In the gridded black-and-white photo series Alex & Rodger, Rodger & Alex, a man in a bandana sits against a rock while light hops across his body across each picture, reflected from a pocket mirror held by another man with his back to the camera. The square of light jumps from limb to limb and, somewhere between each image, the time and space between their bodies folds, danced away by a piece of sun.

In 1981, Vincent Trasov and Michael Morris, tired of the bureaucrats they had become during their time at Western Front, came to a porous, Cold War–divided West Berlin.

These images were taken by Canadian artist Michael Morris on the West Coast of Canada in 1970. Captured during the nascent days of the artist collective Image Bank’s collaboration, the light that transcends distances between friends in Alex & Rodger, Rodger & Alex seems to mark a foundational idea for the group, which was founded by Morris, Gary Lee-Nova and Vincent Trasov in British Columbia that same year. What the three subsequently created evades easy categorization, ranging from political campaigns to mail art to brick-and-mortar network-building, all made with a wide weave of like-minded artists.

The serene assemblage of Alex & Rodger, Rodger & Alex was the establishing image in a retrospective on Image Bank at Berlin’s KW Institute for Contemporary Art this summer. The eponymous show, co-organized by Scott Watson, director and curator of the Morris and Helen Belkin Gallery in Vancouver, will get an expanded run in 2020 at the BC institution. While Germany may at first seem like an unusual first stop for a show that is crucially centred on West Coast Canadian art (Image Bank’s archive, now re-christened the Morris/Trasov Archive, is permanently housed at the Belkin), there is a critical, decades-old Vancouver-Berlin bond, deeply connected to these two artists and woefully overlooked in the Berlin chapter of the show.

Image Bank’s certain role in developing a pan-Canadian art discourse is well understood (and, thanks to them, expertly catalogued). Their cohort ushered in an imperative for imaginative reorganization, each artist marked by a desire to create open-source methods for creative communication through a very tactile approach to early 1970s thinking. At the time, documents like the Whole Earth Catalog were being published in the US, while endeavours like Fluxus were manifested abroad. N.E. Thing Co. and General Idea, along with its affiliate magazine FILE, were being founded in Canada.

Alan Kaprow, Joanne Danzker, Michael Morris, Steve McCafftery and Robert Filliou in front of The Western Front in 1974.

Alan Kaprow, Joanne Danzker, Michael Morris, Steve McCafftery and Robert Filliou in front of The Western Front in 1974.

