Art institutions are well aware of how easily shifts to arts funding—boosts or cuts—can affect the climate for the production and presentation of culture. Historically, one solution to the absence of Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) curators and administrators has been through temporary curatorial residencies and grants geared toward them. But how can such programs —which unwittingly draw attention to the otherwise naturalized absence of BIPOC from gallery curatorial and management offices—ever fully address the ongoing structural exclusion of BIPOC arts professionals from the leadership and creative positions that define contemporary culture through this country’s institutions, if they’re dependent on funding moods?

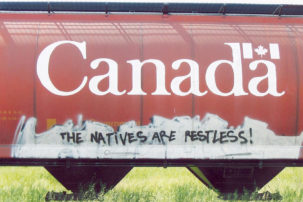

Curators and other gallery programming and management staff are often thought of as somehow inherently fluid and always contemporary. They are expected to initiate discourse and the engagement of broad constituencies and areas of concern. This is not the case with BIPOC curators and administrators, who are frequently assumed to be competent or relevant only in connection to their identity and culture, and often given space to work only within that context. The specificities of when and on what terms BIPOC curators are invited to do projects are models for the state’s management of difference, and were evident in the language and mandate of programs that attempted to engineer cultural diversity through one-to-two-year relationships between BIPOC curatorial residents and a host institution. We can trace this back to such important but flawed initiatives as the Canada Council for the Arts’s now defunct Grants to Culturally Diverse Curators for Residencies in the Visual Arts and Grants to Aboriginal Curators for Residencies in the Visual Arts. In each case, the inclusion and exclusion of often marginalized voices in visual and curatorial practices can be linked to the shifting environment at the Canada Council.

How and where was it normalized to restrict the parameters of concern, experience and knowledge for BIPOC curators in Canada? This needs to be known as it is the basis for what obstructs access to curatorial and senior positions in galleries and art centres. It is also what limits the majority of BIPOC participation and presence in galleries and gallery programming to topical and temporary engagements. The research and anecdotal observations of curators like Andrea Fatona, Sally Frater, Michelle Jacques, Michael Maranda and Jordan Wilson help to shed light on this. Through my questioning, they reveal how the ecology of contemporary art centres and galleries in Canada balances on, and responds to, the specificities of a climate composed of cultural policy and funding priorities set by public agencies such as the Canada Council. Jacques, Frater and Wilson suggest that access to mentorship, professional networks and material resources can be at turns moderated or emphasized through conscious efforts on the part of institutional stakeholders at various levels. What’s noted by these curatorial and gallery professionals is the limited capacity of grants, targeted at diversity, to change or open up the working environment to curators and gallery stakeholders of Indigenous and racialized backgrounds on a basis that is more than temporary or exceptional.

Having a diverse staff is necessary not only for how it can affect programming, but also how it allows for the ability of such staff to pressure the institution from the inside.

Fatona’s overarching historical research, “‘Where Outreach Meets Outrage’: Racial Equity at The Canada Council for the Arts (1989–1999),” traces the increase and decrease of supportive and productive periods at the Canada Council, connecting funding trends to outside factors and pressure in correlation to shifts in government policy and spending cutbacks. She shows that widening and narrowing definitions of contemporary art and official culture—as a tool of cultural and social exclusion in the name of nation building—governs the ebb and flow of BIPOC curators and other arts professionals.

Fatona dates this back to the 1951 Massey Commission, which was developed in response to lobbying by intellectuals and artists for the creation of a funding agency to support art and academic activity. The generally white and male appointees to the Commission had outsized influence on establishing a cultural Canadian-ness, beyond their individual positions as middle-class intellectuals. This modelling on a Eurocentric imaginary was inherited from the Massey Commission’s and Massey Report’s mid- 1950s formulations of cultural patronage that responded to a desire among that era’s Canadian cultural elite to “imagine and produce discourses, practices, and narratives of the young nation as white, modern, and European,” Fatona writes. It was within this mindset that the Canada Council for the Arts Act of 1957 established the public funding agency.

The outcome of these parameters for measuring official Canadian culture caused a severely troubling paradigm of multiculturalism that marginalized the cultural production and limited the funding opportunities for communities that were already pushed to the edges of the nation’s social, political and economic periphery.

Fatona explains that funding for ethnocultural groups was connected to capacity building and the showcasing of “cultural products and performances of ‘other’ ethnic groups who were not French, English or Aboriginal.” This essentialized the cultural production of many artists, making racialized and Indigenous artists perform their difference, while affirming the dominance of European-derived traditions, forms and aesthetics. It’s this institutional appropriation and consumption of cultural difference—rather than the creation of open paths to holistic and supported inclusion—that leads to a ghettoed participation of BIPOC arts professionals.

“We can see that visible-minority and Indigenous populations in Canada have been increasing over the last 20 years, but gallery-management diversity is lagging behind even 1996 numbers,” curator Maranda found when he examined demographics from census data since 1996, and surveyed 80 galleries across Canada in 2017. In a quantitative report published in Canadian Art in April last year, Maranda found that the presence of visible minority or racialized individuals in director, curator and other gallery programming and management roles was disproportionately low given the percentage such individuals make up in Canada’s artist and general population, and in connection to groups that have more access to resources. Maranda rightfully describes the situation for Indigenous management and programmers as “distressing.”

Installation view of Raimi Gbadamosi's SWADSQUAD (2006) and SINGULARLY AMBIVALENT (2006) at Novas Gallery, London, UK. Photo: Raimi Gbadamosi.

