In 1911, thousands of individuals in Edmonton generated a petition stating that African and Afro-Indigenous migrants from the southern US states were not welcome in Canada. Later that year, the cabinet of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier drafted Order-in Council P.C. 1911-1324, proposing a ban on Black immigration to Canada. Although the cabinet repealed the order a few months later, its racist sentiment had already increased discrimination and slowed down Black migration. In 1919, Carroll Aikins, a leader in the Little Theatre movement who later became the artistic director of Hart House Theatre at the University of Toronto, wrote the play The God of Gods. It was performed at the theatre in 1922, using “native” motifs and casting white actors in redface to stage theosophist ideas about religion and politics. It was presented as an example of seminal Canadian theatre in the 1926–27 book Canadian Plays from Hart House Theatre, edited by Vincent Massey. It continues to be celebrated as an important play in Canadian history.

To mark the 100th anniversary of Hart House, Barbara Fischer, executive director and chief curator at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, commissioned Deanna Bowen to produce a new body of research. Positioning this play and petition as a nexus, her exhibition branched out to explore the social networks that heavily influenced the formation of Canadian culture in the early 20th century. Bowen visualizes those involved in this formation by examining their books, plays, letters, exhibitions and music, as well as their political appointments and the institutions they founded, including Hart House, the Arts and Letters Club and the Art Gallery of Ontario. Bowen’s work, which includes a feature-length video made with John G. Hampton, Peter Morin, Lisa Myers, Archer Pechawis and cheyanne turions, highlights the nature of this emerging Canadian identity as one shaped by nationalist, white and settler ideals and, more specifically, maps how colonial ideas about Indigenous cultures and cultural production were mobilized to create a national aesthetic that persists to this day. —Maya Wilson-Sanchez

Table of contents for Augustus Bridle’s The Story of the Club (The Arts and Letters Club, Toronto, 1945), from Deanna Bowen’s 2019 exhibition “God of Gods: A Canadian Play.” Collection of Deanna Bowen.

Table of contents for Augustus Bridle’s The Story of the Club (The Arts and Letters Club, Toronto, 1945), from Deanna Bowen’s 2019 exhibition “God of Gods: A Canadian Play.” Collection of Deanna Bowen.

Deanna Bowen: In developing “God of Gods: A Canadian Play,” Maya, the Art Museum’s first Curatorial Residence Award recipient, and I had many discussions about the ways art was, and is, used to generate and disseminate white-nationalist rhetoric to everyday citizens via seen and unseen manoeuvres among Canada’s elite cultural circles. Industrialist and politician Vincent Massey was a central figure in this network, as were Group of Seven painters A.J. Casson, A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, J.E.H. MacDonald and Lawren Harris (who was also a theosophist), alongside a constellation of artists, writers and society figures that included Bertram Brooker; fellow theosophists Albert Smythe, Roy Mitchell and Carroll Aikins; George A. Reid, Sir Byron Edmund Walker, M.O. Hammond, William Southam, Timothy Eaton and University of Toronto German professor Barker Fairley. Our research culminated in an interventionist presentation of archival materials that mapped this social-political network of elite white men. Our experiences in several mainstream archives—including the University of Toronto Archives, the Toronto Reference Library, the Archives of Ontario and Library and Archives Canada—were a starting point to discuss notions of influence: who has it, what it looks like, where it manifests and how it affects the way history is written, overwritten or erased.

The idea of mapping this network of influence evolved out of the absence of archival material about Carroll Aikins’s 1927 to 1929 tenure at Hart House Theatre and my ongoing research into the some 4,300 signatures on the Edmonton anti-Black petition, which I reproduced for my installation 1911 Anti Creek-Negro Petition (2013). The petition reveals an expansive network of white Albertans that included Barker Fairley, who at that time taught at the University of Alberta. Fairley’s signature on the petition is a critical part of this puzzle: he was an ardent advocate for the Group of Seven and their unpeopled landscapes. In the Fall 1948 issue of Canadian Art, he wrote that “we now have a body of landscape painting—Group of Seven and post Group of Seven which warms the hearts of thousands of Canadians and gives them the right sort of national pride.” In both instances, seemingly mundane historical documents (or the lack thereof) speak volumes about the values of a community of like- minded people rallying together to stop the influx of Black Muscogee (Creek) peoples, who were, according to the petition, “deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.” Following Fairley to the University of Toronto, where he taught from 1915 onward, leads to the inner circles of Massey’s Hart House and the Arts and Letters Club. The violent sentiments in the petition, about who constitutes a desirable Canadian, strengthen in time to become a mutually regarded white Imperialist vision among Fairley and his friends.

