In mid-October, in Tourcoing, France, near the Belgian border, an exhibition of video from Canada’s Arctic, called “Une lumiere blanche” (A White Light), opened the fall exhibition season at the new media school Le Fresnoy. Along with other exhibitions involving video, CD-ROM projection, camera obscura and film/sculpture installation, all of them loosely related through their response to landscape, “A White Light” included nineteen videotapes produced over ten years by Inuit artists from Igloolik, a small settlement on an island resting between Melville Peninsula and Baffin Island.

It is a landscape familiar to few outsiders. The link to it, for Le Fresnoy, National Studio of Contemporary Arts, was exhibition programmer Pascale Pronnier. Pronnier and I met in Toronto in 1990, when she worked on an exhibition of contemporary art from France at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Afterwards, she joined the planning team for Le Fresnoy, and when she heard of the Igloolik work being prepared to tour Canadian museums in 1999, she immediately signalled her interest. Pronnier had seen some of the tapes in France and elsewhere, and, even before the shows could be launched back home, she promptly confirmed an opening date in France.

The works are unique, hovering between contemporary drama and historic documentary: material never before seen, yet familiar all the same. A classic dream made actual. Timeless.

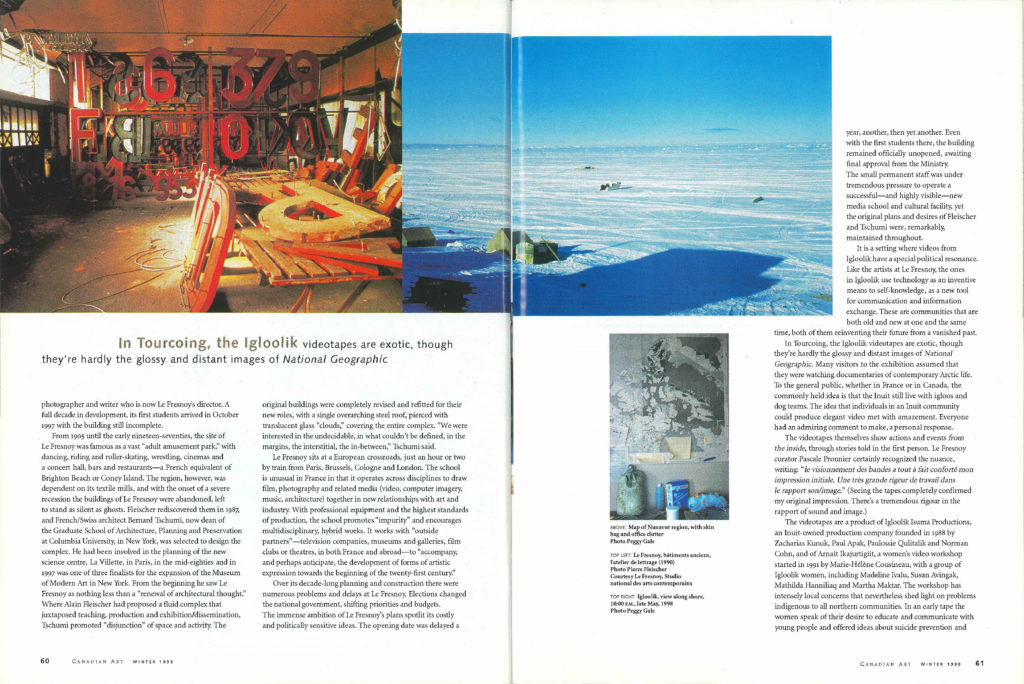

Le Fresnoy, too, is both new and old. It is a post-graduate school for advanced artistic and audio-visual work, with an international roster of teachers and visiting artists. They take on just twenty-four students for each year of the two-year course. Initiated by the French Ministry of Culture, the project was devised and set up by Alain Fleischer, a filmmaker,photographer and writer who is now Le Fresnoy’s director. A full decade in development, its first students arrived in October 1997 with the building still incomplete.

