Black creative works often make me speechless. For this reason, I try to think about Black creative art or Black visual art or Black music as an intellectual interlocutor with Black studies theories—I try really hard not to privilege theory over the creative text, but rather to have them in conversation. And so that’s sort of a radical interdisciplinarity—a bringing together of different texts and textures and sounds and hues, and seeing how they, in tandem, provide a different and unexpected methodology for Black life and joyousness.

What you also notice, of course, is that often the Black creative text is more interesting and more innovative than the theory. It’s a lot more fun, and also—particularly with music or visual art—it helps you experience what you cannot say, or what cannot be textually expressed. How Black people relate to each other in plantation and post-plantation contexts, within systems of oppression, matters. These creative texts help us relate to each other…they insist on a language of imagination and fun and sadness and friendship and heartbreak that is not totally indebted to or enveloped by systems of oppression! How we relate to each other matters and how we tell each other stories matters because the stories are often embedded with codes and clues about how to live this world ethically. And so for me part of that storytelling is through music and music-making. The wonderful thing about music is the groove; it is always the groove. You can listen to Sade and just be like, “yeah,” and you don’t have to say anything, you can just sort of be in love with it.

Sylvia Wynter’s wonderful 900-plus page document, Black Metamorphosis, which is housed at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, points to this idea about the politics of music. It was written in the 1970s and notices that the politics of expression and the politics of music are very significant to how Black people imagine a world outside of racial capitalism and racial violence—she’s not the only one who does that, but I find her argument particularly compelling: she shows that the way we relate to each other, creatively and otherwise, is an expression of our humanity. But it’s not just a generalized humanity, it’s a humanity that is outside white supremacy. And I think that’s exciting and that’s what joy is and that’s what pleasure is. It’s knowing the world differently and living the world differently as you’re navigating a world that despises Black people. —As told to Yaniya Lee

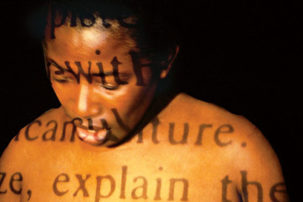

Martine Syms, Incense Sweaters & Ice (still), 2017. Digital video, 69 min. Courtesy the artist/Bridget Donahue, New York.

Martine Syms, Incense Sweaters & Ice (still), 2017. Digital video, 69 min. Courtesy the artist/Bridget Donahue, New York.