With this in mind, I couldn’t help but think about the roles institutional archives play in the making and management of a historical narrative. I’m thinking specifically about the ways a personal archive is brought into the institution and the limitations applied to particular material. Our need to gain permission to review Vincent Massey’s archive at the University of Toronto Archives is one example of the kind of intimidating limitation of access that conveys an unspoken message about the importance of the archive and the need to prove our worthiness to review it. This sets up an interesting power play that produces self-doubt and self-censorship—as in, “Who am I to review these documents?”—and a sense that I really needed to be careful in making use of the materials enclosed. One could argue that the formal, performative aspects of the archive retrieval process and the practical aspects of archive management, like donning gloves, etc., are layers of wielded power and meaning-making that inform the valuation of the archival material itself.

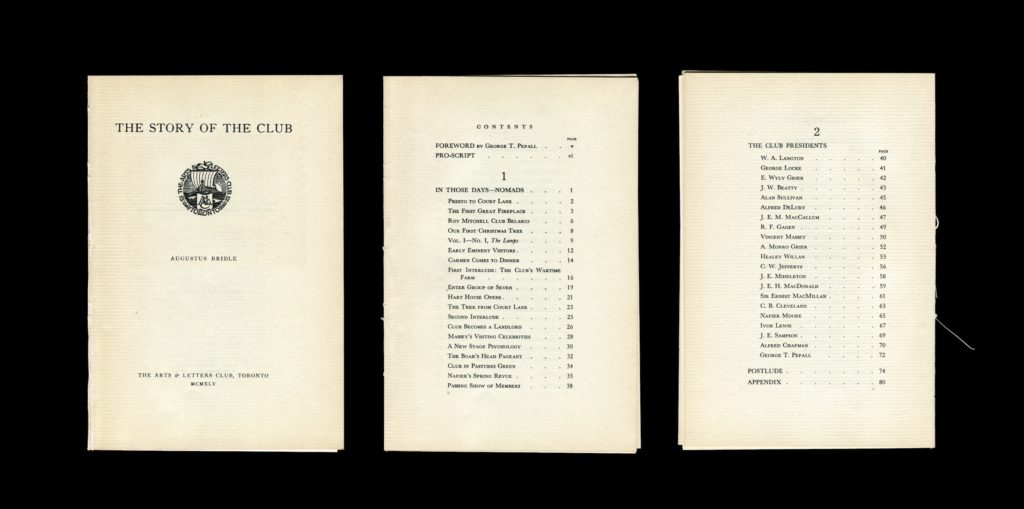

Deanna Bowen, 1911 Anti Creek-Negro Petition From Immigration of Negroes from the United States to Western Canada 1910–1911, 2013. Ink-jet prints on archival paper,

27.9 x 21.5 cm each. Courtesy Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery.

Deanna Bowen, 1911 Anti Creek-Negro Petition From Immigration of Negroes from the United States to Western Canada 1910–1911, 2013. Ink-jet prints on archival paper,

27.9 x 21.5 cm each. Courtesy Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery.

Maya Wilson-Sanchez: Many of the archives we visited for this project have an interest in caring for the material past of those in the social network of the (mostly) white men we researched. Their influence on the political, economic, social and cultural fabric of Canada, an influence which began in the 1910s, ’20s and ’30s, is preserved in these material archives made up of mostly printed matter. What became clear as we learned more about this group was that they were constantly thinking about their influence and how they would be written into history. They took up this job themselves, writing books and articles about one another and their work, and canonizing themselves in turn.