From 1905 until the early nineteen-seventies, the site of Le Fresnoy was famous as a vast “adult amusement park” with dancing, riding and roller-skating, wrestling, cinemas and a concert hall, bars and restaurants—a French equivalent of Brighton Beach or Coney Island. The region, however, was dependent on its textile mills, and with the onset of a severe recession the buildings of Le Fresnoy were abandoned, left to stand as silent as ghosts. Fleischer rediscovered them in 1987, and French/Swiss architect Bernard Tschumi, now dean of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia University, in New York, was selected to design the complex. He had been involved in the planning of the new science centre, La Villette, in Paris, in the mid-eighties and in 1997 was one of three finalists for the expansion of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. From the beginning he saw Le Fresnoy as nothing less than a “renewal of architectural thought.” Where Alain Fleischer had proposed a fluid complex that juxtaposed teaching, production and exhibition/dissemination, Tschumi promoted “disjunction” of space and activity. The original buildings were completely revised and refitted for their new roles, with a single overarching steel roof, pierced with translucent glass “clouds” covering the entire complex. “We were interested in the undecidable, in what couldn’t be defined, in the margins, the interstitial, the in-between,” Tschumi said.

Le Fresnoy sits at a European crossroads, just an hour or two by train from Paris, Brussels, Cologne and London. The school is unusual in France in that it operates across disciplines to draw film, photography and related media (video, computer imagery, music, architecture) together in new relationships with art and industry. With professional equipment and the highest standards of production, the school promotes “impurity” and encourages multidisciplinary, hybrid works. It works with “outside partners”—television companies, museums and galleries, film clubs or theatres, in both France and abroad—to “accompany, and perhaps anticipate, the development of forms of artistic expression towards the beginning of the twenty-first century.”

Over its decade-long planning and construction there were numerous problems and delays at Le Fresnoy. Elections changed the national government, shifting priorities and budgets. The immense ambition of Le Fresnoy’s plans spotlit its costly and politically sensitive ideas. The opening date was delayed a year, another, then yet another. Even with the first students there, the building remained officially unopened, awaiting final approval from the Ministry. The small permanent staff was under tremendous pressure to operate a successful—and highly visible—new media school and cultural facility, yet the original plans and desires of Fleischer and Tschumi were, remarkably, maintained throughout.

It is a setting where videos from Igloolik have a special political resonance. Like the artists at Le Fresnoy, the ones in Igloolik use technology as an inventive means to self-knowledge, as a new tool for communication and information exchange. These are communities that are both old and new at one and the sametime, both of them reinventing their future from a vanished past.

In Tourcoing, the Igloolik videotapes are exotic, though they’re hardly the glossy and distant images of National Geographic. Many visitors to the exhibition assumed that they were watching documentaries of contemporary Arctic life. To the general public, whether in France or in Canada, the commonly held idea is that the Inuit still live with igloos and dog teams. The idea that individuals in an Inuit community could produce elegant video met with amazement. Everyone had an admiring comment to make, a personal response.

The videotapes themselves show actions and events from the inside, through stories told in the first person. Le Fresnoy curator Pascale Pronnier certainly recognized the nuance, writing: “le visionnement des bandes a tout a fait conforte man impression initiale. Une tres grande rigeur de travail dans le rapport son/image.” (Seeing the tapes completely confirmed my original impression. There’s a tremendous rigour in the rapport of sound and image.)

The videotapes are a product of Igloolik Isuma Productions, an Inuit-owned production company founded in 1988 by Zacharias Kunuk, Paul Apak, Paulossie Qulitalik and Norman Cohn, and of Arnait Ikajurtigiit, a women’s video workshop started in 1991 by Marie-Hélène Cousineau, with a group of Igloolik women, including Madeline Ivalu, Susan Avingak, Mathilda Hanniliaq and Martha Maktar. The workshop has intensely local concerns that nevertheless shed light on problems indigenous to all northern communities. In an early tape the women speak of their desire to educate and communicate with young people and offered ideas about suicide prevention and ways to preserve the culture. They went on to record ten hours of interviews with elders in the community and as many hours with midwives of the old days: important archives that already would be difficult to assemble. In 1992 they produced the fine twelve-minute Qulliq, in which women prepared and lighted a traditional stone seal-oil lamp—a woman’s responsibility and the sole source of heat and light in the old days.

But Igloolik Isuma Productions is the more visible presence in the exhibition. Co-founders Kunuk and Cohn had met in 1985 at a video training session in Iqaluit; Kunuk was a professional artist and already working at the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation but “wanted to learn more about what you could do with a camera.” Cohn was leading the seminar, having produced dozens of independent videoworks since 1970 and having had a solo exhibition the previous year at the Art Gallery of Ontario, which toured much of Canada. It was evident to both that they should work together, and, a couple of years later, the Montreal-based Cohn moved permanently to Igloolik.

The works of lsuma recreate Inuit stories and realities of the recent past. Qaggiq (Gathering Place), of 1989, and Nunaqpa (Going Inland), of 1991, were the collective’s first joint works. These stories were set in the nineteen-thirties and nineteen-forties, that is, after the white whalers and priests had arrived, bringing rifles and metal tools, tea and tobacco—but before families had given up their life on the land for settlement in permanent villages. In these tapes we see the old life, as if it still existed, when everyone wore skin clothing, travelled by dog team, lived in igloos and skin tents, ate only what could be killed by the men or gathered by the women and children.

Nunaqpa is a drama conceived by Kunuk in collaboration with his actors, but it is no fiction and there is little “story.” The viewer feels simply transported to the place and time depicted; invisible, comfortable, one is “just there” as folks go about their lives. Somehow, following the families on this caribou hunt—walking, shooting and skinning the animals, cacheing the meat—seems perfectly natural, as if there’s nothing odd or difficult about recording and “packaging” this experience of the past/present. The seamlessness of the work and the easy comfort of the actors lead the viewer to forget this is a construction, prepared for the camera and for an eventual audience.

But this is not really a documentary, for the Inuit no longer live on the land in small family groups. In the past forty years the Inuit have largely been brought into newly established communities; they live in prefabricated houses and drive snowmobiles, wear clothing of wool and synthetic fibres, do their shopping at the Northern stores or the Co-op. Nunaqpa, like Qaggiq before it, shows a past that now exists only in memory…but it is a memory still alive for the elders of these communities. There are still individuals who know how to design and construct a kayak, make a traditional harpoon or fashion clothes from seal and caribou skin.

Seated around a kitchen table in Igloolik last May, I listened to the conversation of two women who have been actors with Isuma. Madeline Ivalu confided that wearing the caribou amauti against her bare skin made her think of her parents and how they lived; she was glad to have had the experience of that now. Micheline Ammaq agreed about the pleasure in that knowledge, but laughed that she likes living today, when it’s so much easier just to toss clothes into the washing machine when they get dirty.

The early works led to the Nunavut series, thirteen half-hour programs for television that trace traditional life through the seasons. Completed in 1995, they have been broadcast regularly on Television Northern Canada and on stations in several provinces, and have been screened (and won prizes) at numerous international festivals. Producing these works is no easy matter, given the realities of light and weather-months with no daylight, when brutal temperatures often make video recording impossible. Long dusks and white sky erase shadows and flatten images. Even more basic, how to record family action in the cramped quarters of an igloo? What to do with fractious children? And when the set must look isolated in an infinite and unpopulated landscape, what to do with all the paraphernalia of coordination for a film crew? Yet there is little evidence of the rigours of production. As Kunuk says, “We just started. We are in a hurry because our elders are going. Knowledge is going. Pretty soon we’ll all be buried on the hill. It’s a very interesting time for our work. Trying to get things right.” As he points out, “You can just talk about the old days, but you can also show the old days. Actually seeing it, you get more pleasure out of it.”

Since 1995 Isuma has been working towards a feature-length film that recounts the story of Atanarjuat, the fast runner. A lot of new research was needed since the film was set in an Igloolik 500 years earlier, before Europeans arrived with wood and metal. Sleds had to be constructed from whalebone and tools made of stone and bone. Different styles of clothing were called for, and tattoos for the women. Planning was taken to a whole new level, for the improvised dialogue and general agreement on storylines suitable to earlier projects couldn’t be used this time. Two fully developed scripts were crafted. The original idea and the complete Inuktitut version came from Paul Apak (to be used by the actors) while the English version was created by Cohn and Anne Frank, going through dozens of rewrites to ensure funding by Telefilm.

No one denied the political implications of this project. As Cohn points out, “It’s a backing-up of the cultural argument that brought Nunavut into being, the argument that negotiated the land claim, the argument that produced community empowerment-that Inuit want to be in charge of their own future, of their own representation, of how they are filmed.” The budget was to be $2 million, “a film by Inuit and for Inuit” that would be Canada’s first feature-length movie produced, written, directed and acted by Inuit or, for that matter, by any aboriginal group. They raised a half-million dollars for the project from some seventeen sources, including Global TV, CBC and Telefilm.

In May 1998, however, the production was closed down after four weeks of shooting, when the Canada Television, Cable Production Funds said they “did not anticipate” Atanarjuat would require their funding this year. In the flurry of angry press releases and interviews that followed, Isuma accused the funding agency of treating the Inuit application “as if we didn’t exist.” As Kunuk insists, “This is an exciting action thriller, not a welfare grant. Atanarjuat is a universal story with emotions people all over the world can understand. Here in Igloolik we’ve motivated young people to respect their culture and elders to help preserve it for future generations. Other Canadians deserve the right to see for themselves.”

Zacharias Kunuk, director/cameraman/editor with Isuma, was born out on the land, into the ancient tradition of igloos and sod winter houses, skin tents in the summer, a nomadic life. He lived there with his family until 1966, when he was nine, then he was forced to attend school, boarding with a local family in nearby Igloolik. He says, simply, “It was awful.” Kunuk is one of the bridge generation, effective in both worlds.

The old way of life is gone now. People live in well-built and well-serviced houses in permanent communities. Water, electricity and fuel are delivered and refuse is collected. Things are expensive—one and a half to two times more than in Montreal for example—but there are stores with food, clothing, tools and furnishings, there is TV and radio, news and information, skidoos and trucks, hospitals with medivac services, airplanes. People pay taxes. There are computers, fax machines, the Internet. All of these changes have arrived in just forty years.

There are other developments. Inuit now have seven times the national rate of suicide. There are problems with alcohol and drugs, dependence on social assistance. There is no doubt that the tremendous social upheaval has been stunning.

But similar problems seem more hopeless, for example, in small Newfoundland communities, where traditional ways of life have also been destroyed and young people have little local pride or ingenuity. Rural areas in Quebec and much of Canada all have versions of these problems, fuelled by pessimism and inertia, an uncertain future, and the relentless pressure of urbanism, capitalism and homogeneity.