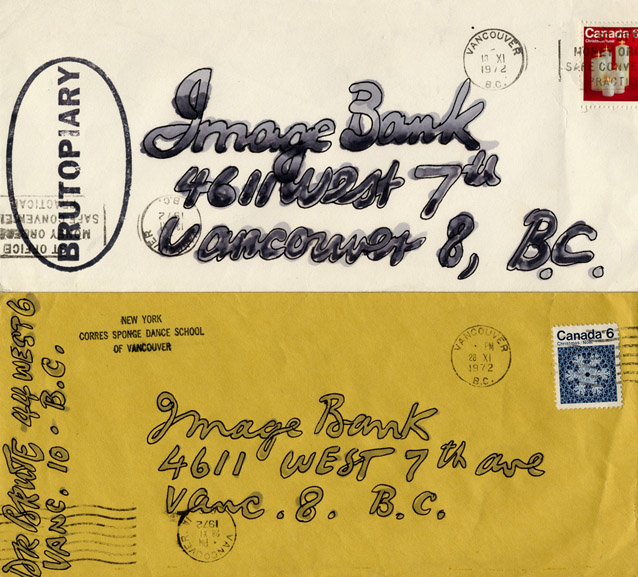

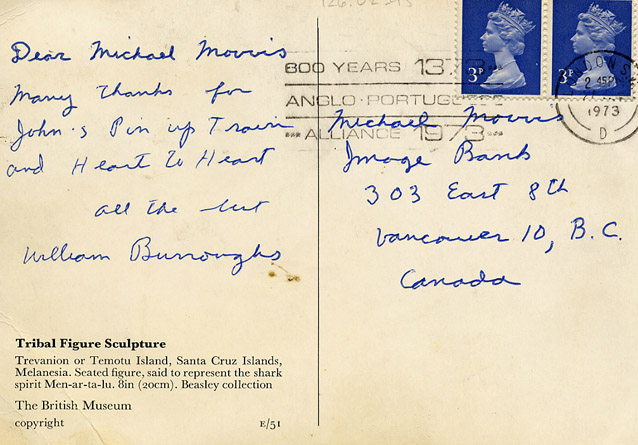

For their part, Image Bank established a network of mail-out requests, where they solicited artists to send them images based on broad themes (subjects included “piss pics” or “beauty pageants”). The mailed material was addressed to Morris, Trasov and others in the network (one mail-out request asked that “generalities” be sent to General Idea’s Toronto address). Through a coordinated cacophony of expression, Image Bank built a network where creative data was dispatched between a diverse group that, beyond the core founders, included contributors like William S. Burroughs, Ray Johnson, Joseph Beuys and Robert Filliou.

The KW Institute for Contemporary Art charts the network’s activity well and the Belkin probably will too. What’s often glazed over in the celebration of these artists are the points and periods when their creative life does not exactly fit into the rubric of Canadian self-understanding, nor into the criteria for Image Bank production directly. In 1981, Trasov and Morris, tired of the bureaucrats they had become during their time at Western Front, came to a porous, Cold War–divided West Berlin. It was a city similar to Vancouver in that it was defined by its existence as a periphery of the Western world. Shedding the Image Bank name, Morris and Trasov attended the DAAD Berlin Artists-in-Residence Programme, one of Germany’s—and the world’s—most renowned international artist portals, and then went on to spend more than a decade in the city. DAAD continues to spark a succession of Canadian artists’ arrival here, including General Idea’s AA Bronson, Liz Magor and Judy Radul. At this point, the cross-pollination between Canadian and German artists is so much to record that it also deserves its own archive, but many can agree that Morris and Trasov predated most of it by years, finding an uncharted kind of creative freedom in Berlin, and instituting a groundwork connection that lives on today.