The general mechanism of archives also influences what is considered valuable, what is considered evidence and what is considered (materially speaking) an “archival object.” Before this project, my experience in archives consisted mostly of researching the pasts of women, racialized and queer people—people whose histories have been neglected, ignored and omitted from the archives. The difference between that work and researching these white men quickly became apparent. For the most part their histories have been written, preserved and cared for on their terms. The archive largely reproduces whiteness and settler colonialism, and in doing so it omits not only other parts of history, but also other ways of understanding what history is made up of. It privileges linear narratives of time and certain types of material, such as the written word and printed matter. For those of us whose histories don’t follow these conceptions or require material parameters for “proof” of the past, we often get left out. When we want to reclaim our history, we’re asked to provide evidence within the context of what is acknowledged as proof within the established parameters of the archive. This leaves out songs, textiles, dancing and so many other forms of remembering the past that, at least for now, are largely unsupported by most archives.

Cover of Vincent Massey’s The Making of a Nation (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1928). Collection of Deanna Bowen.

Cover of Vincent Massey’s The Making of a Nation (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1928). Collection of Deanna Bowen.

Deanna Bowen: I agree, there are hierarchies in the archive. Most Indigenous and racialized people are relegated to what theorist Allan Sekula would call the shadow archive. I’m using his terminology loosely here but the point is that, in the archive, there are certain people who merit remembrance and there are others who are not documented or who are wilfully forgotten, which is particularly the case for Black Canadians.

I think these men were certainly wielding their power and influence, but they were doing so in a classist social environment that was already built on the shared values of their fathers and grandfathers. This social context affirmed their sense of entitlement to (making) the world. Perhaps my issue is a matter of word choice. The historical concerns and self- “consciousness” of these men became explicitly evident in our review of their archives. And in my mind, the entitled mindset we are both speaking to is really more in keeping with good old-fashioned white Imperialist ambition. While many of these men were born into networks of wealth and privilege, the Canada they envisioned is not fantastic or of a certain time or age. They are no different from the contemporary white “elites” who exist today, and the mindset, political ambitions and rhetoric of 1920s Toronto is frighteningly comparable to the everyday rhetoric and machinations of self-referential “liberal” politics today.

Bringing this down to earth facilitates an important discussion about our very close proximity to these kinds of networks. This matters because there is a strong tendency for Canadians to distance themselves from these uglier, genocidal contextual realities by insisting that these people and their collective endeavours—good or bad—are exceptional to the normative fiction of Canada’s social tolerance and progressiveness. The benefit of normalizing these players and their skewed ambitions is that I come to better understand the practical and political implications of these material archives we have been digging through. With this normalizing perspective, the performative archival retrieval processes that I described earlier seem so campy. It’s just so extra.

We can expand this to consider that the physical archives we reviewed revolve largely around the cultural preferences of these men and their very specific ideas about the use of the arts as well as other mundane, yet widely accessible, mainstream outlets like department stores and newspapers as a means to develop a particular kind of nation. In an effort to avoid the (far too) common practice of reading these archives in a timeless vortex (and outside of other histories), I think it’s important to acknowledge the broader social-political climate that these men were functioning in.

The Ku Klux Klan and other far-right groups were at their peak across the nation in the mid-1920s, the same time this network was gaining momentum. (See, for example, the 2016 paper on right-wing extremism in Canada, produced by the Canadian Network for Research on Terrorism, Security and Society, a policy think tank.) Really, conscious or otherwise, none of this is benign. All of this does the work of dissemination…perhaps influencing the public.

Maya Wilson-Sanchez: When white supremacy is normalized, it becomes mundane or everyday, and that is when it is the most dangerous. One of the things that became apparent during our research is that the Canada these artists, writers and academics envisioned in the 1920s is alive and well. Canadians still largely look up to men like Lawren Harris, J.E.H. MacDonald, Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Vincent Massey while holding on to the narrative of Canada as progressive, peaceful and generous. There is a great resistance in acknowledging, for example, Canada’s involvement in the slave trade and its centuries of genocidal acts toward Indigenous peoples.