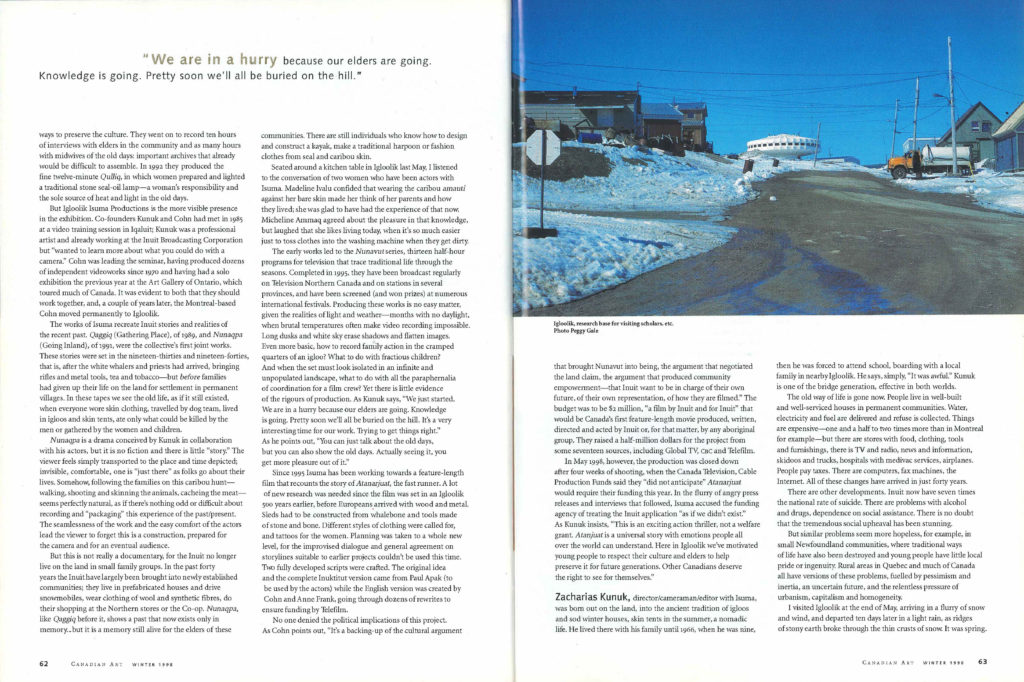

I visited Igloolik at the end of May, arriving in a flurry of snow and wind, and departed ten days later in a light rain, as ridges of stony earth broke through the thin crusts of snow. It was spring. The flowers would appear soon, though the sea ice wouldn’t really melt for another month or more.

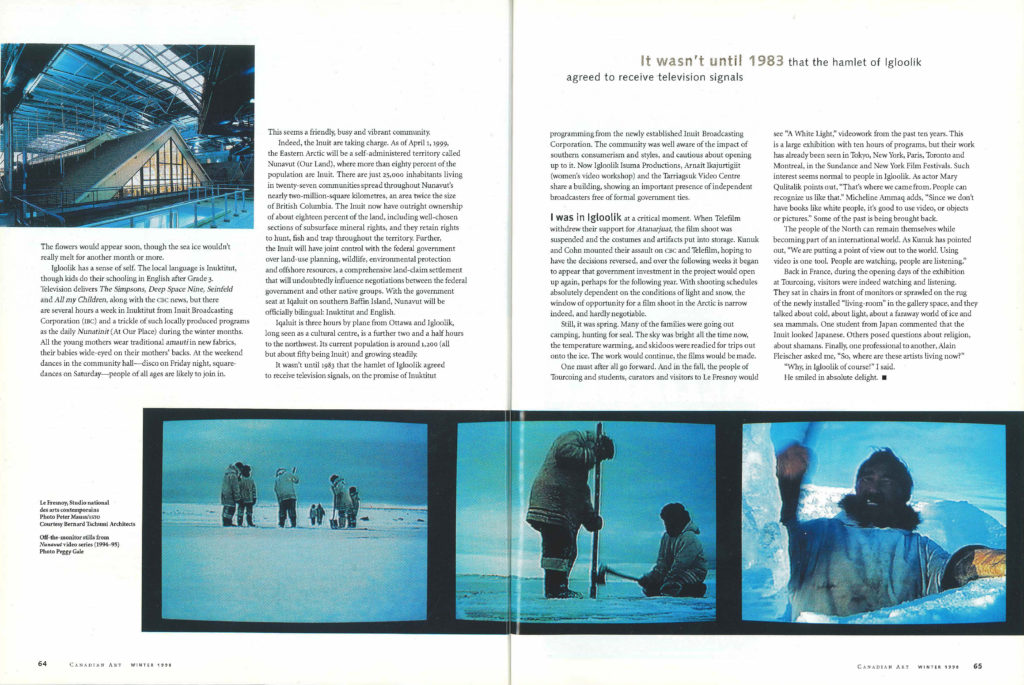

lgloolik has a sense of self. The local language is Inuktitut, though kids do their schooling in English after Grade 3. Television delivers The Simpsons, Deep Space Nine, Seinfeld and All my Children, along with the CBC news, but there are several hours a week in lnuktitut from Inuit Broadcasting Corporation (IBC) and a trickle of such locally produced programs as the daily Nunatinit (At Our Place) during the winter months. All the young mothers wear traditional amauti in new fabrics, their babies wide-eyed on their mothers’ backs. At the weekend dances in the community hall-disco on Friday night, squaredances on Saturday-people of all ages are likely to join in. This seems a friendly, busy and vibrant community.

