasli (prepared archival paper), 26.5 x 23 cm. Permanent collection, Robert McLaughlin Gallery Oshawa. Photo: Faisal Anwar.

Tazeen Qayyum, Observe and Release , 2009. Opaque watercolor on wasli (prepared archival paper), 26.5 x 23 cm. Permanent collection, Robert McLaughlin Gallery Oshawa. Photo: Faisal Anwar.

Going back and forth between Pakistan and Canada as a self-identified “brown Muslim” in those early days of the US invasion of Afghanistan meant “I experienced it in both cultures—I experienced the attacks from Pakistan and how the media was presenting it here.”

She pulls up another image on her laptop screen—a 2007 Columbus Dispatch editorial cartoon by Michael Ramirez. It depicts Iran as a sewer drain and Iranians as cockroaches creeping out of it, some of them into Pakistan. A different JPEG pops up, this one of a news item in Huffington Post UK: “Muslim women confront Exeter man who says Muslims are ‘Cockroaches Invading’ UK.” It’s from 2016.

“The main idea for the cockroach has always been the idea of fear—how something you don’t understand” can become feared, Qayyum says. “The cockroach itself is not the most dangerous insect around us—yet it is universally considered gross.”

It’s not a far jump, then, from considering that insect to thinking about way humans think about “cultures we don’t understand, or that have ideas we do not agree with,” says Qayyum. “There is this fear, this labeling.”

From her first cockroach painting in 2002 onward, then, Qayyum has countered that fear with beauty, using a single-hair brush to depict cockroaches (even if dead) with beautiful floral patterns on their exoskeletons, or arraying them in neat grids.

Then, in 2013, her cockroaches escaped off the canvas. Invited to do a piece in a vitrine at Toronto Pearson Airport’s Terminal 1, she filled the vitrine with a neat array of red cockroach cutouts, and called it Holding Pattern.

“The reason I called it Holding Pattern is because that’s the lingo that is used whan a plane is not allowed to land. When it has to go in circles,” Qayyum says. “And I feel that is making a connection with the whole political situation.”

In front of the installation, she put an airport-lounge chair painted over with flowers—a gesture, perhaps, to those who control the mobility of others, or those who are so privileged as to not experience any contraints on their desired migrations.

“The pattern on the chairs is derived from traditional Mughal paintings,” Qayyum says. “I’ve used it many times in other my work as well; it signifies royalty or power.”

Tazeen Qayyum, A Holding Pattern (detail), 2013. Site-Specific, Mixed Media Installation at the International Toronto Pearson Airport, Terminal 1. Courtesy Tazeen Qayyum. Photo: Faisal Anwar.

Tazeen Qayyum, A Holding Pattern (detail), 2013. Site-Specific, Mixed Media Installation at the International Toronto Pearson Airport, Terminal 1. Courtesy Tazeen Qayyum. Photo: Faisal Anwar.

Eventually, Qayyum’s explorations of a single insect, the cockroach, and of that single insect many times over, led her into a new territory—the portal or void.

In the mid 2000s, Qayyum started to appropriate entomology conventions into her paintings of dead cockroaches—using the stickpins and tagging terminology of the science to translate “how many casualties were reported, what weapons were used, what cities” were associated with U.S. bombings in Afghanistan.

“I think that’s where the circles started coming in initially,” Qayyum says, “as zooming in or seeing through something magnifying—petri dishes and museum displays and that sort of thing.”

More recently, she started becoming interested in the manhole and gutter system in Karachi.

“I wanted to remove the cockroach image for my new show,” Qayyum says. “I am actually going into the manholes, into the gutter—so the essence of the bug is here.”

The manhole form dovetails with the circular writing performances Qayyum started doing in 2013, inscribing words and phrases from her native Urdu language and poetry until a substrate was filled with text.

“It is a self-exploration in a way, when you repeat one phrase repeatedly,” Qayyum says. Some of the phrases she has worked with relate to fears of religious intolerance. Others are pleas for forgiveness. Yet others question the differentiation between good and evil. These are all phrases with great gravity, phrases that pull an artist down to earth—and sometimes, down into earth.

“I want to recreate these manholes,” says Qayyum of her new work at Canvas Gallery. “But related to that whole idea is a desire to actually write the text over such multiplicity that from afar it looks like a black hole.”

Tazeen Qayyum, Blur (video still), 2015. Single channel video, 22 minutes. Courtesy Tazeen Qayyum.

Tazeen Qayyum, Blur (video still), 2015. Single channel video, 22 minutes. Courtesy Tazeen Qayyum.

It is compelling to consider the great facility Qayyum has for precision—a facility she is now, if not outright rejecting, at least deflecting.

“Until 2007 or 2008 the references were very much from attacks on Iraq—but now narrative has widened,” she notes.

Her old aesthetic “goes with the medium I’m trained inminiature painting. The idea in miniature painting is everything has to be precise and clean,” says Qayyum.

Now, however, there’s her decision to let the paper cockroaches installed outdoors in Facade simply decay along with their water-based glue. “I’ll make the disintegration part of the work as well. There is no deinstall,” Qayyum explains.

Her increasing engagement with circular drawing performances also suggest a letting go. “You are in the circle, blindly getting into something—not thinking, just following,” Qayyum says of those works.

And in videotaping herself drawing on the body for Blur, a different kind of opening is also at hand.

“That is the first time I’m putting my vulnerability out there in a certain way,” says Qayyum. “Since I can remember I have been putting [kohl] in my eyes – even before I leave my bed in the morning.”

To centre this new body of work, to centre the void, and vulnerability, and process in the face of the success Qayyum’s past miniature-painting-style, cockroach-focused work enjoyed, well, it can read as a risk. A risk worth taking.

“A narrative of helplessness is there,” Qayyum says of the new work. But she also adds, before we part: “Self discovery happens in phases where you are not comfortable.”

“Tazeen Qayyum: Descent” continues until March 1 at Canvas Gallery in Karachi.

This post was corrected on February 26, 2018. The original copy erroneously noted a smaller diameter for Qayyum’s Infiltration, as well as misstated the source of some of Qayyum’s texts.