During one of the weekly tours of the “God of Gods” exhibition, an older white man asked me and one of the gallery staff, “Well, why aren’t you also showing all the good things we did with Indigenous people? You need to show both sides.” Not only is there a resistance to this gruesome past, but there is even more resistance from some (white folks and others) in understanding our collective, ongoing complicity. Deanna, last summer you said to me, “I never want to make a work that white people can consume and walk away from.” I think this is what you and I have tried to achieve in researching this exhibition.

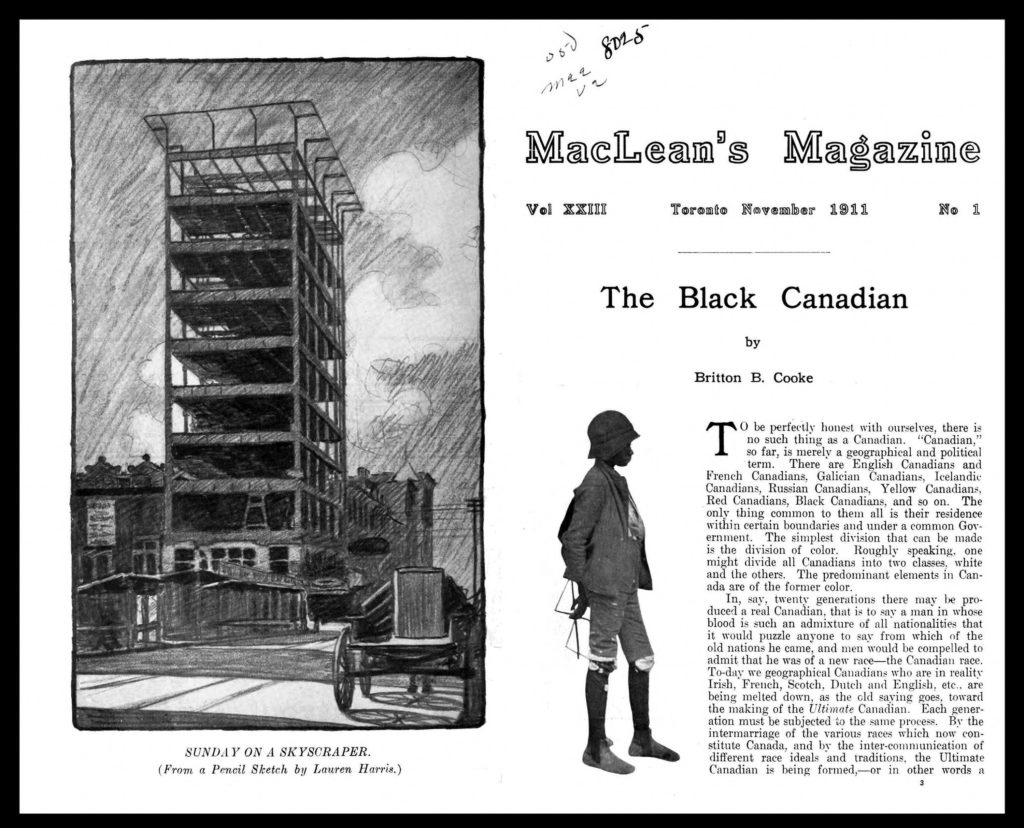

Britton B. Cooke, “The Black Canadian,” MacLean’s Magazine, vol. 23 no. 1, November 1911. Caption underneath illustration opposite cover page reads “SUNDAY ON A SKYSCRAPER (From a Pencil Sketch by Lauren Harris.)” Collection of Deanna Bowen.

Britton B. Cooke, “The Black Canadian,” MacLean’s Magazine, vol. 23 no. 1, November 1911. Caption underneath illustration opposite cover page reads “SUNDAY ON A SKYSCRAPER (From a Pencil Sketch by Lauren Harris.)” Collection of Deanna Bowen.

