Dayna Danger

The first time I laid eyes on Nico Williams’s beaded ball-gag I was smitten. Drawn into my own topping fantasies centred on sovereign Indigenous sexualities, I felt seen and validated. Williams’s beaded ball-gag turned me on in ways that had been locked inside me for centuries, when Two-Spirit identities were erased with the onset of colonial gender binaries and repressed sexualities. When I first saw Silenced No More, and witnessed Indigenous-specific desires and sexuality represented in the gallery, I felt seen and represented. I was pulled into my innermost femme-dom fantasies.

Tiny red beads, clutching each other tight, bound by a thin thread.

Tight in your mouth, glistening saliva.

The floral patterns of our ancestors wrapped around your head, gripping and hugging you.

When you’re this loud, you need something BIG to shut you up.

Two-Spirit peoples, our sex and our place in society were erased by the colonizer’s histories. But “silence no more” means that our genders, sexualities and ways of loving will never be suppressed, and Indigenous-specific, desire-coded revolution is possible. Healing colonialism means we can be whomever we want, even if that being is bound and gagged, with a beaded ball-gag, to muffle cries of pleasure. Two-Spirit peoples will never be erased, and neither will our powerful and persisting sexualities.

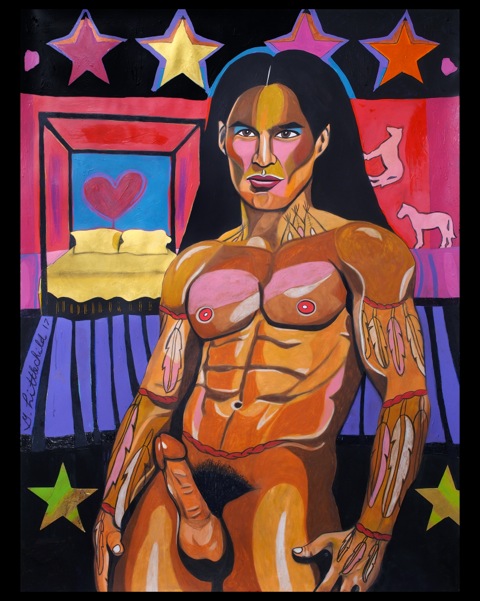

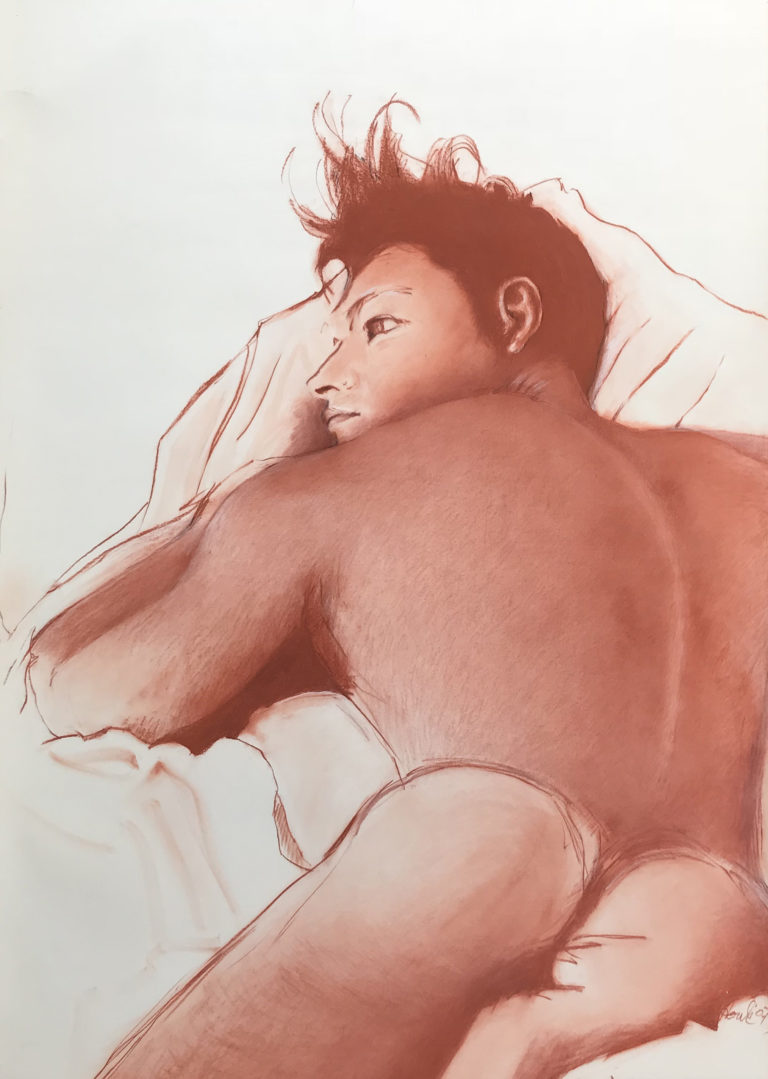

Adrian Stimson

In 2017, I curated a Two-Spirit exhibition for the Queer Arts Festival in Vancouver called “Unsettled.” While all the works “turned me on,” two in particular stood out: Robert Houle’s drawing Untitled (2007) and George Littlechild’s painting Cree Boy Thrust (2017). After placing all the works, I realized that the trickster in me had placed Robert’s work across the room from George’s, giving them a pitcher-and-catcher sexual inference. Part of my intent in curating these two works was to address the absence of representation of Two-Spirit art and being from contemporary popular culture. The legacy of colonialism was to, ultimately, erase our bodies, our beings and memory from time. These two works tickled me, not only in the loins but also in the head, because as we know, eroticism happens in the mind. For me, the works deploy artistic and critical discourses that focus on Two-Spirit resilience. They give presence where absence existed; they liberate, they dissimilate; they expose bodies and beings for all to see and imagine. They turn us on to art that addresses power, representation, sexuality, language, body, tradition, memory, Indigenous story telling and knowledge sharing. For me, you can’t get sexier than that.

George Littlechild, Cree Boy Thrust, 2017. Mixed media, 127 x 96.52cm. Courtesy the artist.

George Littlechild, Cree Boy Thrust, 2017. Mixed media, 127 x 96.52cm. Courtesy the artist.

