In 1940, Canada’s Department of National Defence opened a munitions factory along Mississauga’s waterfront. The Small Arms Limited Building would supply rifles and small arms to the Canadian Army through the Second World War, and was operational until 1974. It’s the sort of space now canonized in cultural memory for its employment of thousands of women amid changing gender roles in Canadian public life, both during and following the war. After gaining heritage status in 2009, the factory was restored as the Small Arms Inspection Building (SAIB) and in 2018 it opened as a multi-purpose site for arts and cultural programs, combining the functions of a community space and an art gallery. What is a heritage building if not a site recognized for its cultural significance to national identity? What does it mean when heritage is part of a war effort? The production of munitions is a settler state’s cultural inheritance in the same way that a gallery is a space intimately tied to histories of nation building.

Almost 80 years after it was first occupied by women workers, the Small Arms Inspection Building issued its new mandate: to “provid[e] access to underserved community members who are living with disabilities, are Indigenous or racialized, or self-identify as 2SLGBTQ+,” namely in the form of exhibitions and public programs. That a place can carry forward its history so lucidly is remarkable. If, in the 1940s, the women of the munitions factory were invited to participate in new nationalisms through their labour, today this invitation is mirrored in updated nationalist fantasies of “multiculturalism” and “diversity,” as articulated in publicly funded art structures throughout Canada. If we think of the former factory as a site of labour continuous with the present, today that labour takes the form of artists and cultural workers operating within the identity categories prescribed by funders and related arts structures. There are many ways a factory becomes a metaphor for an art gallery.