Deanna Bowen: I try to make works that deny white audiences the opportunity to perform, and then to immediately dismiss, their understanding of Canada’s racist history. Performances of high-minded, earnest regard followed by prompt dismissal are the most common responses to anything that deviates from ideas of Canada as a tolerant, not-racist nation—especially and always in comparison to the US. It’s a stunningly delusional mindset divorced from facts or logic. It took me quite some time to get clear about the underlying intentions of this repressive strategy that masks deep white Imperialism via instant amnesia and/or aggressive arguments about a “socialist” society. Health care and gun control are always mentioned. I do my best to make work that factors this faulty, illogical psychology into the equation. This has resulted in a practice and body of work that relies on the archives of white men and women (acceptable evidence) in order to make my case and then get down to the nitty gritty of naming the racism that this performance of the earnest Canadian is meant to obscure.

Maya Wilson-Sanchez: Part of our work looked into how Indigenous cultures were used as a resource for developing the cultural imaginary of Canada. Some of the men we researched were interested in getting to know various Indigenous communities in Canada, while creating a national narrative based on Indigenous genocide. Famed Canadian anthropologist Marius Barbeau, who worked with Americans Edward Sapir and Franz Boas in the style of salvage anthropology, recorded and filmed West Coast Indigenous communities with musician and conductor Ernest MacMillan. Barbeau and MacMillan were elites; both were members of the Arts and Letters Club. MacMillan was later knighted by King George V and was dean of the faculty of music at the University of Toronto, while Barbeau worked at the then-named National Museum of Canada for most of his career.

In 1929, MacMillan published Three Indian Folk Songs, in which he transcribed and arranged three songs that were recorded by Barbeau and translated by deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs Duncan Campbell Scott (also a celebrated poet). Scott led the department during the height of the residential school system and had a number of objects in his personal collection that were confiscated from West Coast communities through the potlatch ban. In the introduction to the accompanying pamphlet, MacMillan wrote, “The ancient melodies of the West Coast tribes, still surviving in the memory of the elders, seem to have little interest for the majority of the younger generation, and would without a doubt be totally lost in the course of thirty or forty years but for the energy and enthusiasm of a handful of collectors.” They were certain that Indigenous people and cultures would become extinct, and did their work with this assumption in mind while ignoring their own complicity. (Lynda Jessup co-edited the 2008 book Around and about Marius Barbeau: Modelling Twentieth-Century Culture and has written extensively about this in articles and book chapters; Leslie Dawn discusses this in National Visions, National Blindness: Canadian Art and Identities in the 1920s, from 2006; and Dylan Robinson’s new book, Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies, forthcoming in 2020, also in part discusses Barbeau.)

Barbeau and MacMillan were interested in Indigenous cultures but not Indigenous people or their well-being. They were working just after European avant-garde/primitivist artists had started to look to non-Western cultures for affinities and inspiration—some might say influence. As Picasso was collecting African masks, André Breton was collecting masks from the West Coast, which were taken from communities through the potlatch ban upheld by Scott. The primitivism found in the play The God of Gods is mirrored in the cultural creation of Canada to some extent. We found that for many of the men we were researching, the relationship with Indigenous people was, at best, extractive. They took what they wanted and left. And they brought their findings to be studied and used as sources of inspiration for white artists, musicians and academics in order to develop a uniquely Canadian aesthetic, one that positioned Indigenous peoples in the past, and European Canadians as the ones tasked with developing the future.

You can see this in Barbeau’s 1927–28 exhibition “Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern,” held at the National Gallery of Canada and the then-named Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). It showcased work from various nations in the West Coast, as well as work from European Canadian artists including Emily Carr and members of the Group of Seven. In the exhibition catalogues for both Ottawa and Toronto, Eric Brown, then director of the NGC, wrote that “The disappearance of [art from the West Coast] under the penetration of trade and civilization is more regrettable than can be imagined…. Enough however remains of the old arts to provide an invaluable mine of decorative design which is available to the student for a host of different purposes and possessing for the Canadian artist in particular the unique quality of being entirely national in its origin and character.”