Robert Houle, Untitled, 2007. Conté and chalk pastel on bond paper, 177.8 x 127cm. Courtesy the artist and Kinsman Robinson Galleries.

Robert Houle, Untitled, 2007. Conté and chalk pastel on bond paper, 177.8 x 127cm. Courtesy the artist and Kinsman Robinson Galleries.

Althea Thauberger

I have been fortunate to witness/participate in a number of Skeena Reece’s performances, and I count as them some of the most profound experiences I’ve known. They are historically, psychologically and politically brilliant, not only because of what she says, sings and enacts, but also because of what she helps us feel, together. We become hyper-aware of our relations and of our subject positions, varied as they are. As a performer and leader Skeena is at once intimidating and vulnerable, and she makes us receptive of how to be better. As Sandra Semchuk said after Skeena’s performance with Jeneen Frei Njootli, There is time for love (2016) at the Audain Gallery in Vancouver, “This is some powerful medicine.”

Skeena Reece, There is time for love, 2016. Performance at Audain Gallery, Vancouver. Courtesy SFU Galleries. Photo Blaine Campbell.

Skeena Reece, There is time for love, 2016. Performance at Audain Gallery, Vancouver. Courtesy SFU Galleries. Photo Blaine Campbell.

Luanne Martineau

To John Berger, glamour is a modern system/symptom of industrialization, capitalism and failed democracy. Something similar can be said for “sexiness” and “sexuality”—but Fafard’s bronze contemplations of bull balls and cow udders offer transcendent overlap within this Euler diagram. His balls and udders are commodities in a traditional sense, produced and reproduced in limited edition. Painted representations of the land baron’s livestock become fully realized forms for purchase and display within a collecting culture removed from agrarian life. His balls and udders “give” themselves to the pornographic nature of photography, while simultaneously refusing the camera and its proliferated image on the experiential level. Highly rendered and absolutely abstract, Fafard’s balls and udders are enigmatic. While surface appearance and proportion are compliant to anatomical function and are imbued with ancient and contemporary associations of sex and power, their materiality rejects both lines of understanding. The internal structures, contents and mechanisms that dictate external form are absent; the visual trompe l’oeil of malleable pearls encased in sagging flesh is revealed to be hard and unyielding, and the desire to cut into and finger the slippery contents of deliciously full fertility only reasserts their absolute unknowability.

Joe Fafard, The Pasture, 1985. Seven bronze sculptures, Toronto Dominion Centre. Photo Bryne McLaughlin.

Joe Fafard, The Pasture, 1985. Seven bronze sculptures, Toronto Dominion Centre. Photo Bryne McLaughlin.

