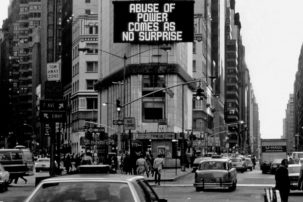

On October 27, 2016, contemporary-art organization Rhizome premiered its much-awaited Net Art Anthology. An online-only exhibition spanning 100 works uploaded over the course of 100 weeks, the Anthology undertakes the necessarily tricky task of restoring and restaging a selection of artworks made specifically for the early World Wide Web.

The goal in reintroducing many of these incipient Internet artworks to Web 2.0 is, as Rhizome puts it, to document the ways in which the Internet has “[given] expression to emerging subjectivities [and] model[ed] new forms of collective cultural practice…presenting exemplary works in a field characterized by broad participation, diverse practices, promiscuous collaboration, and rapidly shifting formal and aesthetic standards, sketching a possible net art canon.”

In Rhizome’s own words, making a case for Net art’s canonicity is as much a matter of the social as it is the aesthetic, offering a digital archive that attempts to return the body to the machine.

By some unhappy twist of fate, October 27 was also the day that Vine publicly declared it would be “discontinued” as a six-second-looping video-sharing platform. Vine had existed for three years as a significant incubator for humour, launching a stream of memes and birthing the careers of some legitimate stars, including Canadian singer-songwriter Shawn Mendes.

However, the news did not arrive as a total shock. For one, the app had been marred by rumours of financial disputes with popular users. Career Viners, such as Amanda Cerny, King Bach and Marcus Johns, had all apparently stopped uploading content to the app due to Vine’s unwillingness to negotiate lucrative contracts, signalling an impasse between user labour and social-media platforms that critic Christopher Glazek has raised in a widely shared public Facebook post.

Moreover, the past year saw Vine’s primarily teenaged user base making a steady exodus toward other time-bound video platforms, such as Snapchat and musical.ly, and embracing the story and video functions added to Instagram. Vine’s statement on the matter, announced via an entry posted to Medium, the online amateur-publishing site owned by their common parent company Twitter, was brief and suitably inconclusive. The statement offered no substantial clues on the future of the app, didn’t confirm any reasons for its planned closure, and details on the terms and conditions of its end were scant.

The sole promise made was that users would be able to download and access their own content and that a copy of the site and its billions of videos would remain available online “because [they] think it’s important to still be able to watch all the incredible Vines that have been made.”

In the wake of the outrage surrounding the mysterious disappearance of artist Dennis Cooper’s literary blog at the hands of Google this past July, both Vine and Rhizome’s statements appear to be affirming the importance of continuing to see what might otherwise be lost to the sands of digital time. However, this is where the coincidence of their archival thrusts ends. Peering back at the legacy of Net art and the confluence of our online and offline worlds (if, indeed, we can even claim such distance any longer), the need to make accessible many of the pioneering works that have otherwise been lost to the instability of the early Internet seems worthy, even vital.

It’s important to know where we come from.

Vine’s archival address, on the other hand, does not square with the various people who have used the app for many reasons. Broadly speaking, many Viners likely do not view the preservation of their work as a central concern, if only because Vines have always already existed elsewhere, either as videos on users’ phones before or after being posted, or as a part of “Best of Vine” YouTube compilations.

Additionally, beyond the fraught (but in no way unprecedented) practice of a media company limiting user access to content while simultaneously possessing it, what felt most unsatisfactory about Vine’s message was the language it used to address those who frequented the app. In their announcement, they speak of Vine’s users on two registers: the “millions of people who have turned to Vine to laugh at loops” and “you,” the individual “who came to watch and laugh every day.”

Grossly, if not deliberately, missing the point, its users are reduced to an undifferentiated mass that has accessed and enjoyed Vine according to a singular purpose: “to laugh.”

What Vine gets right in its statement, although perhaps unintentionally, is that people came to see “creativity unfold” on the app. Unfold there it did, and not only in the hands of Vine’s capital-C creators of the King Bach variety. Their reassurance that they will be moving ahead with plans toward closure in “the right way” is a tactful way of initiating users to an imminent disappearance, a gesture that recognizes the legitimacy of the content of any user.