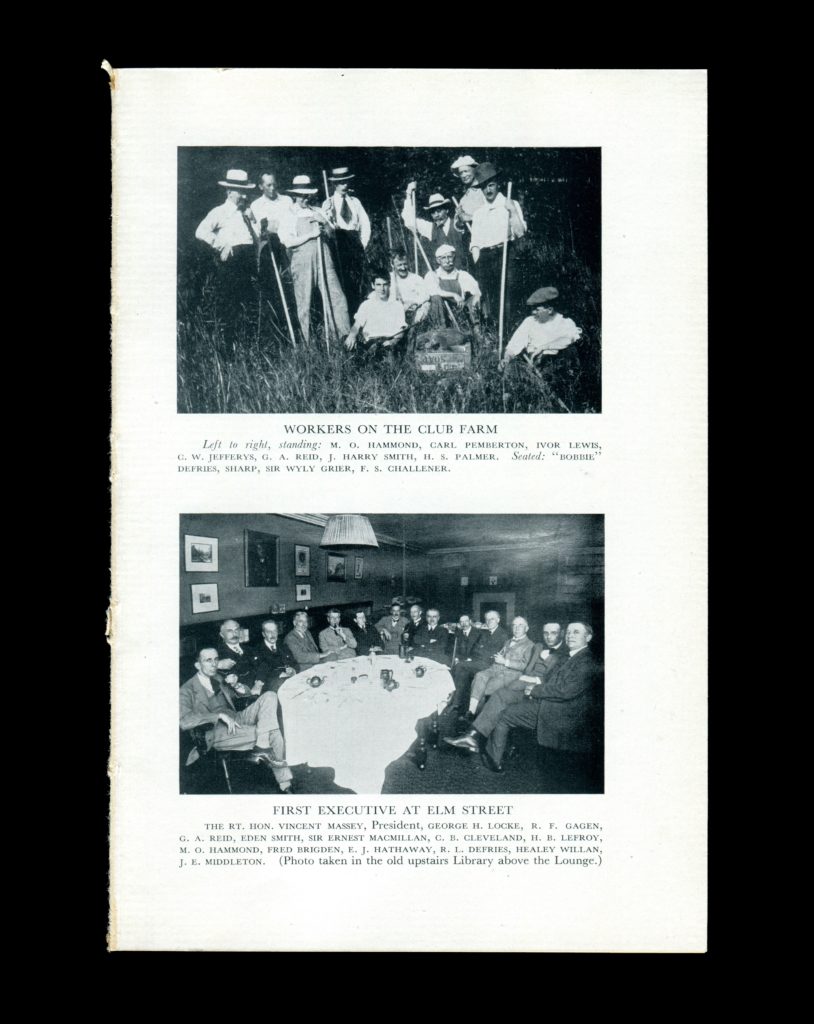

“Workers on the Club Farm” and “First Executive at Elm Street” in Augustus Bridle’s The Story of the Club (The Arts and Letters Club of Toronto, 1945). Collection of Deanna Bowen.

“Workers on the Club Farm” and “First Executive at Elm Street” in Augustus Bridle’s The Story of the Club (The Arts and Letters Club of Toronto, 1945). Collection of Deanna Bowen.

Deanna Bowen: Yes, and the social-political ecology we are all living in now is the future Canada these men envisioned. You can see the extended outcomes of their consciously nurtured, unwaveringly certain nationalist vision quite clearly in our cultural lives every day. Artistic/general director Ravi Jain and managing director Owais Lightwala of Why Not Theatre co-authored a speech delivered to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage in June 2019. It addressed the impact and ongoing influence of this genocidal certainty that informed Vincent Massey’s cultural policies from the mid-1920s through to his Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences report (also known as the Massey Report) in 1951. (Demonstrating the reach and longevity of networks and influence, it happens that MacMillan contributed to the Commission by writing a study on the state of music.) Jain and Lightwala illustrated the ongoing influence of this certainty to Canadian Heritage by reminding the Committee that the Commission and its related cultural institutions— the Canada Council for the Arts, the National Library of Canada, the National Gallery of Canada, the National Film Board and the CBC—are built on an ideological foundation that in the 1951 Massey Report insisted:

…since the death of true Indian arts is inevitable, Indians should not be encouraged to prolong the existence of arts which at best must be artificial and at worst are degenerate…. The impact of the white man with his more advanced civilization and his infinitely superior techniques resulted in the gradual destruction of the Indian way of life. The Indian arts thus survive only as ghosts or shadows of a dead society. They can never, it is said, regain real form or substance…. Indian art as such cannot be revived.

