I have always loved the story of the Chris Burden’s performance at the Alberta College of Art in 1976. Burden was invited to produce a commissioned work at ACA (recently renamed the Alberta University of the Arts, or AUArts, and formerly the Alberta College of Art and Design) by then-curator Ron Moppett and assistant curator Brian Dyson of the school’s gallery. Burden had already gained notoriety in the California performance art scene for works that put his own body in extreme situations, in particular Shoot (1971), a now iconic piece where the artist had someone shoot him in the arm with a .22 rifle. The performance at ACA, titled Do You Believe in Television?, began with Burden lighting a trail of straw on fire along the darkened stairwell connecting three levels of the parking lot adjacent to the college. Television monitors were installed on all three levels and approximately 100 audience members lined up and down the stairs to watch a static live feed focused on a black tape cross stuck on the ground floor, while smoke gradually filled the stairwell. As Moppett remembers it, “You could stand there and believe in television or you could get out of there.” By the time the fire trucks arrived Burden was already on his way to the Calgary airport escaping possible arrest.

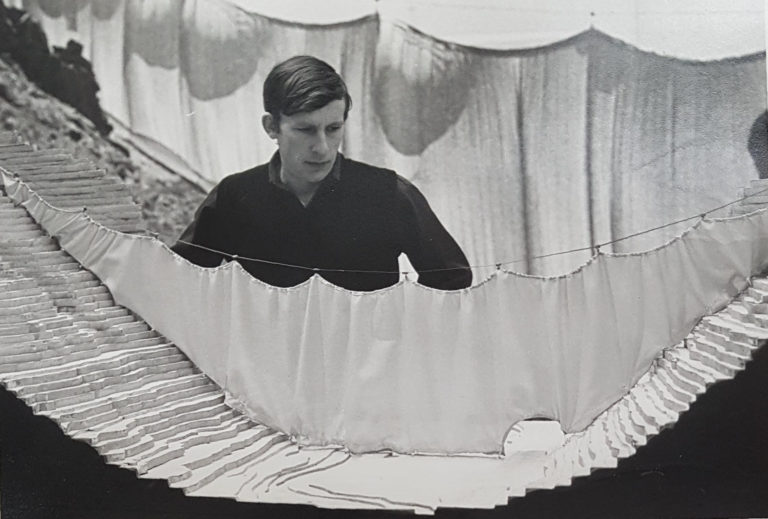

Alberta College of Art Gallery curator Ron Moppett at Christo’s “Rifle Valley Curtain Documentation," December 1–21, 1975.

Alberta College of Art Gallery curator Ron Moppett at Christo’s “Rifle Valley Curtain Documentation," December 1–21, 1975.

In an article in artscanada two years later, Paul Woodrow describes the Alberta College of Art Gallery as providing “the most sizable contribution” to the recent development of art in Calgary through its quality and diversity of programming. This included not only major exhibitions of works by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Robert Rauschenberg, Lee Friedlander and Dennis Oppenheim, but also parallel series of workshops and artist talks by the likes of Willoughby Sharp, General Idea and Michael Snow. “The gallery’s policy is to serve the needs and interests of the students of the college as well as the community at large,” notes Woodrow, “and this has been accomplished through an insistence by the curatorial staff on organizing their own exhibitions, rather than accepting many traveling shows.”

Influential exhibitions would continue through to the 2000s at the then-renamed Illingworth Kerr Gallery (IKG) with shows including artists such as Iain Baxter, Carl Andre, David Hockney, Liz Magor, Laurie Anderson, Attila Richard Lukacs, Guerrilla Girls, Faith Ringgold, John Baldessari, Annie Pootoogook, Iran do Espírito Santo, Janet Cardiff and Paul P., to name just a few. Still, it’s hard to imagine Burden’s performance happening at the college today. When I asked Moppett, who was curator and later director/curator of the gallery until 2005, as well as an instructor at the college since the early 1970s, how he was able to make it happen, he explained: “I didn’t have to salute a gallery committee so there was an immense amount of trust which I received, which I appreciated. Also the budget was real, and in the city there was an appetite for seeing really important contemporary art.”

The IKG’s recent exhibition “Unpacking IKG: 60 Years a Gallery” endeavoured to document the gallery’s notable history through an exhibition of its archive and permanent collection. The curatorial process is described in the exhibition didactics as a literal unpacking to invite “participatory analysis and examination.” The exhibition included the gallery’s crates and file boxes alongside a timeline and a selection of videos and posters related to past shows and programs, as well as works from the permanent collection and a research space for students. Gathering together the IKG’s holdings in a cohesive way is an enormous and impossible task in itself. Prior to this show, exhibition files were never properly archived, while the gallery’s collection, which has never had an acquisition mandate, is made up of a mishmash of past gifts from faculty and visiting artists. The show was conceived by IKG curator Lorenzo Fusi, who upon his departure from the college in January 2018 left the planning to the gallery’s curatorial intern, Ashley Slemming. Without a curator in place, Slemming sought the mentorship of craft histories professor Jennifer Salahub from AUArts’ Faculty of Critical and Creative Studies, who advised on and supported the exhibition process. Salahub’s research interests in institutional history, notably, are also part of her own project: writing a history of craft in Alberta by looking at the histories of AUArts, with the hope of developing the college into a centre for excellence of craft in Canada. Together Slemming and Salahub spent months culling available materials to amass a chronicle of gallery’s history, which up until that point had not existed.

