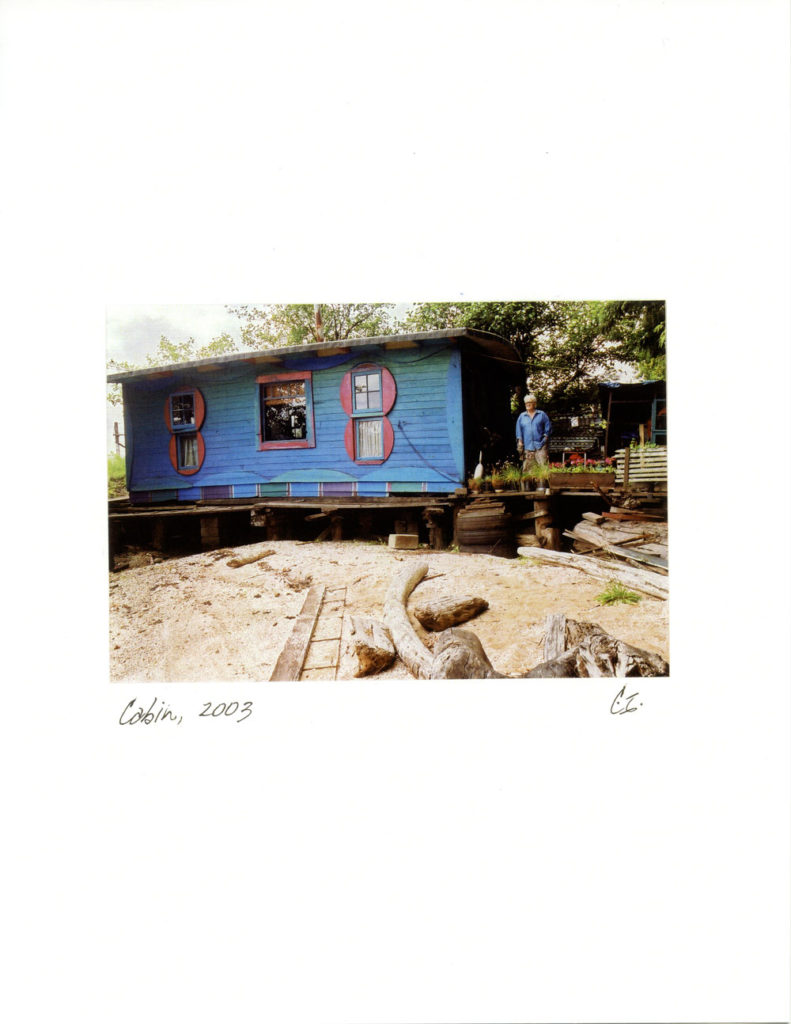

Not much happens along Old Dollarton Road in North Vancouver during the wee hours of the morning. The Tim Hortons closes at 9 p.m.; the Narrows Pub across the parking lot only stays open a few hours later than that. But last year, in the still, early hours of June 6, the Supreme Movers crew were on the road with a little blue cabin strapped atop their huge red truck. The structure bore little resemblance to their usual cargo—the movers are more used to transporting substations, overpasses and bridges. “I think this is the smallest thing we’ve ever moved,” one of the crew members told me with a laugh. The cabin is small by most standards: it’s just 12 feet wide and 24 feet long, with little windows rimmed with scalloped panels painted cherry red and topped by a slightly bowed roof. The truck wound slowly up Old Dollarton Road, and turned into Maplewood Farm, a small heritage farm where children can feed goats and sheep. In a few hours, the sun would rise. The farm would open, and the movers would begin the meticulous, slow process of unloading the cabin from the truck and placing it in a grassy corner of the farm, where it would spend the summer as its new life began.

For some eight decades, the cabin had been sitting just five kilometers to the south on the foreshore next to Cates Park, hidden from the road by towering cedar and fir trees, looking out into the Burrard Inlet. This is not a heritage building with a rigorously documented provenance; how it came to be there remains something of a mystery. There are no definitive historical accounts. The stories, built by research, word of mouth and best-guess estimates, suggest that a Norwegian constructed the cabin in the 1930s. It was originally moored in Coal Harbour—now the terrain of million-dollar, glass-fronted condominiums—but made its way to the Burrard Inlet shortly thereafter. The Norwegian likely moved it so that he could live next door to McKenzie Barge and Derrick Co., a shipbuilding site that opened in 1932. The cabin sat there on its pilings for decades, collecting dust from the sandblasting in the shipyard, mud wasps and powder post beetles from the forest, and new tenants.