Installation view of Raimi Gbadamosi's SWADSQUAD (2006) and SINGULARLY AMBIVALENT (2006) at Novas Gallery, London, UK. Photo: Raimi Gbadamosi.

Short-sighted and half-hearted funding and recruitment-based gestures toward diversity and inclusion lead to the telltale presence of the single curatorial intern, resident or contractor of colour or Indigenous background. Despite stated proclamations to the contrary from institutions, the feeling of limited support and belonging that these situations engender is, in my experience, unshakeable. The presence of other BIPOC staff at these galleries would have indicated that a sincere process of inclusivity and reflection was actually being implemented in the institutions concerned.

Sustaining structural diversity is at the heart of Sally Frater’s concern: institutions often rely on grants for internships and limited residencies

to temporarily increase staff diversity, but this short-term inclusivity doesn’t carry over into hiring when vacancies for permanent gallery, curatorial or management staff open up. Frater is an independent curator who recently worked in the Modern and Contemporary Art department of the Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State University and currently curates at Centre[3] for Print and Media Arts in Hamilton. She acknowledges that programs like the Canada Council for the Arts’s Culturally Diverse Curator Grant were important to supporting emerging curatorial practices and helping grant recipients to realize ambitious projects. But she also observes that such situations, which temporarily parachute in racialized and Indigenous curators, should be seized upon by institutions as encouragement to create paths toward broad diversity across board and staff positions. Frater advises that, “If individuals who are committed to diversity and inclusion are either hired/appointed, that is usually reflected in the programming that institutions present, but [it] also begins to trickle down to their staffs as well.” Art organizations need to reflect and represent the diversity of their sector and community at all levels, and this requirement should lead them to seek out “individuals who will both benefit from as well as enrich the programming and operations at these institutions.”

For Frater, it is crucial for board members and employees who are not used to working with racialized, LGBTQIA individuals and people with disabilities to receive training as part of a long-term strategy—rather than a brief intervention for change—and this is the sustainable way to create climates that support the thriving professional and creative practices of Indigenous curators and curators of colour.

The self-reflection and planning around inclusive staff and board succession that Frater calls for should be extended to post-secondary education where studio art, critical and curatorial departments and degree programs should train students, whether or not they self-identify as racialized, Indigenous or LGBTQIA, to expect to work in—as well as create—diverse and inclusive working environments.

Rather than essentializing exclusionary cultural hierarchies and categories, art spaces and institutions must engage in reorganizational shifts.

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria chief curator Michelle Jacques echoes Frater’s concerns about the limits of grants supporting diverse presence with minimal influence on the culture or thinking in host institutions. Jacques recalls, in our email correspondence, how, when she was an assistant curator at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Richard W. Hill got one of the first Canada Council grants for Indigenous curators, in 2000. His temporary position transitioned into a full-time post as a curatorial assistant, and Jacques assumes that this was one of the all-too-few instances where such grants expanded into a permanent job.

Having a diverse staff is necessary not only for how it can affect exhibition programming, Jacques points out, but also how it allows for the ability of such staff to pressure the institution from the inside when principles meant to address diversity and transparency are developed and implemented.

Furthermore, questioning the prevalence of expertise and mainstream academic paths to gallery and creative leadership at art institutions is important, and Jacques sees the particular conditions and assumptions about curatorial positions in Canada as shifting the conversation on training, and also the definition of curatorial work. She highlights the increased community outreach/inreach that is expected of curators in Canada compared to their American counterparts. “Even in collecting institutions, in Canada, the emphasis [on] what a curator needs to know moved away from connoisseurship long ago, and curators who have expertise in engagement actually have an edge,” she writes. “If the engagement needs to happen in culturally specific communities, the ability to gain entry, speak the language, overcome barriers, etc. is a new kind of curatorial expertise, and organizations that recognize this will have the advantage.”

To counter the institutional will toward temporary and limited power-sharing, the key for curator Jordan Wilson is that BIPOC curators are able to transform whatever institutional access they may attain to enable broader inclusion through community-centric rather than individual-led thinking. The risk of excluding Indigenous people and people of colour from positions of decision-making, for Wilson, is that it might exacerbate such absences beyond curatorial roles and in the entrenched systems of collecting and education, which can’t simply be addressed through a few occasions of diversity in programming.

As director at an artist-run centre in Vancouver, I have realized that the volunteer oversight of boards of directors can also be an influential way to counter—or at least address—the need to raise up and empower BIPOC communities and a generation of racialized and Indigenous arts professionals. An enduring climate that could alter structural exclusions from decision-making and power-sharing can’t be established if any level of institutional function is excluded from the process of diversification. This includes every level, from board members to staff members. Jacques allocates this responsibility to an institution’s governance; she asserts that “the aim must be to ensure that the board is the keeper and conveyer of visions of inclusivity so that they see it as absolutely essential that diverse candidates are interested in working with them.”

Rather than essentializing exclusionary cultural hierarchies and categories, art spaces and institutions must engage in reorganizational shifts that refuse to marginalize the cultural impact, engagement and leadership of racialized and Indigenous arts professionals, creators and collaborators in all areas. This is simply what’s required for institutions to stay relevant—to the communities who are asked to support them and who wish to see themselves reflected within them.

A previous version of this text mistakenly described chief curator Michelle Jacques as “director and chief curator” at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. It has since been corrected.

Raimi Gbadamosi, SWADSQUAD (detail), 2006. Three-person chess game installation; wood, plastic, paper and paint, dimensions variable. Photo: Leela Axon.

Raimi Gbadamosi, SWADSQUAD (detail), 2006. Three-person chess game installation; wood, plastic, paper and paint, dimensions variable. Photo: Leela Axon.