The premise of “unpacking” is in itself problematic, since a curator does not merely discover contents and neutrally display them, but instead hails an entire colonial narrative of history and ideology in their process of selection and display.

The result was an exhibition and accompanying catalogue that describe the IKG through the lens of the college, and that fold too easily into the services of institutional promotion at the same time that the provincial government officially granted ACAD university status in March 2018. “Unpacking IKG” collapses the history of the gallery with ACAD’s, locating its beginnings in 1916 with the founding of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, before there was even a gallery space, let alone an independent art college. The overall focus of the show is on the developments of the college, and how the IKG’s formation as a gallery worked in the service of the school’s curriculum and developing international reputation, with minimal analysis of its key exhibitions from the 1970s to today. For example, an entire history of the gallery under the curatorial direction of Wayne Baerwaldt—from 2005 to 2015—is simply described as a socially engaged approach that put the white cube “under attack,” while the gallery shifted to “representing cultural diversity.” Putting aside the problematics of this language, opportunities to explore (or even mention) key IKG shows during Baerwaldt’s tenure were missed, such as Glenn Ligon’s 2009 exhibition, which included the seminal video installation Death of Tom (2008), originally commissioned and produced with students at the college and now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In the absence of adequate historical documentation—and with a necessarily patched-together curatorial organization—it is understandable that the exhibition had some shortcomings. What is concerning here is how the history is being written as a result. The premise of “unpacking” is in itself problematic, since a curator does not merely discover contents and neutrally display them, but instead hails an entire colonial narrative of history and ideology in their process of selection and display. This particular issue is amply demonstrated in the selection of objects from the collection that includes paintings by canonized Albertan artists such as Illingworth “Buck” Kerr and Maxwell Bates alongside what are described as “objects” (rather than artworks) from the incongruously categorized regions of “Tanzania, Africa, South-West America, Peru and Arizona,” and which are left unattributed and undated. Presenting this as a matter-of-fact display of the collection’s shortcomings does not acknowledge the museum as a colonial enterprise, nor do any program offerings invite critical dialogue around issues of representation in the collection, gallery’s programming history or college at large. Artist and AUArts associate professor Justin Waddell has raised concerns to the school administration about the exhibition’s lack of diversity and representation of Indigenous histories in the show’s timeline, didactics and selection of works. “As an instructor my concern is the way that students feel represented in the institution,” he told me. “I can’t speak on their behalf, but as a faculty of colour I can say that I don’t feel represented.”

So what is really going on here? A close look at the programming of any art school gallery will generally provide a measure of its health. The issues of this exhibition are not the fault of any one person, but instead a symptom of the college’s lack of support for the gallery in recent years. In 2015 Baerwaldt was encouraged to take an early retirement when he was informed by administration that, through a “restructuring process,” the college was planning to dissolve the director/curator position. After Baerwaldt’s departure, that position was revised to “Visiting Academic Curator,” a limited-term annual appointment reviewed by AUArts administration each year based on funding availability. Filled briefly by Fusi from 2016 to 2017, this appointment would leave advance-programming budgets in an untenable situation since exhibition cycles typically require at least two years of planning to make time for grant application processes. In an interview with AUArts president, Daniel Doz, about the IKG and its curatorial position, he explained: “For a few years we’ve been in budget-cut mode quite regularly. Calgary got hit by a recession so donations to the arts slowed down quite drastically.” Since Fusi’s departure from the gallery last year, the IKG has been without a curator, and programming gaps in the next year will be filled by unsolicited exhibition proposals. By not ensuring a stable curatorial position at the gallery, the college has failed to provide critical curatorial knowledge to oversee IKG programming and thus key issues and problems around ideologies of display in an exhibition like “Unpacking” are missed.