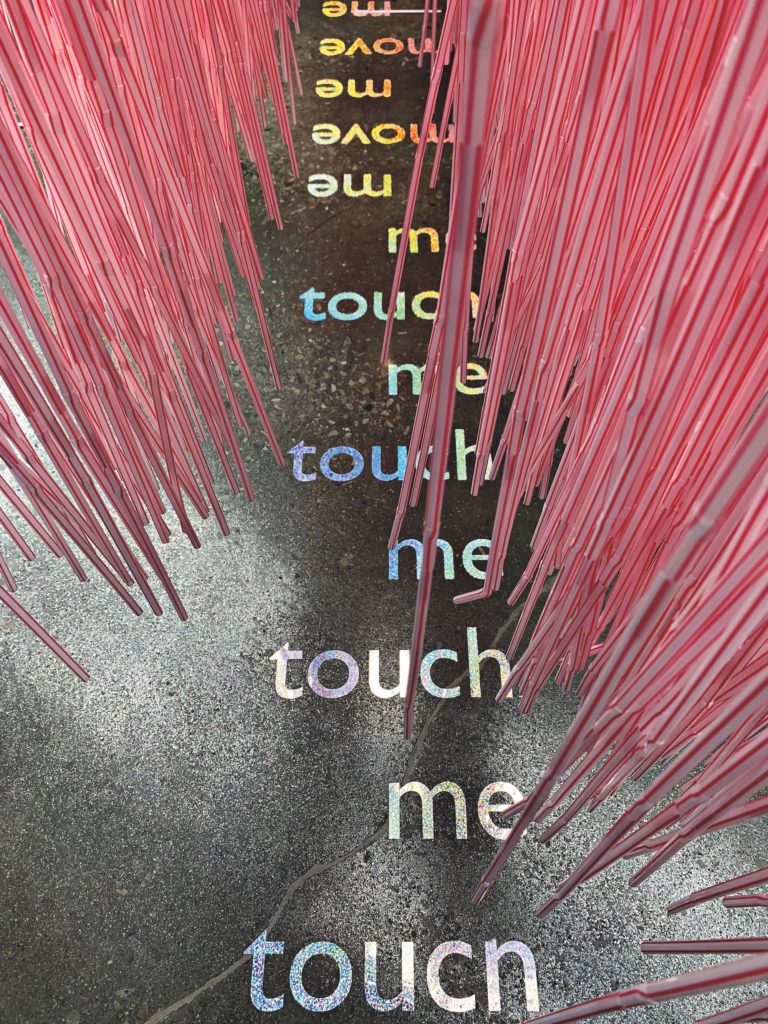

A recent group show—“Public Volumes,” curated by Noa Bronstein—engaged the former factory’s history through the lens of spatial justice with works by Joi T. Arcand and Kara Springer (among others) that looked “to the tangled means by which we defend the spaces that offer support and the efforts we take to transform those that fail.” The show included jes sachse’s Freedom Tube, a sculptural installation composed of thousands of the iconic red-and-white-striped drinking straws. Produced as part of an ongoing series, the sculptures repurpose the classic straw by assembling thousands of them into large hanging sheets. Here jes makes visible the quotidian, everyday objects so familiar to disabled lives. Of the installation process, they tell me, “The straws are threaded into a curtain, one by one, at a rate of about 500 straws per hour.” The assembly of Freedom Tube occurs across many hands and conversations, with this invited care compensated by way of a shared artist fee, to honour the collective and regionally site-specific installation process. For “Public Volumes” this collective included Safia Abdigir, Noa Bronstein, Hannia Cheng, Nadine Forde, Petrina Ng, Sanchari Sur, Emmie Tsumura and Elizabeth Underhill. With this labour occurring in the former factory space, jes’s installation process commented on another type of labour frequently required of the artist: bad-faith calls for representations of disability. If the gallery is a factory, for jes, its violences are “felt and carried in the body.” As an artist, they’re responding to demands to be further looked at when already hypervisible. The form of jes’s sculpture figuratively obscures the gaze upon their own body with the use of purposely anticlimactic household objects and references. The straws and the curtain gesture not to easily legible signifiers of physical disability, but to its more quotidian, everyday aspects—here imbued with so much care. “The straw becomes a network of straws, one for every coffee you drink, one for every daily adjustment needed to make [our] bodies ‘fit,’” jes says.

Mundane acts of daily life…offer useful strategies for living through ongoing violence. Larger acts of protest would not be possible without these quieter instances of refusal.

I am reminded of 2017: I tuned in every week to a livestream of jes’s performance/protest To be Frank, in which they pushed a wheelchair across the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Walker Court, over and over again. It felt as exhausting as a lifetime of being incommensurable with the gallery. But a lifetime can hold instances of everyday refusal just as much as it can bear out the everyday labour of access. Freedom Tube blows up what goes unnoticed—the straw from breakfast, the straw from dinner—to proportions so large that an audience is forced to reckon with it. In this, jes’s practice is in conversation with a wider tradition of writers and artists who engage at the level of everyday life, or as gender studies scholar Ann Cvetkovich has termed it, “the utopia of everyday habit.” Mundane acts of daily life (“I took my meds,” “I ate something today”) offer useful strategies for living through ongoing violence. Larger acts of protest would not be possible without these quieter instances of refusal. In this way, the mundane bleeds into and begets the exceptional. Freedom Tube, with its thousands of plastic straws, is preoccupied with how lives persist in contested spaces, spaces where power may permeate and regulate but not preclude practices of living that might elude the state—from queer kinship to unpredictable networks of access and care. Something new arises in the mundane violence of the everyday, as we find other modes of being in the world through the imperfect acts of living.

The materiality of Freedom Tube places it in conversation with disability justice and ecofeminist discourses. An earlier iteration of the project at Regina’s MacKenzie Art Gallery, for instance, was contemporaneous with growing public debates around the environmental impact of plastic straws. jes noted that a year after that installation, “A&W would mark their transition from plastic to paper straws with a large sculpture at Toronto’s Union Station, branded as ‘the last straw.’” In this greenwashing gesture, thousands of plastic A&W straws were assembled to spell out “Change is good.” What does it mean to ethically condemn the use of plastic straws with no discussion of alternatives for the disability communities that rely on them? What is at stake when we frame large-scale environmental damage (itself a result of centuries of settler-colonial and extractive capitalist processes) as an individual choice still invested in market? Again, we return to the image of the factory, as if to say: the market can falsify its claims to save the planet as easily as it purports to manufacture diversity. Now that the exhibition at the Small Arms Inspection Building has ended, what will happen to the plastic straws? They will all be recycled, turned into furniture and donated back to the building so that, eventually, visitors will be able to sit on a trace of the former sculpture, traversing the space between art and the everyday.

jes sachse, Freedom Tube (detail), 2019. Installation with straws, text and vinyl at the Small Arms Inspection Building. Courtesy the artist.