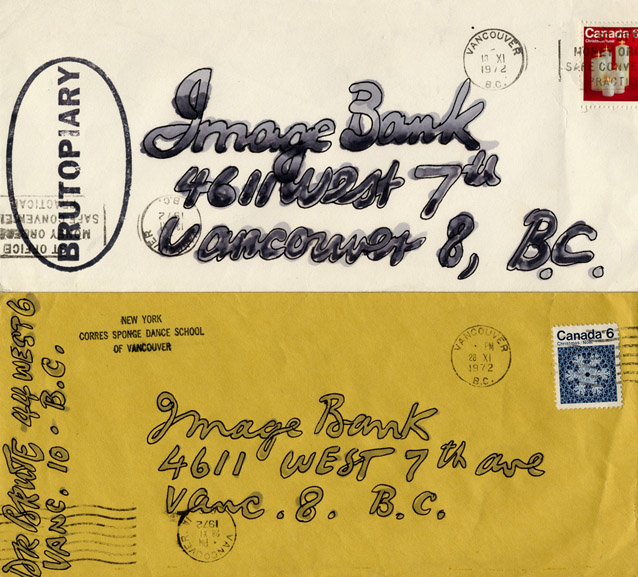

In 1966, Al Neil moved in. He was a musician and an artist who occasionally worked as a sort of watchman for the shipyard. He rented the cabin for $15 dollars a month, and, in the ’70s, he was joined at the cabin by his partner, artist Carole Itter. They lived there part time, spending summer days building large art assemblages, watching the tide going in and out, and having friends drop by for dinner and long conversations into the afternoons. “Both my partner Al Neil and I were quite reclusive, and we went there to have some silence,” says Itter. “It was a hideout, that no one knew about.”

Then, in late 2014, the letters started coming. Port Metro Vancouver wanted Neil and Itter out. The land nearby had been purchased by Polygon Homes, and the developer was planning to build condos. The beach all along the area needed to be remediated after a century of industrial use, and cleaning out the metal and oils meant clearing out the cabin, as well. But who is responsible for a little hidden cabin, with no legal title, sitting on public land?

“I was talking to the people from the port authority asking, what are you doing?” says Glenn Alteen, program director at Vancouver’s Grunt Gallery, and a friend of Neil and Itter’s since the 1980s. “I would say, Al and Carole don’t really own the cabin, it was never their cabin. ‘Well, who does own it?’ they would ask, and I would explain, ‘Nobody really knows.’”

It was the beginnings of a Herculean task for Alteen and a handful of helpers: saving something with no owner, no commercial value and no precedent. Alteen, along with Esther Rausenberg, another long-time friend of Itter and Neil’s and the co-director of C3 Creative Cultural Collaborations, began wading through the bureaucratic nightmare of negotiating with the different parties connected to the cabin—Port Metro Vancouver, the District of North Vancouver and anyone else that could help. Trying to figure out what to do with the cabin became a part-time occupation that has stretched out over the last four years.

Alteen and Rausenberg quickly realized the cabin couldn’t stay on the foreshore, so they began working on a next-best plan: simply save it. They went to the press with the story of the imminent eviction, Itter and Neil moved out their belongings and art, and the little cabin quickly became a rallying cry. Now, four years on, it has been moved, remediated and very nearly transformed into a floating artist residency.

The cabin represented more than an idyllic vacation spot. It marked the end of a way of living. The history of squatting and living in provisional, off-the-grid arrangements has long been entwined with the history of art made in British Columbia, but these romantic models have entered their twilight. Neil and Itter didn’t consider themselves squatters—after all, they had permission from the presumed owners and paid rent for many years—but the cabin is inextricably tied up with the history of squatting on the North Shore. Not far from the blue cabin, in front of Cates Park, Malcolm Lowry lived in a little shack and wrote his famed novel Under the Volcano during the 1950s. A few years later, a ragtag group, including artist Tom Burrows, began building homes and squatting in the Maplewood Mudflats. Their community didn’t last for long—in the late 1960s Mayor Ron Andrews began trying to clear the space for commercial development—but the NFB documentary Mudflats Living left the indelible image of the rickety, makeshift homes up in flames after the 1971 eviction. The slightly utopian, unconventional promise they represented lives on in lore. Not far from the blue cabin’s old home, nestled into the Maplewood Conservation Area, sit three meticulously detailed scale models of the lost Mudflats dwellings by Ken Lum. Perhaps one day, a little version of the blue cabin, with Neil and Itter’s sculptures spilling out and around the building, will join them.

Artists are struggling to afford Vancouver. So is virtually everyone else. Average home prices are more than a million dollars in the Vancouver region, and daily newspaper headlines debate taxation and foreign ownership. These feel like particularly contemporary problems, but land speculation has plagued the region for centuries. “Canada was founded in part by a department store, but Vancouver was founded mostly by real estate developers: the three Greenhorns,” says Lorna Brown, the acting director of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. As Nancy Kirkpatrick, director of the North Vancouver Museum and Archives, says, “Real estate has always been an issue. North Vancouver is built on a hillside and, essentially, it is surrounded on three sides by water. It has always been a more difficult place for a developer to build in because of the nature of the geography.”

Well before any bohemian enclaves of squatters emerged, working-class families were struggling to find housing in the North Vancouver region in the early 1900s. Kirkpatrick and the NVMA team dove into the topic for a 2008 exhibition about tent homes in early North Vancouver, and found many stories of families living in temporary housing. “In 1911, for instance, about one third of the single-family dwelling building permits in North Vancouver were issued for temporary housing. And the local newspaper advertised furnished canvas tents for rent at $2 per month.” And, of course, before there were artists or working families along the North Shore, this was, and is, the terrain of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation. “The idea that British Columbia is mostly unceded is a really important current that is very different from anywhere else in Canada,” says Brown. “It’s unceded land, that has always been acknowledged, so that’s a state of negotiation, of feeling temporary, contingent and provisional.”

