We were a small group from the École des beaux-arts de Montréal—two men and three women: Fernand Leduc, Pierre Gauvreau, Louise Renaud, Madeleine Desroches and me—and we would talk about how academic the teaching was and how we wanted to be more free. We met at Paul-Émile Borduas’s atelier on Mentana Street on a November evening in 1941, and it lasted until almost 4 a.m. Bruno Cormier would have been there also, but he had studies to do. It was an amazing encounter. After Borduas showed us his first abstract “gouaches,” he introduced us to André Breton’s Le Château étoilé, and to surrealism. We were stunned; he opened up a whole new world, to which we had aspired. He seemed to show us a way to be more free. And that was the beginning of les Automatistes.

I always wanted to be an artist, so being a woman didn’t seem to be such an obstacle. It feels right for me to be an artist. I like what I do. I strive to work hard to do good work. Men don’t stop doing what they do if they have a family. It’s life. So I didn’t see why I should stop. I could do a lot of things. I thought, well, sculpture is close to painting: it’s about form, and you make it. I liked it. I worked in my garage, took some welding courses, got equipped and worked for about 10 years like that.

But then something shifted in the art world. There was talk about art not being interesting. People kept on doing art, but they disparaged it. That disturbed me very much; I couldn’t take it. All the writing was talking this way, saying, for instance, that we didn’t need museums anymore. So, okay, no museums, no art. So what could I do? I just reacted. I thought, I’ll go see what’s outside. I’ll walk between two museums, from one to the other [for the 1970 work Walk between the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Fine Arts (Promenade entre le Musée d’art contemporain et le Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal)]. It was quite a distance. I took my camera, left from the museum, and took a photo at every corner of the street, making no aesthetic decisions. I’d come to another corner, take the photo, and so on. It was a long walk on a scorching August day, which is why we see very few people on the streets. But it turned out to be a good piece.

After a while you sort of get into the mindset of conceptual work. If there was an idea, then you had to find a way to do it. And that was difficult too. If you paint or do sculpture, you know what your tools are, but with conceptual work you had to invent ways of doing it. You take a chance, and you do it. If it’s good, great; if it’s not…well, you just leave it. But usually it worked. It was a completely different way of thinking. If you are painting, you paint every day. And sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s not, but you continue until it becomes something. With conceptual art, there was nothing—just ideas, thoughts. That was very hard, very demanding. But I did some and it seemed to work—I mean, we still show them! —As told to Yaniya Lee

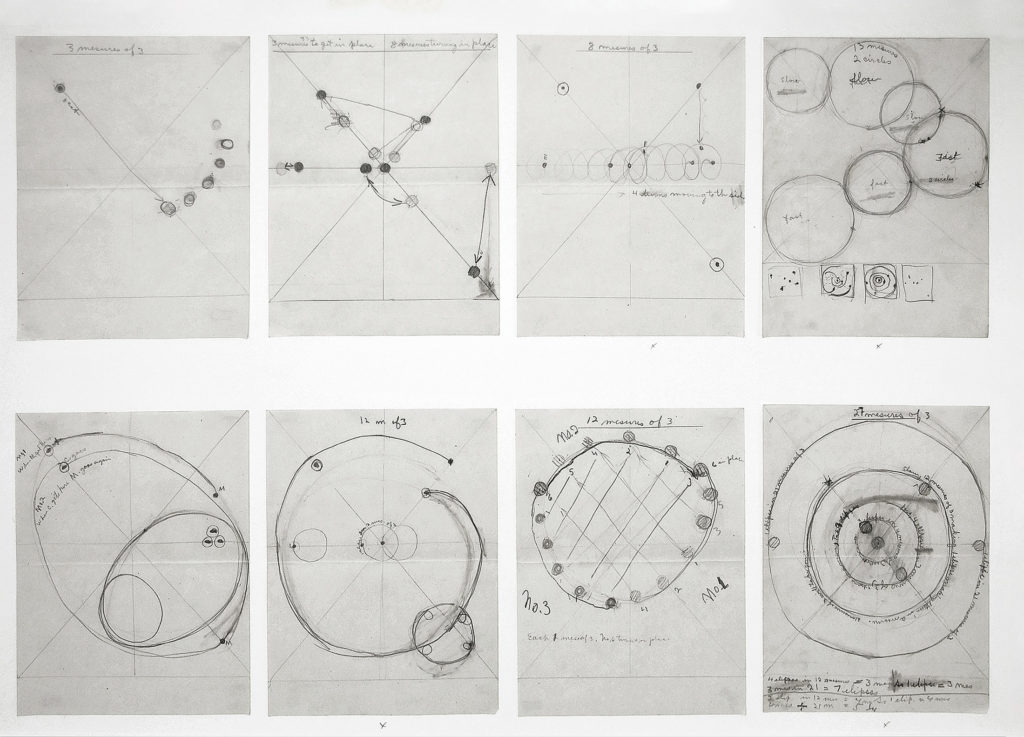

Françoise Sullivan, Dance notations for Les Planètes, ca. 1945. Graphite on paper, 64 x 83.5 cm overall. © Françoise Sullivan/SOCAN (2019). Photo: Galerie de l’UQAM.

Françoise Sullivan, Dance notations for Les Planètes, ca. 1945. Graphite on paper, 64 x 83.5 cm overall. © Françoise Sullivan/SOCAN (2019). Photo: Galerie de l’UQAM.