MONTREAL Deep winter, 2010. It’s teeth-rattling bitter in Montreal, so the talk in Françoise Sullivan’s atelier in old Pointe-Saint-Charles turns to the intertwined arts of painting and toughing it out. Both are much on our minds because her ancient heating system, now wheezing and rattling loudly, gives evidence of being in its mechanized death throes. Our main source of warmth is the recent paintings that lean against the patchy workspace walls.

Each “almost monochrome,” as Sullivan describes these large canvases—most are five by six feet—is as formally conceived as a Cézanne apple turned belly up in the Mediterranean sun. Yet the works—with their feathery-edged horizontal planes in buttery yellows, orange-gold or woodsy black—also suggest ideas that exist only at the threshold of consciousness: the idea of heat, say, not heat itself. I imagine Mark Rothko channelling the effect of Bonnard’s colour. “I don’t think these paintings are sad,” Sullivan says. Sad? They’re as radiant as state- of-the-art solar panels.

The building she’s in, a hunched-over one-storey affair with an off-kilter door, adds to the chill. “It looks like an old monastery,” I tell her.

Sullivan moves with only slight hesitations, looks terrific in form-fitting jeans and has earned just about every award her country grants its artists, including a 2001 appointment to the Order of Canada. Her lipstick is bright, her blue eyes even brighter. She’s had this studio for almost a quarter of a century.

“I am the monk,” she tells me.

As the world re-rediscovers Sullivan—as it does about every decade (along with re-renewed promises never to forget her again)—it’s inevitably reminded of her singular importance to Canadian painting and sculpture, to Canadian dance and to Montreal’s Automatiste movement and the publication of the Refus global in 1948 (she signed the manifesto when she was in her early 20s). A lightning bolt across the grande noirceur of Maurice Duplessis’s corrupt, poor and priest-ridden Quebec, Refus global created a political furor when it appeared. The Automatiste ringleader Paul-Émile Borduas was sacked from his teaching job at l’École du Meuble as a result. With its inclusion of Sullivan’s essay “La danse et l’espoir,” the manifesto’s subtle feminist subtext could not be ignored, either. “Remember there were nine men and seven women who signed,” says Sullivan today. “So there was equality. There never was a war with the men. I just had to prove that I was a good artist, an important artist.

“I always knew I’d come back to painting,” Sullivan goes on. “But I went through a terrible crisis in the 1970s when all the theorists were saying painting was dead. I was shaken. I went to Italy to discover Arte Povera, which was supposed to be replacing painting. But I didn’t like anything I was doing. It felt as if the world was falling apart.”

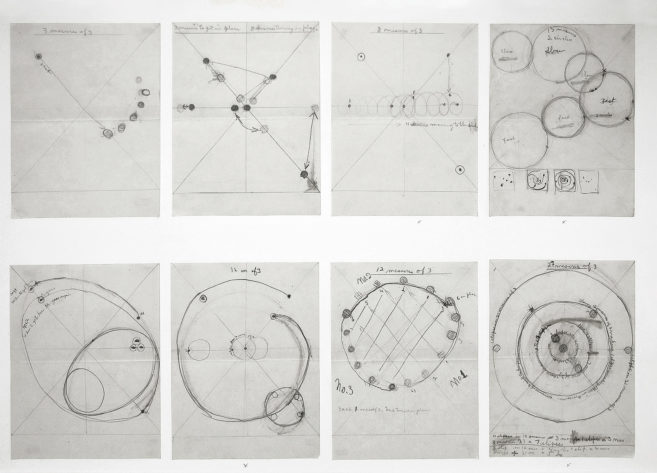

Sullivan returned to painting in the late 1970s and soon produced her Tondo series: bravura, muscular assemblages that marked the inception of her synthesis of dance and painting and asserted, as she puts it, that “my dance thoughts are painting thoughts.” In Dédale— Sullivan’s groundbreaking 1947 dance piece, which is accompanied only by the solo performer’s increasingly laboured breathing—the dancer enacts a trauma of bodily convulsions, starting with barely perceptible motion in her fingers. “A painting is a movement of thought,” she says. “I was acting on instinct with those dances, as well as intellectual research akin to Automatiste thought. I’d just come from studying dance in New York to my studio and my Automatiste principles. These dances were the equivalent of the paintings being done at the same time by the [Refus global] group.”

An awareness of image-making was also central to Danse dans la neige, the series of dances she improvised on a frigid February day in 1948 across patches of rain-hardened snow in Mont-Sainte-Hilaire. The filmed record of the event—shot by Jean Paul Riopelle using Sullivan’s father’s 16-millimetre camera—has since disappeared. All we have are Maurice Perron’s black-and-white photographs, which are typically as much a part of every Sullivan exhibition as her painting.

“I knew what I would look like,” she says. “I told Riopelle where to stand. Perron stood shoulder to shoulder with him. I was very aware of where I was standing in the landscape, where I’d be and what the images would look like. And in spite of this, there was something quite magical about the moment. The inspiration came very much from the site.”

From February to May, 2010, the Art Gallery of Ontario held a show of Sullivan’s work in conjunction with the $25,000 Gershon Iskowitz Prize she was awarded in 2008. Yet Sullivan’s shiny AGO moment was somewhat compromised by a concurrent exhibition, “The Automatiste Revolution: Montreal 1941–1960,” which was expertly organized by Roald Nasgaard and appeared at Buffalo’s Albright-Knox Art Gallery last spring after opening at the Varley Art Gallery in Markham. Sullivan feels Nasgaard’s show was “beautiful, with the best paintings”; some observers felt that “The Automatiste Revolution” should have been at the AGO and not in the Toronto suburbs.

Looking back at that crucial moment in the Automatiste period, Sullivan now remarks, “Refus global was something I could not back out of, like painting itself, or dance. I was frightened for my father [John A. Sullivan], who was a member of the Catholic School Board. I didn’t even tell him I’d signed it.

“He came home one night. He’d found out. He’d been approached by the president of the Catholic School Board, who had the [Refus global] book. ‘Is this your daughter?’ he’d asked my father.

“My mother [Corinne Bourgouin] was calm. They loved each other. They had a good relationship. ‘Come on,’ she said to my father, who was angry—all that Irish blood. ‘This is our daughter.’ I never heard about it after that.”

This is an article from the Fall 2010 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.