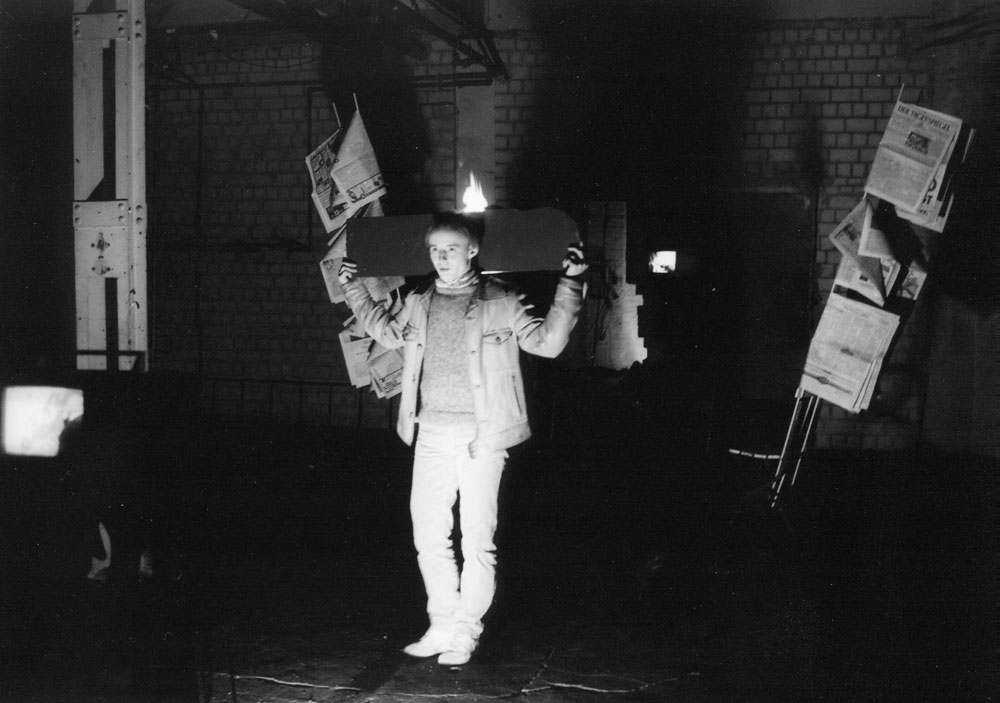

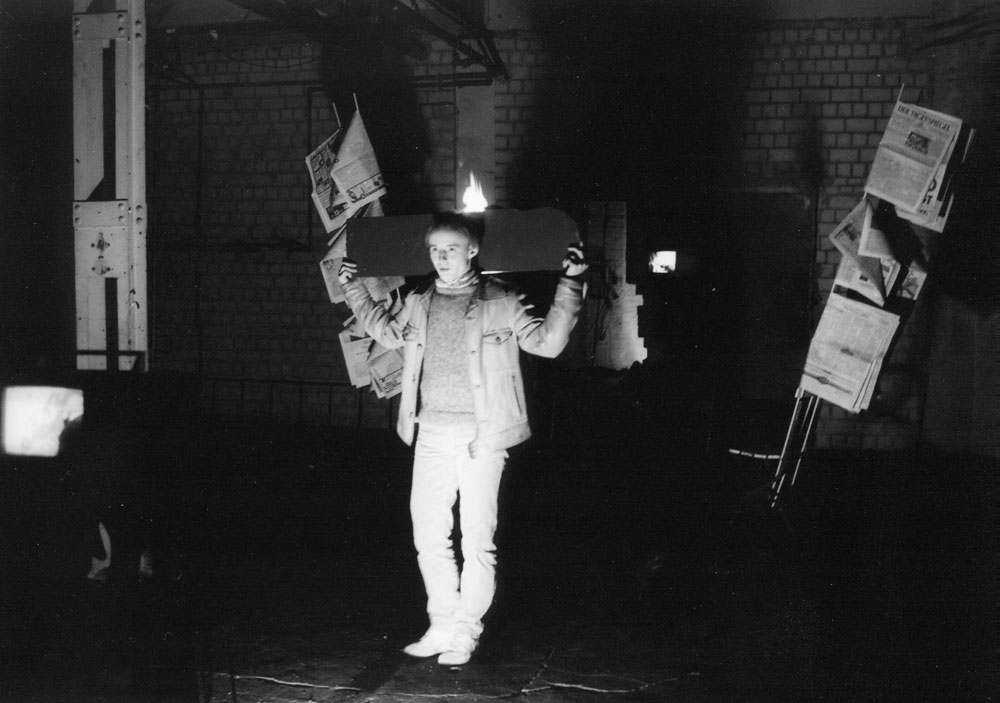

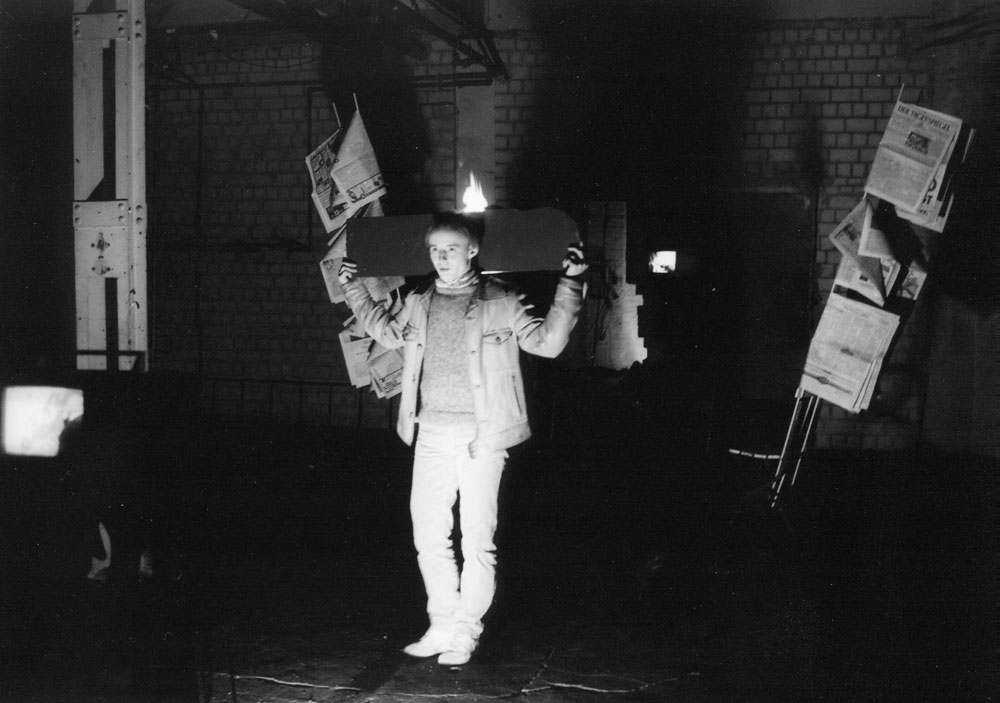

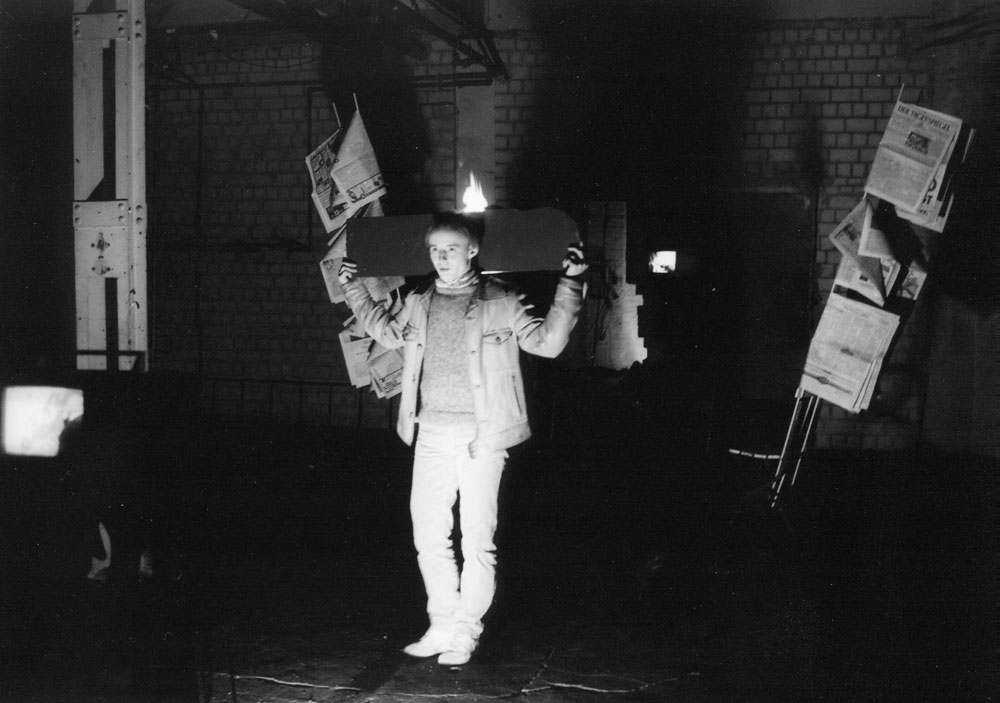

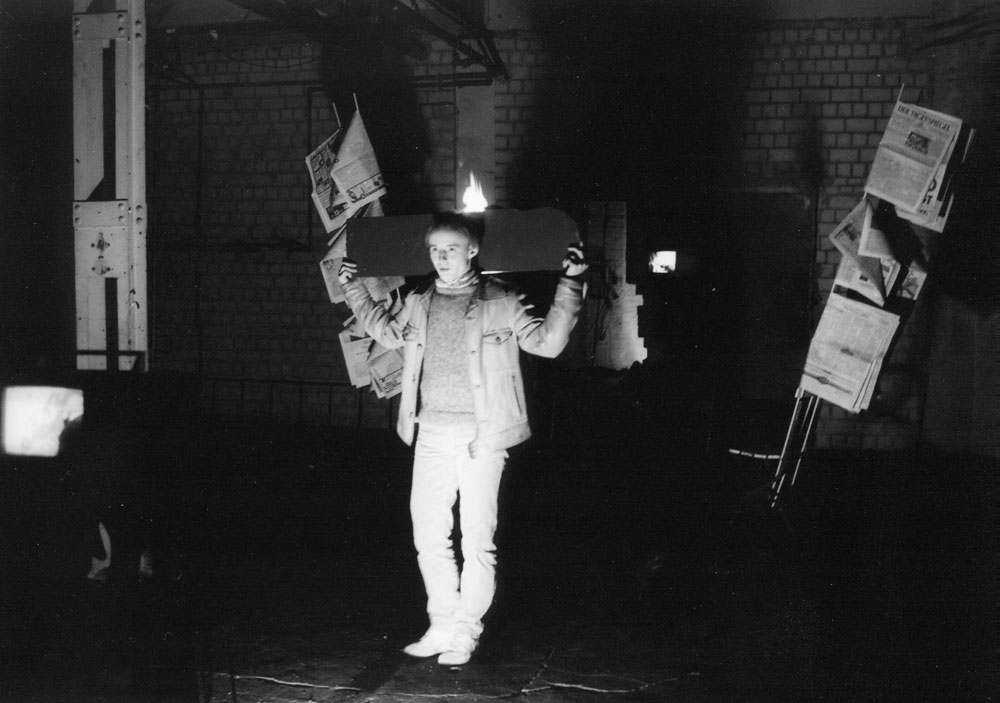

Vincent Trasov, Hell and the Weatherman, (performance documentation, Berlin, 1984. Courtesy Vincent Trasov.

Bill Gaglione, Dadaland Vile envelopes, San Francisco, 1976. Envelope, 10.7 x 24 cm. Courtesy Vincent Trasov. Photo: Morris/Trasov Archive.

Vincent Trasov in Berlin. Courtesy Vincent Trasov.

File Megazine, 1984. Issue Vol. 4 No. 1, Summer 1978. Courtesy Vincent Trasov. Photo: Morris/Trasov Archive.

1984 contribution to Image Bank request mailing, 1972. Courtesy Vincent Trasov. Photo: Morris/Trasov Archive.

Piss pic contribution to Image Bank request mailing, 1972. Courtesy Vincent Trasov. Photo: Morris/Trasov Archive.

Eric Metcalfe (Dr. Brute) mailing page, c. 1971-1973. Courtesy Vincent Trasov. Photo: Morris/Trasov Archive.