Even so, Vine’s insistence on laughter and comedic content being the sum-total of Vine’s appeal is an incomplete picture of its emotional and artistic significance.

Jeff Bierk, a Toronto-based photographer and lover of Vine, reflects on the particularity of Vine as a platform that provided a space apart from other networking locales like Facebook or Instagram. As he told us, “Vine is this beautiful, deep hole I come to from time to time when I really want to check out. I love video, and for me there was such freedom in Vine’s limitation of the six-second loop.”

To call a supposed restriction a “freedom” proposes a contradiction that feels true of any art form, wherein a constant structure or set of rules is the germ of further experimentation. This is especially evident with the technics of Vine, its specific mode of interface being a point at which accessibility and innovation collide. It invites video makers who are “unskilled,” or very young, or lacking in economic means, or for whom the vast open-endedness of YouTube might be a deterrent from producing work of any sort.

Bierk indicates a nostalgic preference for a certain aesthetic that Vine enabled in its early period, when people were still discovering what it was all about, explaining, “I think it was the best at the start, when it was more about tapping out something cool—the choppy stop-motion clip.” The platform’s built-in editing features offered users the option of making cuts, a simple recipe for an imaginative, Georges Méliès–style illusionism: tapping the screen while a friend jumped up and down made them appear to float through space. Single takes had their magic too, such as when you caught a weird moment by chance or an unexpected reaction from someone, from then on committing that accident to an infinite loop.

Whether painstaking or fortuitous, it involved an energy that happened between people, a form of social creation resembling play, whose various forms had different shades of humour. But, as Bierk notes, it was also beautiful.

Much of Bierk’s photographic work puts into focus people made invisible by society because of their struggles with addiction. Since they are his actual friends, the faces of the same folks naturally show up in his Vines, except now moving, talking, joking and hanging out. More significantly, there is a thematic kinship between Bierk’s work and the way Vine came to operate—a shared sense that art comes out of being within a community.

The fact of the matter is that as far as content platforms go, Vine was unique in its social orientation.

As Jazmine Hughes writes in her poignant elegy to Vine as a stage for black humour, the app “offered something in between [other social media outlets]: a place for people to see you, even people who didn’t necessarily know who you were…Vine didn’t privilege traditional celebrities—its stars grew organically without the benefit of expensive equipment of high-profile connections.” As a result, the platform became a hotbed for viral creativity authored by typically marginalized groups, especially black teens. Many black-originated memes that entered into wider parlance, such as “on fleek” and “what are those??” originated on the app.

In addition to its significant black usership, other communities otherwise absent from mainstream media were able to find purchase on Vine: furries, Southerners, amateur musicians, twin boys from Pasadena with a penchant for vaping.

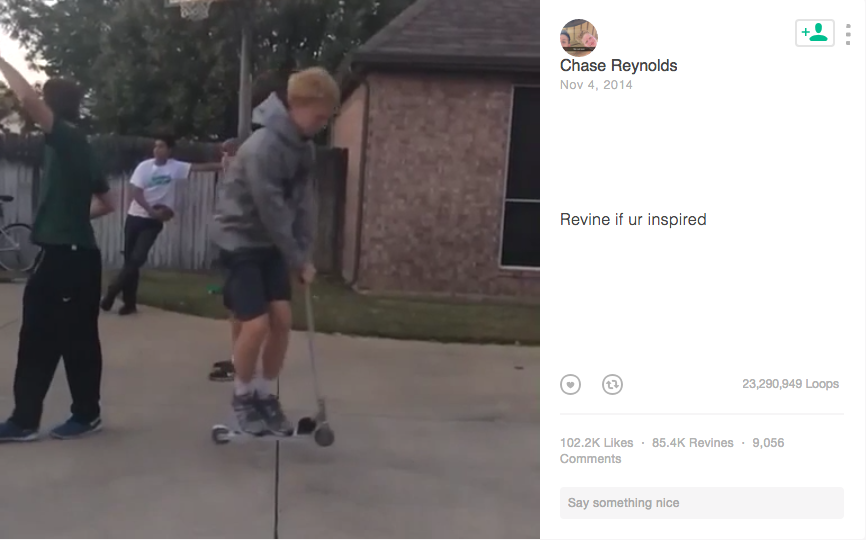

Vine’s essence originated in the aspects of its interface, but ultimately became much more about collaborative work. The users of Vine generated their own memes, editing Vines together beforehand and uploading them to the app afterward, creating a joke for Viners that sometimes reached those in the wider world. A boy hops his razor scooter over the crack in the sidewalk in slow motion while Rich Gang’s “Lifestyle” plays. “Revine if ur inspired” reads the caption, and that is exactly what people did, responding to a sarcastic joke that they were unsarcastically inspired by.