Indeed, the Inuit are taking charge. As of April 1, 1999, the Eastern Arctic will be a self-administered territory called Nunavut (Our Land), where more than eighty percent of the population are Inuit. There are just 25,000 inhabitants living in twenty-seven communities spread throughout Nunavut’s nearly two-million-square kilometres, an area twice the size of British Columbia. The Inuit now have outright ownership of about eighteen percent of the land, including well-chosen sections of subsurface mineral rights, and they retain rights to hunt, fish and trap throughout the territory. Further, the Inuit will have joint control with the federal government over land-use planning, wildlife, environmental protection and offshore resources, a comprehensive land-claim settlement that will undoubtedly influence negotiations between the federal government and other native groups. With the government seat at Iqaluit on southern Baffin Island, Nunavut will be officially bilingual: Inuktitut and English.

Iqaluit is three hours by plane from Ottawa and Igloolik, long seen as a cultural centre, is a further two and a half hours to the northwest. Its current population is around 1,200 (all but about fifty being Inuit) and growing steadily. It wasn’t until 1983 that the hamlet of lgloolik agreed to receive television signals, on the promise of lnuktitut programming from the newly established Inuit Broadcasting Corporation. The community was well aware of the impact of southern consumerism and styles, and cautious about opening up to it. Now Igloolik Isuma Productions, Arnait Ikajurtigiit (women’s video workshop) and the Tarriagsuk Video Centre share a building, showing an important presence of independent broadcasters free of formal government ties.

I was in Igloolik at a critical moment. When Telefilm withdrew their support for Atanarjuat, the film shoot was suspended and the costumes and artifacts put into storage. Kunuk and Cohn mounted their assault on CBC and Telefilm, hoping to have the decisions reversed, and over the following weeks it began to appear that government investment in the project would open up again, perhaps for the following year. With shooting schedules absolutely dependent on the conditions of light and snow, the window of opportunity for a film shoot in the Arctic is narrow indeed, and hardly negotiable.

Still, it was spring. Many of the families were going out camping, hunting for seal. The sky was bright all the time now, the temperature warming, and skidoos were readied for trips out onto the ice. The work would continue, the films would be made.

One must after all go forward. And in the fall, the people of Tourcoing and students, curators and visitors to Le Fresnoy would see “A White Light,” videowork from the past ten years. This is a large exhibition with ten hours of programs, but their work has already been seen in Tokyo, New York, Paris, Toronto and Montreal, in the Sundance and New York Film Festivals. Such interest seems normal to people in Igloolik. As actor Mary Qulitalik points out, “That’s where we came from. People can recognize us like that.” Micheline Ammaq adds, “Since we don’t have books like white people, it’s good to use video, or objects or pictures.” Some of the past is being brought back.

The people of the North can remain themselves while becoming part of an international world. As Kunuk has pointed out, “We are putting a point of view out to the world. Using video is one tool. People are watching, people are listening.”

Back in France, during the opening days of the exhibition at Tourcoing, visitors were indeed watching and listening. They sat in chairs in front of monitors or sprawled on the rug of the newly installed “living-room” in the gallery space, and they talked about cold, about light, about a faraway world of ice and sea mammals. One student from Japan commented that the Inuit looked Japanese. Others posed questions about religion, about shamans. Finally, one professional to another, Alain Fleischer asked me, “So, where are these artists living now?”

“Why, in Igloolik of course!” I said.

He smiled in absolute delight.

This article appeared in the Winter 1998 issue of Canadian Art.