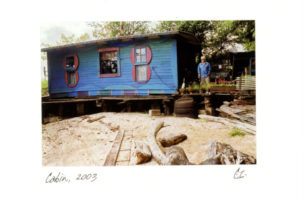

After seeing the exhibition, I experience how the communication nodes that link the lavish West Coast and the concrete grids of Berlin seem to endure in some of its structure. Via a network of friendships that span the Atlantic, I end up, rather serendipitously, on the phone with Michael Morris and Vincent Trasov while they sit together on Vancouver Island and while I sit in Berlin. For years, the two have made a habit of spending summers on the West Coast, though Morris lives there full-time and Trasov is still living in Germany throughout the year. They recall how, in the 1980s, they would leave behind their Berlin apartment and head to the Sunshine Coast for summers at Babyland, a residency they developed on a strip of land outside Vancouver, not so far from where there are now. Trasov is going there soon. They reminisce about how friends (and friends of friends) would rent their Berlin apartment while they were away. Incidentally, Morris and Trasov transplanted Canadians to West Berlin, which was then encircled by the Berlin Wall. Today, in a very different landscape, I feel I am in that lineage, a part of their web of relations.

Are our experiences paralleled? Perhaps not. After my own years living in Vancouver, friends (and friends of friends) stirred up in me an unignorable impetus to move here, to the German capital, in search of some kind of undefinable freedom in the early 2010s, spurred by being priced out of my shared house in East Vancouver, a typical coastal home ripe for demolition, rezoning and condos. My search could reflect the dreamy quality of their early 1980s mentality, except that mine was defined by real estate, not purely by hunger for creative space. Ironically, Berlin now has similarly become an increasingly expensive city to live in.

In the 1980s, the dynamic cultural sphere of West Berlin was becoming, not dissimilar to Vancouver, but born of course from incomparable situations, a place absolutely teeming with creativity.

“Vancouver wasn’t a part of the marketplace in Canada and, at that time in Germany, the art market centres were Cologne and Frankfurt,” Morris says. “Because of this, both Vancouver and Berlin were similarly put together by artists’ concerns and interests.” Morris and Trasov relocated some years after establishing their art practice, after co-founding Western Front—what is now an internationally recognized institution and one of the first Canadian artist-run centres—and after launching their epic artists’ directory in 1974 with General Idea’s FILE. They tell me how they left Image Bank tucked away in boxes in the basement of Western Front, located on 8th Avenue East, to get on an international flight. In Berlin, they built out their network in a different way, as individual artists. The two continued to find a natural extension of the communications project that was inherent in so much of the work they made beyond the more fabled Image Bank years. It was critical for their practices to do this, and the grey city blocks of West Berlin provided flexibility that the shadows of the mountains (which divided them from the rest of Canada) couldn’t. That epoch of the German capital, the time of the New Wild Ones (West Berlin artists, shadowed by the wall and banging up against it), has become the stuff of cultural legend.

So there they were–and the Berlin they would have arrived to is the one my expat generation is still chasing through a hellbent nostalgia, whether or not it actually existed as we have imagined it. In the 1980s, the dynamic cultural sphere of West Berlin was becoming, not dissimilar to Vancouver, but born of course from incomparable situations, a place absolutely teeming with creativity, and still reeling from David Bowie’s Berlin period, which had just reached its poetic climax. His relentless pop song “Heroes” reverberates in each story from the time, Bowie’s words emotionally juxtaposing the radical separation inflicted by the wall: “Though nothing, nothing will keep us together / We can beat them, forever and ever.” Sprays of wrenching guitar and dark West Berlin apartments: “Though nothing will drive them away / We can be heroes, just for one day / We can be us, just for one day.” The song oscillates between the oxymoronic possibility of togetherness in a surreal, cut-off environment.

I’m hesitant to ask them about Bowie, but Morris brings him up anyway without prompt. He recalls Dschungel, a legendary West Berlin nightclub: “Bowie introduced fashion into the art scene in Berlin, the same way that General Idea and AA Bronson brought glamour to Canadian art.” Morris recalls how Bowie encouraged punk singer Salomé to go to art school, and how he then went on to become one of Germany’s most famous painters from the era. Bowie was an outsider stirring everything up, driving around Berlin like a maniac, exercising freedom and injecting perspective.

William S. Burroughs postcard to Image Bank, 1973. Courtesy Vincent Trasov. Photo: Morris / Trasov Archive.