To be fair, the practical interpretations of these ideas do evolve as institutions grow, but the initial ambitions (for a white, British Canada) are deeply embedded in the country’s cultural narrative and national fabric. In my mind, Jain and Lightwala’s revelation of this passage from the Massey Commission, and our combined research efforts for the “God of Gods” exhibition, are strong examples of the profound (and painful) corrective potential that comes from their, and our, fresh eyes in the archives—archives that document this network of important white Canadian (mostly) men.

Maya Wilson-Sanchez: Exactly. Your video Deconstructing The God of Gods: A Canadian Play (2019) stages a conversation between Indigenous artists and curators John G. Hampton, Peter Morin, Lisa Myers, Archer Pechawis, cheyanne turions and yourself, during which you all discuss The God of Gods, the Group of Seven, the ongoing effects of colonization and how things have not changed enough. In that work, Morin, a Tahltan artist, says, “The Group of Seven paintings actually make me feel like I am suffocating…. Right now those paintings make me feel like I want to die…. They’re not beautiful. We are beautiful, and those artists missed out on the possibility of making beautiful paintings because they left out our bodies.” This erasure is part of the legacy of the Group of Seven, of Barbeau, of MacMillan, of Scott, of the Massey Commission, and much more.

What we’re tasked with today is how to move beyond this. It’s been 100 years since the Group of Seven had their first exhibition; on this centenary, we need to ask what parts of this national legacy are worth keeping and what needs to be critically questioned. Our research involved so much of the past, but I also remember us talking about our hopes for the future. Our intergenerational and trans-cultural collaboration taught me a lot about solidarity, and what it means to create something together and to care for one another while doing very difficult work. We need to do more of this, collectively, in order to imagine and create a new legacy.

Deanna Bowen: Indeed.

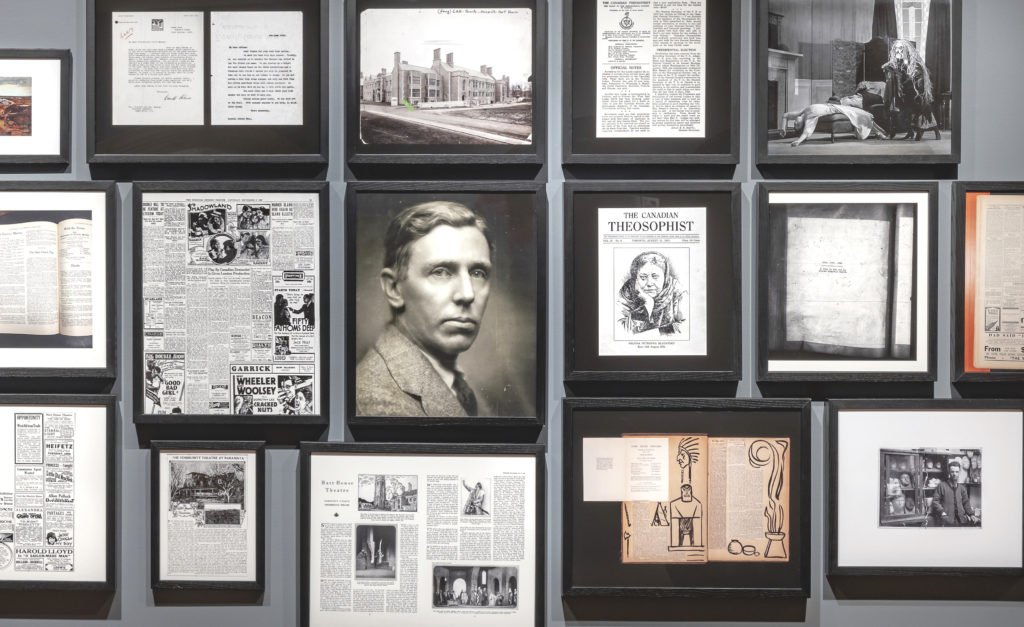

Deanna Bowen, “God of Gods: A Canadian Play” (installation detail), 2019. Courtesy of the Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Deanna Bowen, “God of Gods: A Canadian Play” (installation detail), 2019. Courtesy of the Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.