Note to the reader: I am using this monthly column to think out loud, in public, about questions and controversies arising from my current research for a book about contemporary Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995.

Earlier this year, I was at an event where an artist of Indigenous heritage said that non-Indigenous ideas are dangerous to Indigenous people and that we ought to stay away from them. I’m paraphrasing, but that’s the gist of it.

The statement got my attention for a number of reasons. As someone researching a book on Indigenous art, I am grappling with how to approach and make sense of the material I am gathering. In other words, I am worrying, as academics say, about which methodologies I will use.

Different approaches can lead to dramatically different results. For example, if I was to follow the advice to avoid non-Indigenous ideas, that would certainly radically shape the outcome. Likewise, if I did not consider the various Indigenous intellectual heritages that inform the work of many of the artists and writers I will be studying, that would also have serious consequences.

Also, two colleagues—Heather Igloliorte and Carla Taunton—have invited me to present a paper at a symposium they are organizing this October at Concordia University called Theories and Methodologies for Indigenous Art in North America. That has got me thinking as well. (It will be a public event with many interesting people presenting; if you get a chance I’d recommend checking it out.)

So is there an Indigenous way (or ways) to write about art? Could it be an exclusively Indigenous way? I hope it doesn’t give too much away if I tell you the working title for my symposium paper is: “Muddling Through: A Case for Methodological Diversity in Writing About Contemporary Indigenous Art.”

Now I believe that it is true, in a very narrow sense, that non-Indigenous ideas are dangerous. This is just because all ideas are potentially dangerous. The best way to manage that danger is to experience a diverse range of ideas and cultivate the ability to engage them deeply and critically. Bracketing off whole cultures worth of ideas has the paradoxical effect of making people more vulnerable to bad thinking rather than less, because the bad ideas just sneak in the back door anyway. Note, for example, the ubiquity of 19th-century race theory in hardline Indigenous nationalism. Every time someone inquires after a person’s blood quantum, for example, their concern for racial purity paradoxically demonstrates the internalization of the very worst aspects of colonial ideology.

Also, in purely practical terms, how would you bracket off Indigenous culture? Where would you draw the line? No more pop culture? How about all of the postcolonial critiques of colonial representation? Indigenous authors have been involved in that discussion, but so have many others. How could we untangle which bits are “ours,” and what help would it be to do so?

In my experience, the best writing about contemporary Indigenous art has always demonstrated the intellectual agility to meaningfully combine and use all sorts of methods, theories and ideas originating from a variety of cultural backgrounds. It would have to, to keep up with the range of approaches and content in the art.

And if we are willing to be honest, we can acknowledge that we do not have an existing set of traditional Indigenous art-historical methods to simply take down off the shelf, so to speak, and put to use. If art is, as the legacy of institutional critique has made so clear, an institutional practice, then most of the institutions that give form to our contemporary practices—art schools and universities, galleries and museums, books and magazines—are all without direct precedents in our traditional cultures.

This does not mean that we do not have rich artistic, intellectual and institutional heritages to draw on of our own, just that it requires critical rigour to understand if, when and how to deploy these resources in the various contexts of the contemporary art world.

Another challenge is that many of the Indigenous intellectual traditions that might be relevant were brutally interrupted by colonialism and then reconstructed, at times rather clumsily (and all too often with a pan-Indian New Age patina), in the 1970s revival of Indigenous cultures. This means that accessing traditional thought can, at times, be a hermeneutically challenging undertaking requiring the ability to critically parse both historical texts and contemporary oral narrative to arrive at a convincing interpretation.

I think this methodological diversity is being practiced across Indigenous academia, even in very radical texts. When Glen Sean Coulthard argues, in Red Skin White Masks, that Indigenous peoples should stop seeking political recognition from colonial states and recognize themselves, he does so by drawing on the theory of two non-Indigenous revolutionaries, Karl Marx and Frantz Fanon. He needs those ideas to help him make sense of the situation he is analyzing. Likewise, when Cathy Mattes writes an essay called “Winnipeg, Where It All Began—Rhetorical and Visual Sovereignty and the Formation of the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc.,” she concludes her argument for cultural sovereignty with a quote from the German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer.

This is not a phenomenon particular to Indigenous scholarship. It has been decades since a single methodology has dominated art writing in general, and it is common for writers, even those who align themselves primarily with particular approaches, to draw on a wide range of methods in their work. Someone who defines their writing generally in terms of a commitment to decolonial theory, might in practice find themselves using everything from the traditional staples of art history, such as visual analysis and biography, to Marxist, feminist or postcolonial theory, to name but a few.

In fact, there are so many cross-cultural influences and such diversity of approaches in an art world (and broader culture) that is now in many senses global, that it has become increasingly difficult to assign ownership of particular approaches exclusively to a particular cultural tradition. The question should not be, “Which tool is properly ours?” but rather, “Which tool works for the job at hand?”

So why do we sometimes talk about Indigenous cultures as something we can neatly bracket off from other cultural influences? I think it is a colonial trap that is sprung at the intersection of salvage anthropology and certain strains of Indigenous nationalism. It is a trap that preys on both our anger and trauma at being colonized and our anxieties that, after all, we do somehow lack traditional authenticity.

The immediate response to forced assimilation is almost certain to be a desire to preserve what is under threat. But if we do this unreflexively—making the tradition its own justification and our only duty to mimetically reproduce it—we risk perpetuating our own lack of agency by systematically deferring to an idealized past. This can inhibit us from deploying ideas from our intellectual heritage into new contexts where they might live with more vitality.

If we want to be Indigenous in the present, we need all the tools available to us. And the courage to use them.

Richard William Hill is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Studies at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver. If you have advice, information, documents or anything else that might help him with his research on Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995, he would be grateful to hear from you: richardhill@ecuad.ca. Thanks to the many people who have already been in touch.

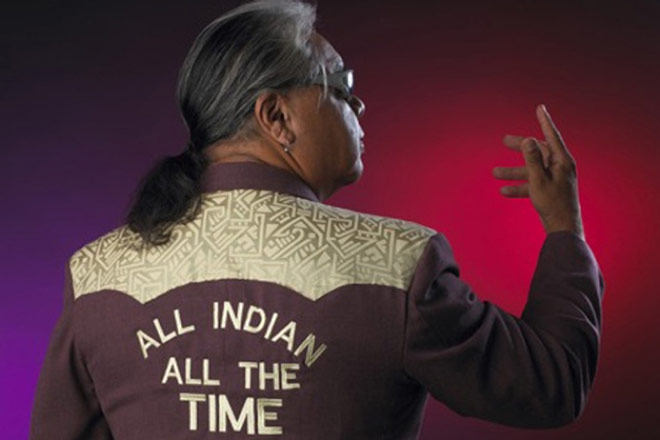

James Luna, All Indian All the Time (detail), 2006. Photo: William Gullette.

James Luna, All Indian All the Time (detail), 2006. Photo: William Gullette.