William S. Burroughs postcard to Image Bank, 1973. Courtesy Vincent Trasov. Photo: Morris / Trasov Archive.

Little connects Vancouver’s psychic space with that of Berlin beyond a yearning to carve out total freedom. Vanguards often begin on peripheries, unwatched, more free. Specifically looking at the Image Bank generation in Vancouver and the New Wild Ones in West Berlin, it seems to me that remoteness, affordability, resources (space) and a feeling of disconnection are crucially shared, and so it makes sense to make work so uninhibitedly subjective. Critic Nancy Shaw writes about the situation that bred this distinct generation of Vancouver-based artists, which included Morris, Trasov and Lee-Nova. It was “a generation subjected to the Cold War, the war in Vietnam, consumerism and the conservative morality of the 1950s,” writes Shaw. “They were, in effect, enacting a countercultural rebellion to blur the boundaries between art and life.” It was a group that defined itself by what it was not. The New Wild Ones, which, in one way, were part of a greater political project, were similarly aware of an opponent, though it was geographical, not generational.

Trasov, Morris and I ruminate about the similar trajectories of Vancouver and Berlin, the way two fringe cities became real-estate hotbeds, increasingly unliveable for artists. “It’s very nice that artists are coming to live in Berlin, but it’s after the fact now,” Trasov points out, and I tend to agree. At KW, where the Image Bank show went on view and wrapped up in a distinct end-of-summer mood, is a reputable centre for art exhibitions, located in a gentrified neighbourhood. But it began as a project space some years after the wall fell, and was like Western Front, but in this case in the eastern part of the city in the far east of Germany. Today, rent anywhere nearby KW is hardly affordable and it’s no exception across town. “Berlin, like Vancouver, has become quite a conservative centre. Artists are being forced out by an exorbitant cost of living.” Trasov tells me he donated some works to the first auction KW held, in the early 1990s. “The neighborhood around KW was a ruin,” Trasov remembers. “The time of its founding was similar to Western Front, in that it was trying to get an unknown thing born.”

I ask Morris about the men in the Alex & Rodger, Rodger & Alex photo series. He tells me they were all friends—one he knew from art school; the other was visiting from Toronto. They’re not alive anymore. The period of the 1980s was marked by political gridlock, but also by the AIDS epidemic. “We were meeting people from all over the world who we thought we were going to collaborate with for the rest of our lives,” Morris recalls. “By the 1980s, a lot of our friends from New York ended up coming to Germany to die. There was the glamour of Bowie, but there was a dark period that began almost immediately when we got there.” Morris turned to making more figurative work, painting the friends of his who were dying. Work, he says, he has never exhibited.