Saving the cabin will not puncture Vancouver’s inflated housing bubble, mandate policies for accessible living or spur a large migration to off-the-grid communes. No one involved in the project suffers under any such delusions. This could easily be a story about nostalgia, and perhaps to some degree it is. But it’s more a story about how, sometimes, faced with incomprehensible market forces and a world that seems increasingly chaotic, a group of people can pick one thing—one improbable, inconsequential thing—and save it.

“I think it’s important, with this particular project, to see how many people have come together,” says Rausenberg. “At first, Glenn and I were really in stun mode. We were good at getting the information out, and we got an incredible amount of press—everybody was wanting the story. But we didn’t know what we were going to do with the cabin.” Alteen roped in the help of artist and curator Barbara Cole. She had overseen Cedric Bomford’s installation DEADHEAD, which was mounted on a barge and floated around Vancouver, making her a rare and vital source of knowledge. Cole attended a community meeting in North Vancouver with business people, community and council members in the district, and presented the case for saving the cabin. It resonated. Canexus, a chemical processing plant down by the water, offered their lot as a spot to store the cabin for a couple of years. There was also a helpful twist of fate: Polygon Homes, the developer behind the nearby condominium project, is owned by noted art patron Michael Audain. With his financing, the team built a road down to reach the little cabin. Supreme Movers carefully hiked it up onto a truck and carted it over to the chemical plant where it would sit for almost two years, waiting for a plan to emerge. As Michael Jackson, a project manager who volunteered to organize much of the project, told me last summer, “You could build a replica for a fraction of the cost.” He paused. “But that’s not the point.”

They had saved the cabin. Now they just needed to figure out what to do with it. “Everything about this project is really, really complicated,” says Alteen. Imagine you had saved a storied cabin and wanted to turn it into a residency on water. Where would you start?

Every inch of the cabin was carefully looked over and restored, but at what point have you replaced or repaired so much of something that it becomes something new?

There were more logistics to navigate, funds to raise and a time-consuming conservation project. The empty cabin was moved last June from the Canexus lot to the nearby Maplewood Farms, a property of the District of North Vancouver, which offered a more accessible temporary home for the remediation process. Artists Jeremy and Sus Borsos began working on the cabin in June, and continued almost every day until mid-October of 2017. They removed timbers, surveyed floors, sanded boards, installed joists, worked on vapour barriers. “There are a lot of difficult decisions to make because you want to preserve it as it is, but you can’t preserve it as it is,” says Sus Borsos. Multiple lifetime’s worth of objects and ephemera were pulled out from underneath floorboards and behind the wall spaces of the cabin. (Some things, though, were never found—writer Michael Turner remembered losing a centennial nickel with a rabbit on it in the cabin years ago, but the coin didn’t turn up in the Borsos’s excavation.) Among the most impressive of finds was a cache of early-20th century posters, which advertised all kinds of events, like boxing fights and shows featuring John Philip Sousa and his band playing Vancouver’s Orpheum. Every inch of the cabin was carefully looked over and restored, but at what point have you replaced or repaired so much of something that it becomes something new?

New lives have sprung out of the cabin and its treasures, like fresh saplings out of a fallen nurse log. Jeremy and Sus Borsos created a body of work around the restoration process that showed at Grunt Gallery this summer. Artists Pippa Lattey and Luke Blackstone are now working on a project with the old piano that Neil kept in the cabin. Artist Laurance Playford-Beaudet has researched the remarkable posters that were stashed in the floorboards. And, if all goes according to plan, by the end of the year the cabin, now transformed into a studio, will be placed on a platform. Early next year, it will be combined with new living quarters, and sent out onto the water, possibly moored in False Creek before moving to Indian Arm, offering artists a place to work and live.

Much of the blue cabin’s past lives, though, is lost. Its builder will likely remain a mystery. In November 2017, Neil died at the age of 93. The beach where the cabin was once nestled has been fully remediated. I walked along it last summer and tried to pick out where the cabin would have sat, but the site seems so changed from its former configuration that the closest I could get was closing my eyes and imagining that the smell and sounds and sun could, somehow, take me back.

“Vancouver kills off so much of its history,” says Alteen with a sigh. “It reinvents itself and forgets where it came from, so projects like this are really important to keep that history up in the front so people see it.”

It could be an alternate version of a Georgia Straight headline from earlier this year, “We can’t let Vancouver lose its soul,” or the revised title for a recent CBC piece, “Stay or leave: Vancouver’s artists face dwindling studio space, insecure housing.” It’s a refrain shared by so many generations. The clipping feels a little like a break in time, the chorus of some other era that bears repeating today. It’s a sensibility writ large throughout the mission to save the cabin. Yes, things seem impossible, then as now. And yet, we must resolve to make them otherwise.