I grew up between France and Algeria—two countries whose histories are very heavy in terms of colonization, though it took me some time to develop the concept of repair that I would eventually explore in my work. First, around the 1990s, I began to focus on the more humble, traditional processes of repair, one aspect of which really struck me: when we look at old artifacts that have been repaired according to traditional methods—say, a mask that has been broken during a ritual, or a calabash—the injury of the object is still visible because the way it has been fixed was very rough. There is the physical and material necessity to fix the broken object, but also, despite the imperfections, somehow the repair itself has been done in a way that produces its own aesthetic.

This opened up a reflection on why traditional societies have always considered the injury—the cracking or breakage—as a significant narrative, whereas in the modern Western mind the approach to fixing an object is to believe it can be restored to its original form as best as possible. If a car is in an accident and you have to replace a broken door, for example, you find a matching, identical one. But in traditional societies and poor societies where people cannot afford what the modern West calls the perfect repair, they just find another door from a similar model, but they won’t paint it red to match the car. I like this. It made a strong philosophical impression on my research about repair, and within my own ongoing reflection about how to understand the world we are living in, and these endless processes of domination by the most powerful civilizations over minorities.

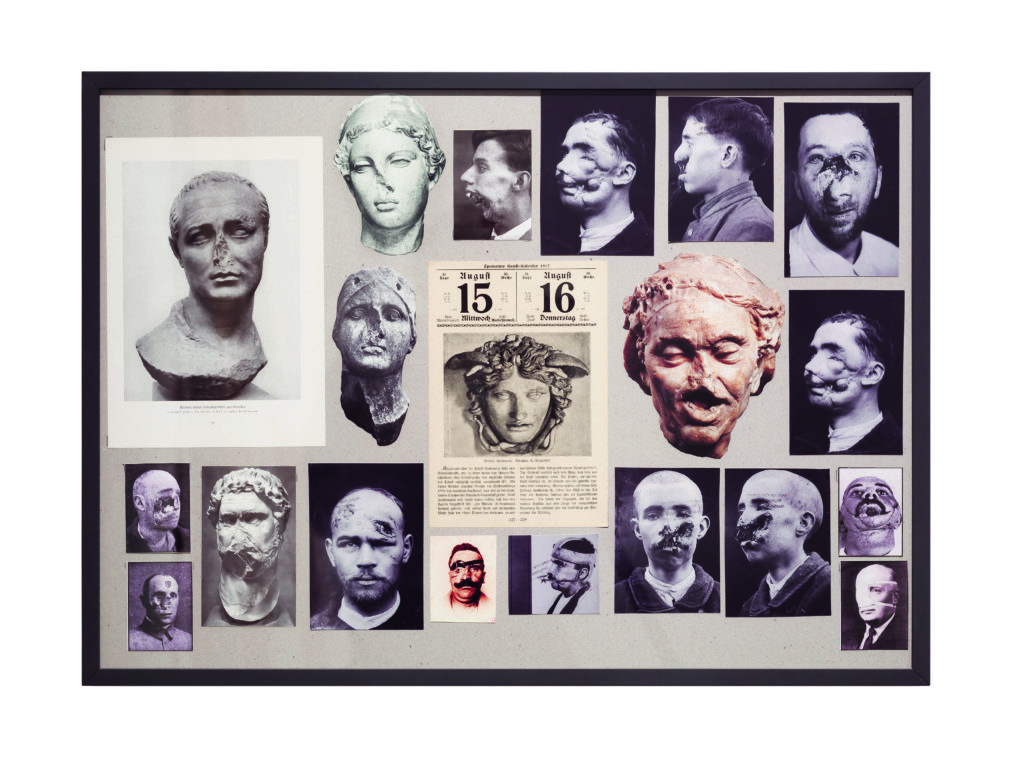

In light of how traditional societies tend to highlight the injury, thereby giving the object a second life in which the injury is part of its re-enactment, I quickly went from the broken item that has been fixed—the broken glass, the broken mask, the broken calabash, the broken chair—to wondering whether these sorts of dead objects could be compared with human bodies. The modern Western world has been following these blind ideas where repair means to bring back the original shape of the object before it was broken. This pertains to the human body too. During World War I, a very significant moment in the history of modernity, when the faces of soldiers were injured—called in French gueules cassées, or broken faces—it became the stage for science’s struggles between the Germans, the French, the British. They competed in restoring the original shape of these injured soldiers’ faces.

After doing a lot of research in French and German museums, I discovered that the scientists of that time were indeed obsessed with repairing human bodies. And to do so they asked for the help of artists and sculptors, bringing art into the arena of science. If half of a soldier’s jaw was missing, they asked a sculptor to create an artifact of a jaw then had the nurses paint it to match the patient’s skin colour. For example, there are these prosthetics made out of resin, which the soldier had to attach every morning with a string. To me it’s fascinating because it demonstrates how much Western modernity is based on illusion and delusion. It illustrates the agenda of modernity and its Promethean promise—the promise of power, of weapons, technology, sciences, which is the way that the colonization of Canada happened.

—As told to Merray Gerges

Kader Attia, Untitled,

2014. Cardboard, paper,

photographs and graphics from old books,

50 x 70 cm. Courtesy

Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna. Photo: Axel Schneider.

Kader Attia, Untitled,

2014. Cardboard, paper,

photographs and graphics from old books,

50 x 70 cm. Courtesy

Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna. Photo: Axel Schneider.