Many of the memes and branches of humour that thrived on the platform were resplendently weird and often unnervingly moving, treading a slippery boundary between joy and melancholy that became increasingly intense with every video loop. Laughter here served not only as an individual outlet, but also as a bridge for public empathy and recognition.

Vines of two young friends greeting one another on FaceTime, a dog’s face visible through a passing car window set to Fleetwood Mac, and a teen girl pretending to drive her mother’s car all elicited earnest laughs and tears that were shared by the millions of users who watched and revined them. Comedy has always formed a social bind for communities.

By the time Vine added the “remix” function, a user could take the audio from a Vine and apply it to a new image on the spot; as always, Vine had amped up the accessibility of what it observed was already being done by users. Six seconds of audio used over and over again could gain its own independence: a little girl’s voice singing the misheard lyrics of Frank Ocean’s “Thinkin’ Bout You” begot other videos of people lipsyncing “A potato flew around my room.”

Besides its user-friendly advantage, the feature incidentally created a trail between Vines that tracked an audio clip’s journey all the way back to the original. The trace was available to be followed backwards in a tangible chain as innovation moved forward, helpfully representing the way that these works all came from each other, distorting a sense of individual ownership. This is precisely the friction and vitality of the app, its way of achieving connection through circulation—in short, its social significance—that Vine left out of its speech.

In the wake of the announcement, it is hard to decide whether to refer to Vine in the past or present tense, to say if it’s a thing that “is” or a thing that “was.” The technical platform is still intact, but the community has left. The teens who gained popularity over the app, like Viner “chloe lmao,” responsible for the viral “Who is she” has renamed her account “twitter/ig: @contrachloe.”

Similarly, many other Viners have changed their screen names to direct their followers to the safety of other social platforms before this ship totally sinks. In an Instagram caption, chloe lmao offers an earnest commemoration of her experience: “Throughout the past two years, I have met some of the most amazing people, been to the most amazing places, heard the most amazing stories, and gotten everything I could’ve ever wanted, all because of an app.” For these teen users in particular, Vine transcended the app itself, taking place in chat conversations, meet-ups and conventions like Vidcon. In a sense, such statements put a lot of emotional weight on the app while making it seem smaller, snowed under by everything that came out of it.

The Internet, with its inbuilt hierarchies of grief, has responded to Vine’s inevitable disappearance in a curious way. When Cooper’s blog disappeared, devoted readers and art-world commentators angrily scrambled to his defense, claiming a “sinister” act had been committed and working tirelessly to restore its contents to the web. Similarly, the Net Art Anthology is the result of a concerted outpouring of digital and emotional labour, witnessing the return of lost Net art artifacts to their “proper” place, so to speak. In Vine’s case, the announcement that a platform presided by a profoundly media-literate but otherwise culturally marginal user base was instead met with a reluctant acceptance of its passing. Marked by an overwhelming sadness rather than outrage, few substantial calls to overturn Vine’s decision and save it from its unlucky fate were made. That day, most took to Twitter to post a selection of their favourite Vines, not necessarily for posterity’s sake but in order to relive them one more time, together.

// <![CDATA[

// ]]>

In one of these tweets, critic Chris Randle included a link to an untitled Vine made by the user lau coo. In the clip she wears a grey Snuggie, and anxiously flails her body in place while the refrain from Broken Social Scene’s “Anthems For a Seventeen Year-Old Girl” plays over top. An emotional distillation of what Vines could and did do, it’s nearly perfect, at once goofy, soaring and utterly devastating.

As Randle captioned the looping video, “[I] have never identified more deeply with any form of art.”

Anastasia Howe Bukowski is a Montreal-born writer and researcher based in New York City. She recently completed a master’s degree in art history at McGill University.

Emma Fox is a Toronto-based writer and student completing her undergrad in cinema studies at the University of Toronto.