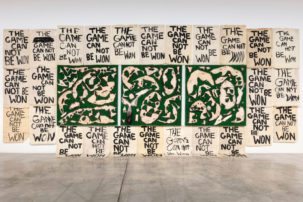

Luis Jacob

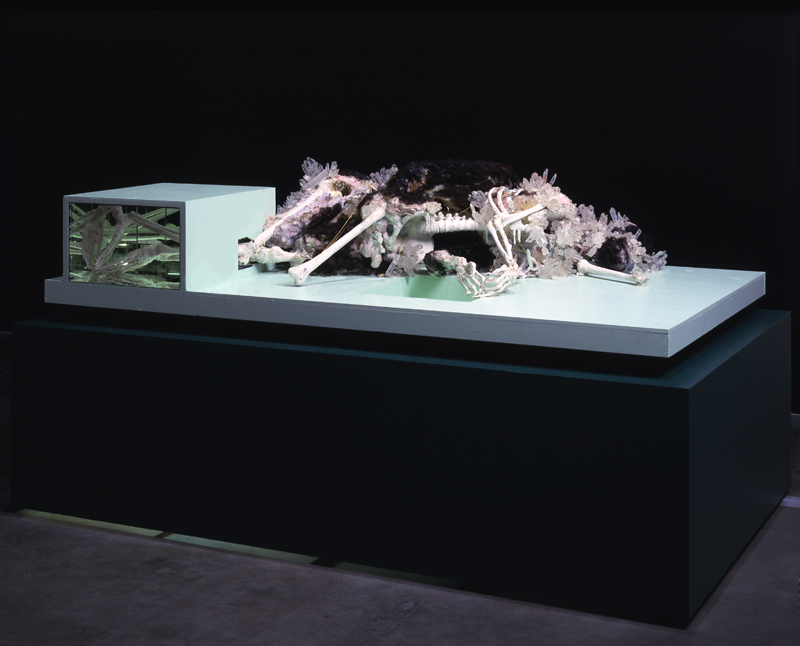

David Altmejd once gave an artist talk during his exhibition at Oakville Galleries in 2007. Standing around a sculpture titled The Lovers (2004), viewers asked about his use of decoration, the contrast between organic and geometric forms and the meaning of the crystals growing out of the two figures that compose the work. With each new question, I grew increasingly frustrated and impatient. Finally, I asked: “Has anyone ever asked you about the fact that the sculpture depicts two hairy creatures fucking?” Pondering for a moment, the artist replied, “No, I don’t think anyone has ever asked me that.”

The experience taught me something about conservatism in the art world. I learned about intelligent, well-educated people and their adoption of a formalist language as a way to foreclose discussions of desire and sexuality. I wonder what it feels like for Altmejd’s lovers to fuck in such a stifling context.

David Altmejd, The Lovers, 2004. Plaster, resin, paint, synthetic hair, jewelry, glitter, wood, lighting system, Plexiglas and mirror, 1.14m x 2.28m x 137.16cm.

David Altmejd, The Lovers, 2004. Plaster, resin, paint, synthetic hair, jewelry, glitter, wood, lighting system, Plexiglas and mirror, 1.14m x 2.28m x 137.16cm.

Jessie Short

Is it strange to say that Dayna Danger’s 2017 video Bebeschwendaam turns me on? I mean, it’s a beautiful video of two gorgeous women (the artist and her friend Parneet) who are mostly naked, covered in oil, and wearing two moose antler racks on their pelvises, attached by strap-on harnesses. The video cuts between shots of Dayna and Parneet’s faces, gazing into each others eyes as they reflect on their interactions and laugh, and shots of their pelvises, locking horns, thrusting, trying to overpower one another, and finally of them spooning while standing, rocking gently as one. It’s tough and tender, revealing and concealing. The depth of their intimacy with each other, as much as their nudity, touches me deeply and boils my blood at the same time. But I hesitate to admit this because I consider both Dayna and Parneet to be friends, and it seems counter to social norms to admit in a public forum that I’m attracted to the work and, therefore, to my friends. I think, however, this is not counter to Bebeschwendaam or to any of Dayna’s work, which is based on the relational, ongoing negotiation of the privilege and power of portrayal, constructed within a safe space for all involved. And that is a major turn on.

Dayna Danger, Bebeschwendaam, 2017. Video still. Courtesy the artist.

Dayna Danger, Bebeschwendaam, 2017. Video still. Courtesy the artist.

Lili Huston-Herterich

Dear Cecilia,

I think about how to edge up mountains—building stimulation and retreating before climax, weaving between their trees, teasing their tree lines, feeling their companion winds push me toward the summit, before turning back and repeating again. Your works transcend the temporality of objects. I read your poetry and your voice like a companion wind, it carries me. I return to Vaso de Leche. A glass of milk is tipped by a red wool string; the photograph’s frame holds me tight and the shadow tells me the milk is about to spill. I am looking closely. The performance undoes itself in its becoming.

I read that in 1979 merchants in Bogotá added poisonous paint to milk to increase profit. The spill happens in the street, a quiet occupation of space, a dizzying vertigo between a horizonless plane and the perpetual flow of a body’s fluids. Foreplay, between a forest ground and a summit vista. You show me how to look closely, so we can look further.

Love,

Lili

Cecilia Vicuña, Vaso de Leche (detail), 1979. Site-specific performance, Bogotá, Colombia. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul. Photo Oscar Monslave .

Cecilia Vicuña, Vaso de Leche (detail), 1979. Site-specific performance, Bogotá, Colombia. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul. Photo Oscar Monslave .

Nico Williams, Silenced No More, 2015. Beaded ball-gag and antlers. Courtesy the artist. Photo Judith Brisson.

Nico Williams, Silenced No More, 2015. Beaded ball-gag and antlers. Courtesy the artist. Photo Judith Brisson.