In the very early morning of November 9th, I was at Toronto’s Double Double Land with seven sad-faced people, waiting for the results of the American election to be different.

The rain outside was lukewarm, making the air heavy enough to dampen panic. A wobbling, young, drunk man said something like, “I mean, he’s no worse than any other politician. And art’s going to get amazing. Punk’s going to come back.”

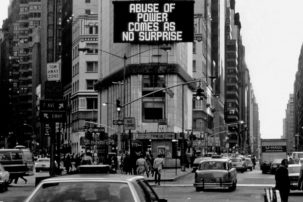

Art’s going to get amazing; punk’s going to come back. Sentiments like this popped up in Facebook comment threads when Rob Ford was elected mayor of Toronto several years ago. People said it again when we snowballed four years of Stephen Harper into eight. Art and punk, two super-brothers hiding in civilian disguise, waiting to save liberals everywhere from real political crisis.

But art doesn’t need a political pressure cooker to thrive. Yes, it will survive any climate. Art pushes its head through the concrete of refugee camps, residential schools and prisons. Even when we have nothing, we still make art. It’s the product of the human compulsion to make sense of our situation.

In our compulsive quests, we use art, turning to it in times of crisis. It’s easy to believe that because art comforts by reflecting us at our most desperate, the really great stuff must be created by people mired in the same desperation. It’s true: lots of incredible work is built on turbulent emotional foundations. But being able to explore, then express, that turbulence in a healthy, skilled way is often the product of community and support.

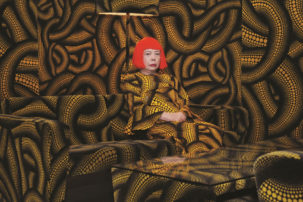

The 1960s and 2010s in America were soaked in revolutionary work, from Yoko Ono to Young Jean Lee, and were presided over by democratic liberals. The Kennedy administration planted the seeds for the creation of National Endowment for the Arts, and Kennedy and Obama frequently and visibly kept company with some of America’s most popular artists. No government has ever served the arts as much as they serve business and the military, but governments that serve the arts even just a little bit can make a big difference in whether individual artists can do their work. Attacks on the NEA in the 80s and 90s—including slashing of funds under a Republican-held Congress in 1996—meant trouble for arts organizations across America, but it was a disaster for individuals and smaller arts organizations that didn’t have access to large pools of private donors. It’s a lot easier to finish your play when you don’t have to pawn your computer to pay rent.

I’ve been an artist-in-residence at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre since 2010. In the fall of 2013—in the last years of Stephen Harper’s term—the theatre’s then-34-year-old Rhubarb Festival lost its funding from the Department of Canadian Heritage.

A letter addressed to Buddies’s artistic director Brendan Healey said:

“The Government of Canada’s ongoing objectives are to find projects designed to deliver measurable and tangible results, to optimize available funds, and to meet the needs of Canadians. It is within this context that, on behalf of the Honourable Shelly Glover, Minister of Canadian Heritage and Official Languages, I regret to inform you that your application has not been approved.”

How had Canada’s longest-running new works festival, hosted at what is billed as the largest queer theatre in the world, which had nurtured hundreds of playwrights, including 25 per cent of the total winners of the English-language drama Governor General’s Award, somehow failed to produce measurable and tangible results for the Canadian government?

It’s a lot more plausible that Shelly Glover and her staff couldn’t see how the festival met the needs of Canadians. Rhubarb seeks to program “projects that fight the normative, projects that ask big questions, and forms that ask the impossible.”

Previous Rhubarb works are truly walks through what James Baldwin has called “the great wilderness” of artists’ selves. But when the forest looks completely unrecognizable to the conservative viewer, that wilderness looks unconquerable and maybe not all that important. My darkest, most disquietingly comforting, most confusing, most confrontational experiences with art have been had either as a part of or as a spectator at the Rhubarb Festival. It’s an institution of provocation. I’ve seen Ulysses Castellanos swing a live chainsaw by its cord after decapitating hundreds of stuffed animals. I’ve seen Keith Hennessey sew his skin to my friend’s sweater. I’ve written a text and been shocked by its violence when I sat in the audience and watched my collaborators perform it.

