Prolific Jamaican-Canadian artist Tau Lewis has been working non-stop and is breaking away from the Canadian art context. She currently has a solo exhibition at Jeffrey Stark in New York and a two-person exhibition with Cheyenne Julien at Chapter NY. Earlier this year she had a solo presentation at Atlanta Contemporary; last fall she participated in a show with the RAGGA NYC collective–of which she is also a member—at MoMA PS1, as well as the group show “TRUE LIES,” at Night Gallery in Los Angeles.

This past weekend, Cooper Cole Gallery, which represents Lewis in Canada, was awarded the Frieze Frame Stand Prize for their outstanding solo presentation of her works at Frieze Art Fair on Randall’s Island in New York. The Focus section of the fair, in which Cooper Cole was invited to participate, allows emerging galleries to present by subsidizing booth costs. Jurors for the prize included curators Elena Filipovic (Kunsthalle Basel) and Jamillah James (Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles). Kapwani Kiwanga, another Canadian artist, won the inaugural Frieze Artist award earlier this year and was supported in her creation of the interactive outdoor installation Shady (2018).

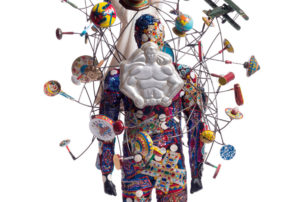

Lewis’s self-taught sculpture practice began just five years ago. Recently, she has been using mostly found materials to make her installations and figurative sculptures. “I am interested in using what’s available to me,” she tells me, and in “building portraits of the landscape that are also telling stories about Black identity.”

Seven of these meticulously sculpted, fantastical portraits are spread across the carpeted floor of Cooper Cole’s square booth, surrounded by a set of walls painted light purple and aquamarine blue. “Walking around the fair it seems like this is the only booth that looks remotely like this,” says Cooper Cole director Simon Cole. “It’s very unique work and people are really engaging with it. Children, adults—everyone kind of has a different reaction to it.”

The following is an interview conducted with the artist over the phone.

Yaniya Lee: Can you talk about the installation, what the booth looked like and how that fits into your practice?

Tau Lewis: There are seven works in the booth and six of them are new. We painted the booth an aquamarine-blue and a sort of purplish-pink based on a house that I had built at 8-11 Gallery in 2017 for a solo exhibition. When I built that house I was trying to mimic the look of the architecture and the landscapes in the Caribbean. We decided to bring those colours back for the fair because they are still relevant to what I’m thinking about now, just a little more than a year later.

The pieces in the booth are all portraits. I think of them as things or beings from an imaginary landscape or an imaginary place. In my work, I think about the undeniable relationship that Black bodies have always had with certain landscapes. I’m also thinking a lot about water systems and deserts and tropics and forests and underground spaces.

I made these portraits to mimic those landscapes in their textures and colours. All of them have frames that are made out of found wire and copper and things that I’ve picked up around my studio, which is in an industrial part of Toronto. They also have things like seashells and stuff sewn into them—I have a box of shells that I started collecting around 15 years ago in Westmoreland, Jamaica. I’m [also] considering the objects that I’m using to build these things, and how those objects have passed through [different] hands and are energetically charged because of that, which helps bring these things to life.

YL: Tell me about the process of creating these works over the past few months. What’s it been like since you found out about this solo presentation?

TL: My practice and the process of creating have always been more about labour than anything else. It’s become more about that in creating these works for Frieze because these particular works are so labour-intensive for me to make. Everything is hand-sewn and the faces and feet are carved out of plaster. I would normally spend up to two months producing one of them, so it’s been really emotional and really intense. Not just the process of creating them but also being with them at the fair [after] being with them in my studio over the last several months and all the time that I’ve spent getting to know and getting to love these things for what they are.

YL: You put so much into your sculptures: there is a life and a soul in each piece. What happens next with the works in the booth? How do you feel about them leaving your life?

They’re not exactly leaving my life. I’ve cried about this since the fair happened and since everything [else] has passed this week. I’ve cried a couple of times about it, not necessarily because of the fact that I have to let them go, but just because I’m feeling the weight of what they are to me and what making them has done for me.

I don’t want to hoard everything; I don’t want to feel like I have to hang on to everything. I am an emotional hoarder and I think it’s a good thing for me and for these artworks to be in the world.

I am lucky that I get to know where they’re going; that they are going to good places. I’m lucky to be able to be transparent with my collectors about how I want these things to exist, and how I want these things to live, because that means everything to me. And I’m just thankful that a few of them are not going very far: a few of them are staying in Toronto and some of them are staying in Canada. I feel excited about the future and getting to see them again after time has passed.

YL: You said you were reflecting on what making them has done for you, what do you mean by that?

TL: I mean that they are a really therapeutic part of my practice: more therapeutic than making an assemblage sculpture and more therapeutic than quiltmaking. Because when we see things that look like us there’s something different that happens. These things really feel like children to me and these repetitive labours that I do in order to make them—such as carving, sewing and even the act of collecting things—is immensely therapeutic for me. It helps me work through life, helps me work through everything.

YL: So what did it feel like to win the prize?

TL: When the prize was announced I was hiding in a park and I didn’t check my phone because I had a feeling that was happening, then [when] I found out I won it I called my mother.

I am fully aware of how hard I’ve worked and how deserving I am. It’s a good feeling, but it’s been a very crazy week for me. I opened another show the day after winning the prize and hadn’t really had a chance to process it yet. But everything feels good and I think it’s much more about the art than it is about me or the gallery and that makes me feel very proud.

YL: What is the range of ways people interacted with the work while you were at the booth?

TL: I was only at the booth two days while the fair was happening. It’s a bit of a hard environment for me to be in. People were really awestruck, especially children. People kept sending me pictures of kids hanging out and just going nuts and reacting to the work. I’m always so much more interested in what children have to say because they don’t have a bullshit filter. Someone sent me a photo of when our booth won the prize and all these people were standing around and in the corner of the photo I could see one of my sculptures looking up at everyone and that’s what makes me feel most proud. If those sculptures were alive all they’d want would be to be noticed by children, and I feel so happy about people noticing these things that have sat in my dank, dark studio for six months.

YL: This recognition of your work is happening in a US context and it’s at a different scale somehow than the reception you’ve had in Canada. Do you feel like people relate to your work differently in the US than they do in Canada?

TL: I do, but that’s only because of the way that I’ve experienced it. New York is the only place in the United States context which I feel like I’m really getting to know. I’m from Toronto which is a lot smaller—our art scene is definitely smaller and sleepier—compared to New York. So there is a different relationship for sure, but it’s mostly to do with volume and scale and taste. There’s just a lot more happening here [in New York]. Hangouts turn into business meetings and it’s like everyone’s on here all of the time.

YL: What are your thoughts on art fairs in general? You mentioned that it’s a hard environment. Are they necessary? Is this your first fair?

TL: I’ve done a few fairs now. I did Spring Break a couple years ago, which is also in New York, and I also did NADA Miami with Cooper Cole. I think that fairs are necessary. Do I think that they show you the scariest parts of the art world? Absolutely. They are a really really difficult place to see your art in, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t still have magical interactions and experiences with artwork.

The demographic of people who will come to an art fair is oftentimes very different from the people who will come to your tiny solo show. It’s the same in terms of buying, so it’s a difficult thing to navigate. But I do think it’s immensely important for a lot of artists for gaining international exposure.

YL: This is an award that will bring you a different kind of visibility. Do you think it will affect the way that you work?

TL: I don’t think it will affect the way that I work. It’s so funny because I had been so tired and starting to feel burdened by how much time I was spending in my studio, but after this week of socializing and all of the commotion, all I want to do is go and be quiet in my studio. I’m so thankful that I have a residency coming up in Kingston [at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre] and it’s going to be quiet and I’m going to work.

I always put a bigger priority on working and researching and experimenting than on exhibiting, so right now I feel really ready to get back to work. Everything else will follow and happen as it should.