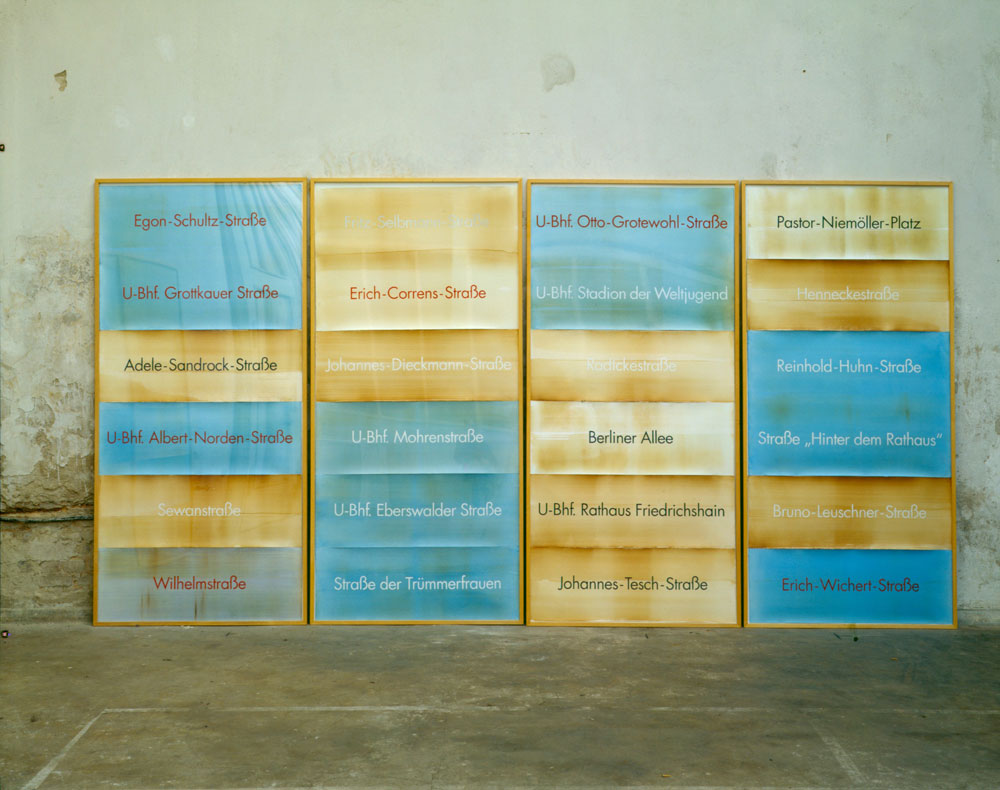

Vincent Trasov, Strassenbild (detail), 1991. Courtesy Vincent Trasov.

Vincent Trasov, Strassenbild (detail), 1991. Courtesy Vincent Trasov.

Trasov tells me about a large painting he created from 1990, after the fall of the wall, called Strassenbild (translated to Streets Painting), which replicates street names from old East Berlin honouring communist revolutionaries, which were rapidly replaced after the wall came down. He included the substitute streets they suddenly became when a problematic history was problematically erased. Perhaps helped by his subjective distance as a foreigner, Trasov distilled the colonization of the Eastern Bloc that ripped through Berlin like a wildfire. Today, Germany is still trying to come to grips with that reunification history and to find a language for it, but it’s here, so very early on, in an austere painting by an ausländer—an outlander. Looking at the work, it’s hard to know which names were obsolesced and which ones were new, but what at the fore is the lingering, poetic illogic of Morris and Trasov’s Image Bank-inflected lineage of disruptive thinking. Strassenbild is now in the collection of the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin.

The Canadian government has, appropriately I think, begun to acknowledge the critical role outlier cities and nations play in the continuous evolution of Canadian art discourses. Next year, Canada will be the guest of honour at the Frankfurt Art Book Fair, and the Canada Council is rushing to furnish short-term projects abroad. But what about the long view? While it’s encouraging to see the nation better understand that its very nationhood is a problematic myth, I would hope that Berlin and other places like it are more consistently considered part of that mythos.

Their legacy lies well within but also outside the mapping of that summer show at KW; it is relatable to the hyper-networked yet isolated worlds we live in today. It speaks volumes to a travel-riddled, social media-steeped art scene set against a fracturing social reality at large. It lies in a fibrous connectivity bred by questioning systems of self-organization. The Morris/Trasov Archive and its associated work consists of many moving parts, but there is an expatriation of the self from the self, through costume, alias and a desire for collectivist anonymity. Not to mention physical disruption—that is, disruption as departure from known quantities—like home. While cities like Berlin and Vancouver grow increasingly unaffordable for the kind of productivity artists like Morris and Trasov were able to pioneer, we will certainly need to continue to use critical distance as an unruly ethos, just as they did. “Communism ended in a weekend. It affected so much of the 20th century and it was this gigantic edifice, the wall an icon of it,” Morris says, shortly before we end our call. “Systems can collapse instantly, as Vincent and I witnessed. That is a lesson that we need to consider within the world we are in now. We can destroy things that stood for a long time, very quickly.”

For now, we have Alex and Rodger and the light shared between them.