The position of Visiting Academic Curator advertised in September 2018 outlines that the incumbent is to assist in the future development of the IKG in becoming “more inclusive and representative of the variety of programs at the college…to support future academic growth.” Upon the news a year ago that ACAD’s university status request was going to be moved forward, Doz explains that the college looked at how to better integrate aspects of the institution and build a stronger research framework, which included moving the IKG under the umbrella of graduate studies to better support the curriculum. According to Richard Brown, AUArts director of research and graduate studies, the new curatorial position will be a faculty post, which will help make a “transformation” to the gallery by allowing for the individual to have input at various academic levels, a closer relationship to the schools and faculty and better access to internal granting opportunities. As outlined in the gallery’s 2017 Strategic Plan, developed in part by Brown, the curator will report once a semester to the college’s Research Advisory Committee (a faculty-driven group) to “coordinate, review, and receive council on gallery exhibitions and public programming, capitulation of degree, curriculum, long-term planning and programming goals, and to asses the outcome of completed goals.” For Brown, the logic of keeping the job as a limited-term appointment (now extended to a four-year term) is to “understand…the fit now between the IKG and the other curricular areas of the school. So it gives us a chance to really test this out before we commit to a full faculty position.” Doz also explains that the advertised curatorial post “is really embedded in the academic enterprise much more closely than what it was in prior years. Really it’s not to dictate what the research agenda is but it’s to offer the IKG as a potential support line…when needed. So the exhibit that we currently have, which is ‘60 Years A Gallery,’ is another example of research.”

Installation view of Theo Sims’s The Candahar (2010/2012) at the Alberta College of Art and Design's Illingworth Kerr Gallery, February 2–May 26, 2012.

Installation view of Theo Sims’s The Candahar (2010/2012) at the Alberta College of Art and Design's Illingworth Kerr Gallery, February 2–May 26, 2012.

The overwhelming benefits to students and faculty of a university art gallery program being integrated into the school’s core academic agenda have been well cited by numerous studies. As assistant curator at the IKG from 2011 to 2013, I witnessed the potential of the gallery as a space of activation, particularly when collaborating with the artist Theo Sims to organize talks, and performances in his installation The Candahar (2010/2012), a replica of a Belfast pub installed in the gallery that functioned as a working bar, and when working with students on Calgary’s first Nuit Blanche in 2012. These programs engaged ACAD’s community in artistic production and critical dialogues on contemporary art, with students later telling me it was their experience through the gallery that gave them the tools to become practicing artists. In furthering research the gallery does more than merely represent an internal curriculum or offer the college support, as suggested by Doz—it engages students in direct experiences with artworks and artists, valuing art as a method of research in itself. Creative research was something the IKG had been doing well before talk at the college of new academic frameworks and the dissolution of the director/curator position. In my conversation with Baerwaldt, he points out that the research role of the gallery is also about looking to both the strengths and the deficiencies of the curriculum, which is what he sought to do with exhibitions such as Ligon’s in 2009, as well as with the conference “Stronger Than Stone: (Re)Inventing the Indigenous Monument” in 2014, which addressed ACAD’s long-standing lack of diversity and encouraged Indigenous teaching to strengthen learning opportunities.

While the written commitment made by AUArts to the gallery through its strategic plan is a positive step, strengthening its capacity for research requires much more than lip-service and a “pilot position,” and includes a certain amount of autonomy, engaged support from faculty and administration and a healthy budget to deliver exhibitions. When I asked Baerwaldt about some of the challenges during his tenure, he pointed to a severe lack of funding that placed the institution in crisis and led to the gallery being seen as a financial burden whose exhibitions were not part of the core curriculum offering. There were even discussions at the time of using the Glenbow Museum as a possible gallery for students to engage with objects if the IKG were to close and the space used to expand administrative offices and graduate student studios. On an extensive 2013–14 IKG Review and Report for the college, Baerwaldt recommended that integrating the position of curator into the college as a faculty position would give students space in the curriculum to engage with the gallery, offer the curator a recognized voice as an academic research person and provide security to the gallery’s operations that would be protected by the faculty association. In our conversation about IKG’s new strategic plan and curatorial position that takes from his report, he is cautiously optimistic: “It’s a good thing the way they are going—if they are truly going to respect that and honour that.”

Think back to Moppett’s comments about what made the gallery’s infamous Burden performance possible: trust, money and community support. Autonomy within the institutional structure of an art school requires an advisory committee that trusts an embedded curator to determine the gallery’s program. A healthy budget is one that sustains both operations and a robust exhibition program. As for support, this is not offering up the gallery’s space, staff or budget to the chopping block when times are tough, but rather truly committing to it as a necessary place of research. Rather than looking to transform the gallery into an apparatus that will “support internal activities,” administrators and faculty must recognize that the IKG has long provided an essential place of learning. AUArts needs to implicitly support the IKG as a propositional space where artists, curators and students can experiment and take risks outside of academic structures and engage in critical thought through art and exhibition making. In our classrooms, we continue to talk about Burden’s 1976 pyrotechnics, even though the college’s new health and safety committees would never sign off on such a project today. The lesson is that artistic research comes in many forms—and that even the riskiest experiments are well worth witnessing.