None of the work at the Rhubarb Festival might meet the needs of Canadians as Glover and her staff understood them. A cursory look at the projects that did get Canadian Heritage funding in 2013 includes many cultural festivals, a handful of county fall fairs, and something called the Christkindlmarket in Nova Scotia, which, to be fair, sounds delightful. These are events that can probably really clearly articulate exactly why they’re useful to the communities they inhabit.

It’s a problem for events like the Rhubarb Festival or SummerWorks (which also didn’t get its Canadian Heritage funding for a time under Harper) because it’s often hard to see, at the moment of its inception, how art meets any needs at all. But when the government in power can’t see themselves reflected in the work an artist makes, that artist’s value decreases. They get less money, less support and their communities are forced underground.

It’s even possible that the kind of art that’s not immediately understandable, the kind that gets its funding cut, the kind that reminds us of the unknowable wildness at our cores, is antithetical to all government. Government is doing everything it can to “civilize” us. Every time we’re confronted with work that’s incomprehensible or elicits a confusing reaction, we’re reminded “civilization” is just a goal some have.

Buddies survived the Conservative government’s blow to their funding. They managed to do remarkable work, like they always do. In 2013, they won the Dora for Outstanding New Play for Tawiah Ben M’Carthy’s Obaaberima. Rhubarb alums Jordan Tannahill and David Yee continued the tradition and won the 2014 and 2015 Governor General’s Awards. Survived and managed is what Buddies did. The festival was scaled back—fewer projects, and smaller—but it still happened. When you take any group of artists, no matter how remarkable or resilient, and cut the cord of their support systems, they’ll suffer. But artists will keep making work, because that’s what they’re compelled to do.

As for art’s supposedly redemptive sidekick, punk, it never went away. 1970s punk was the go-to platform for frustrated (and largely male) white suburbanites—so of course that young drunk man I encountered found solace in it. But there is an evolved and expanded definition that pre- and post-dates this sociocultural coding. To me, an enduring tenet of punk (or whatever you want to call it) is shamelessly inhabiting your identity even when it’s dangerous. That’s something many people of colour, queer and women artists have been doing this whole time, no matter what government is in power. Punk will live as long as it has to, whether it looks like Sid Vicious or Mykki Blanco.

On January 6th of this year, Buddies in Bad Times got notice that their Canadian Heritage Funding had been restored. Buddies director of development and communications Mark Aikman didn’t want to say change in government was responsible for the restoration, but he was happy the funding was back. According to the theatre’s website, Rhubarb will be “hiring more artists, paying artists more, offering more accessibly priced tickets, and just generally bringing you another great fucking festival.” Reading that announcement made me smile, but big parts of me are wary of any government’s commitment to the arts. I want to depend on them, but we’ve seen strong commitments evaporate.

The worth of art isn’t always easily appraised by every eye. Anyone who’s written a grant understands the unique exhaustion of trying to translate emotional abstractions into a clear value proposition. There’s value, but there’s not always language to describe what moves in you when something’s begun to lay a path in your personal wilderness. It’s important to find and preserve the communities that help us make the work inside us. We’ll need it later, even if we don’t know why now.

Art thrives when artists are valued. Governments that create policy to ensure artists have to make work in crisis doesn’t mean that work is more valuable because the artists are fighting for their voices. It might seem more urgent, but urgency is the product of desperation. I try to imagine what artists could do if they didn’t have to fight so hard.

Aurora Stewart de Peña has had plays produced in the US and at home. Her published work has appeared in Little Brother and the Puritan.

Donald Trump speaking at the 2013 Conservative Political Action Conference. Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr

Donald Trump speaking at the 2013 Conservative Political Action Conference. Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr