Note to the reader: I am using this monthly column to think out loud in public about questions and controversies arising from my current research for a book about contemporary Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995.

Last month, I said that the best Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995 “changed how we imagine ourselves and our place in the world.” Now I want to share 10 works that had that effect on me.

I could have made another list, just as long, with other artists and artworks, but these are the ones that have had special personal importance for me over the years. They touch all of the key themes and strategies that define that period: cultural revival, insistence on the validity of contemporary experience, use of humour, critique of colonial representation and cultural appropriation, claiming space in the public sphere, concern for the land, institutional critique, counter-histories, interrogation of the place of women and exploration of the performance of identity.

These works, and others like them, defined those themes so effectively that it is often difficult to remember just how radical and novel they were when they first appeared.

One of the advantages of list-making is that it forces the compiler to make difficult choices about what is important, helping clarify how one attributes value. The reader, however, is under no such restraint and is free to contemplate—perhaps with frustration—the many favourite works that have been excluded. Therefore, the other value of list-making is contemplation of the inevitable inadequacy of lists and the generation of the desire to think beyond them.

I am hoping that you will take advantage of the comments section to let me know which works would be on your list and why.

Here’s my list, in chronological order:

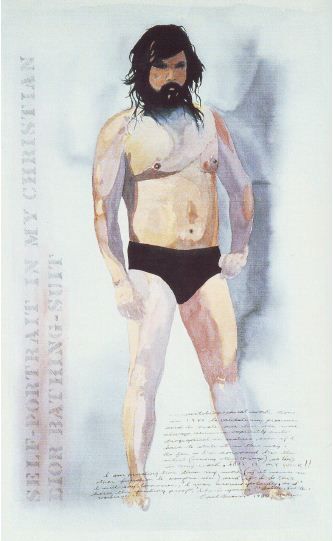

1. Carl Beam, Self-Portrait in My Christian Dior Bathing Suit, 1980

Although I was tempted to include one of Beam’s distinctive time-dissolving collages, I could not resist this defiant self-portrait, which begins our chronology right back in 1980. Beam explained that he was deliberately attempting to subvert the expectations of the art audience of that time. He gave that audience, which would have expected Anishinaabe artists to be working in the so-called Woodland School style (if it expected anything of them at all), a potent dose of contemporary reality. And in watercolours!

In our post-metrosexual world the consumption of designer brands by men is taken for granted, but in 1980, men’s designer bathing suits were marketed primarily to the young and relatively affluent class soon be known as yuppies. A writer discussing this work in the 1980s took it for granted that her readers would understand that an “Indian” would not likely be part of that group.

With his long hippie hair and beard, firm stance and level gaze, Beam seems to be daring us to laugh and, equally, daring us not to. In either case, we are left wondering just what is so funny about an “Indian” in a fashionable bathing suit.

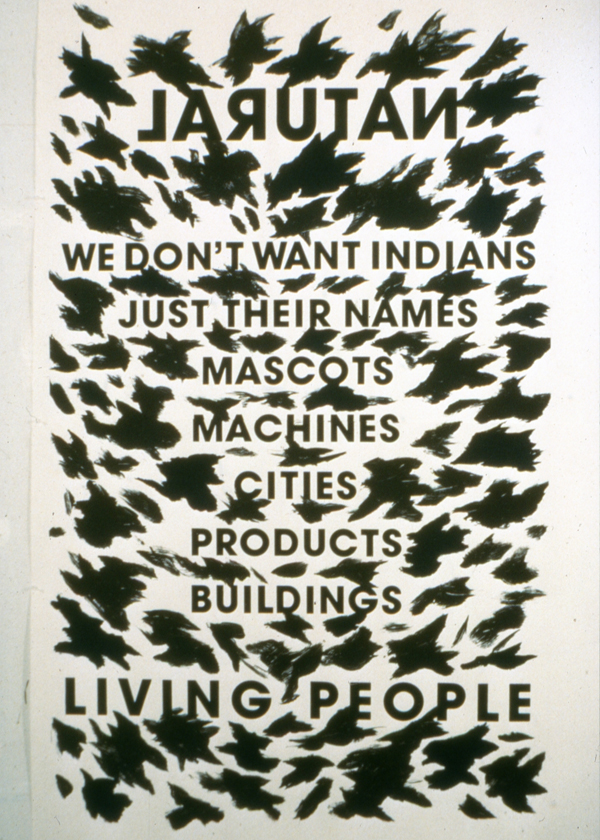

2. Edgar Heap of Birds, Don’t Want Indians, 1982

I hesitated in choosing this early text work over the better-known Native Hosts series, which made powerful claims to public space and counter-histories. But just because that work is already so well known, I tipped toward a more personal choice, a very early work that I have a strong memory of grappling with as a young art student.

It was the first time I had seen an Indigenous artist making conceptual text-based work and, I’m a bit embarrassed to say, that was a bit thrilling in itself. More importantly, however, was the artist’s ability to say so much with so few words, set down in a relentless, convincing rhythm that is jarringly interrupted with the last line.

The work is dark and, sadly, truthful about the appropriation and consumption of the signs and symbols of Indigenous cultures. It begins with the mirror-written word “NATURAL,” suggesting both that it is as “children of nature” or noble savages that we are consumed, and that there is nothing natural at all about this construct.

Indigenous names are wanted but, when we get to the final question—“LIVING PEOPLE?”—we already know the answer. The public sphere into which the artist intends to insert his work has already decided that there is no space for contemporary Indigenous peoples. But the first step in clearing space is to define the terms of your exclusion.

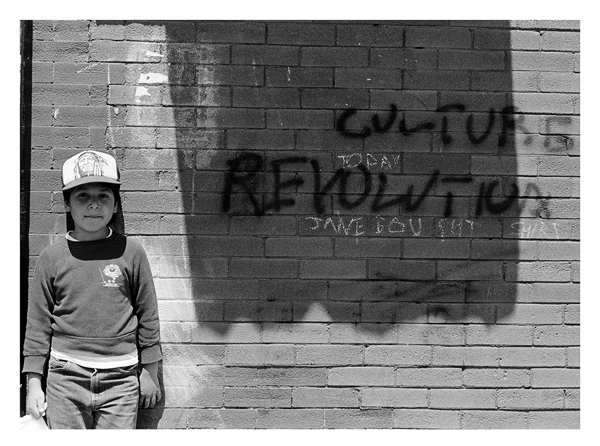

3. Jeff Thomas, Culture Revolution, (Bear Series) Toronto, Ontario, 1984

To me, Jeff Thomas is above all else a researcher. His primary subjects are the history of Indigenous representation and contemporary Indigenous experience: how they sit together and how they can be reconfigured by artistic agency. His primary research tool is a camera, and he is adept at locating his subjects on the street or in the archive. Like the best researchers, he sets himself real questions without presuming to know the answers in advance. As his audience, we follow along and learn with him.

Once he gets onto a subject, Thomas tends not to let go, coming back to worry it time and again, investigating how it looks from each emerging new perspective. I can’t help but do the same looking back at Culture Revolution, the first of the artist’s ongoing series of portraits of his son Bear. Here, Bear is a young boy, wearing an over-sized baseball cap with an Edward Curtis portrait of the Cheyenne leader Two Moons. A bit of graffiti found close to Toronto’s Queen Street points to a revolution that Thomas was both documenting and helping to create.

Bear would eventually grow into that hat. You likely know him as the DJ Bear Witness from A Tribe Called Red. In fact, when I mentioned Thomas in class this year, a student asked, “Isn’t he that guy who is Bear Witness’s father?” I doubt Jeff would mind. That’s what successful revolutions look like.

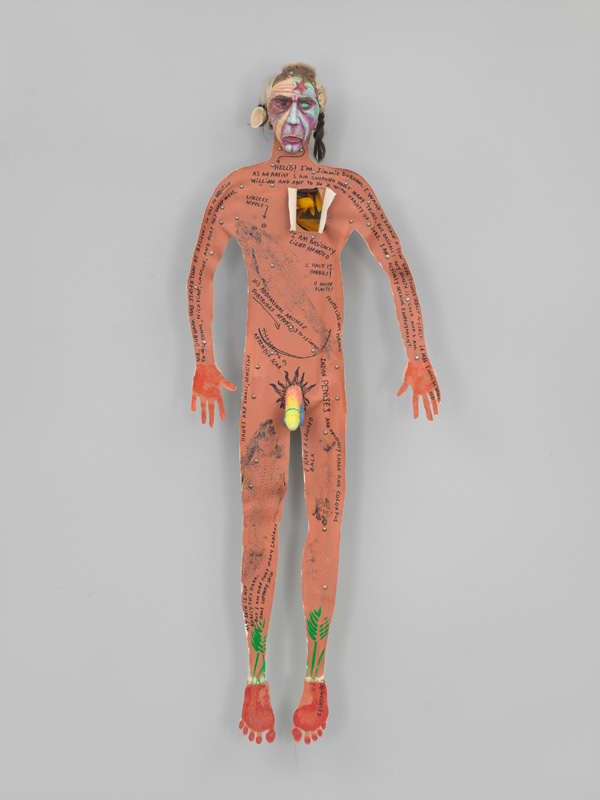

Jimmie Durham, Self-Portrait, 1986. Canvas, wood, paint, metal, synthetic hair, fur, feathers, shell and thread, 78 × 30 × 9 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee 95.118.

4. Jimmie Durham, Self-Portrait, 1986

There are other works by Durham from this period that I find more challenging—the Caliban Codex comes to mind—but none that so concisely distills the critique of the “imaginary Indian” into a single troubled body.

New York Times critic Roberta Smith once claimed that Durham’s art from this period has a “my-roots-my-art earnestness.” Yet Durham’s work from this time is never about his heritage or identity, except insofar as that identity has already been defined by others and is subject to ironic attack by the artist.

Since the beginnings of modernity, the self-portrait has promised a window into an authentic personal identity, but here it provides only, as Jean Fisher wrote, “a masquerade” that “masks a non-identity.”

The body is a flat canvas cut-out with first- and third-person statements about the artist scrawled across it. They range from the silly and mundane: “I have 12 hobbies! 11 house plants!” to the stereotypic-absurd: “Indian Penises are unusually large and colorful?”

The latter claim is illustrated by a large and colourful carved penis. This means that if we pivot from these dubious statements (none of which we can verify) to the three-dimensional elements of the sculpture, we do not move from surface to depth, but only reveal deeper, equally intractable, surfaces. “I am basically light hearted,” a text reads. His chest has been opened up and we can look in, past a few ribs, to see for ourselves; where his heart would be we see a few brightly dyed, red feathers, the sort one might find on a child’s toy headdress.

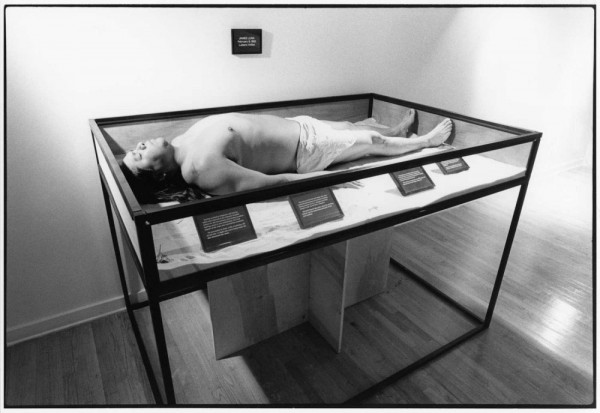

5. James Luna, Artifact Piece, 1987

Institutional critique was a movement that fought on many battlefields, but no sortie was more devastating than Luna’s Artifact Piece. It is a brilliant reductio ad absurdum of museum exhibits of Indigenous peoples (and of attitudes toward Indigenous peoples in general). Luna undertook the performance only twice: first at the San Diego Museum of Man and then, in 1990, for the “Decade Show” in New York. In each iteration, he had himself installed in a museum case along with an exhibit of personal items reflecting the full range of his interests, from beat literature to “Indian music, country and western, old school, pop and rock, new stuff—I listen to it all.”

As he said: “I’m a Native man, born in 1950, who wasn’t born into a tepee, but who was raised in front of a TV. I’m a man who went to college …I want to speak to … everyone who was also born in front of a TV. I want to speak to you as a whole person, and to bring along my cultural side as well.”

The work revealed not only the acquisitive colonial gaze and what Jean Fisher has described as “the necrophilous codes of the museum,” but also the absurdity of its mission to represent whole cultures through a few well-chosen artifacts. And if displaying a live body seems preposterous, we need only point to a history of live exhibits of Indigenous peoples, from Columbus’s first captives to late 19th- and early 20th-century international fairs.

Our impulse is surely the same as an unnamed Indigenous visitor to the exhibition, who Luna claims stood beside him and said, “Get up, hey, get up…”

Edward Poitras, Small Matters, 1988. Nails, wire, paper, instasign. 75.5 x 176 x 5 cm. Collection of the Mendel Art Gallery. Purchased 1989.

6. Edward Poitras, Small Matters, 1988

I was tempted to include one of Poitras’ coyote sculptures here—they are so visually arresting—but this work evinces the subtle conceptualism that is such an important part of his practice. At times, it is characterized by the apparently off-hand gesture or cast aside item that the viewer gradually realizes is full of meaning. And a use of space that suggests both the modern artwork’s expanded claim to wall space and the generous attitude to space in Plains aesthetics. It is a generosity that both demands and rewards careful attention. But don’t let the size or economy of materials fool you. When you lean in to share their intimate space, you will find yourself walloped pretty hard.

The work consists of four pages from Dee Brown’s 1970 bestseller Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, crumpled into balls, text still partially legible, and mounted, widely spaced, on the wall between four protruding flat-headed nails set in a square and wrapped with wire. Beneath each is white text, barely noticeable on the white wall. Brown’s was likely the first popular account of US history to treat Indigenous peoples sympathetically, and it concludes with a description of the massacre at Wounded Knee. A small matter. Barely visible. Each page apparently discarded, then recovered and penned between the nails. White on white, like a late modernist painting. Or like frozen, snow-covered bodies at Wounded Knee.

7. Shelley Niro, The Rebel, 1991

It sounds ridiculous, but before seeing Shelley Niro’s “Mohawks in Beehives” exhibition at Mercer Union in 1991, I did not realize that Indigenous identity could be treated—publicly—as an opportunity for boundary-crossing performative play. I knew that we had a lot of funny people in our communities, and that this sort of play happens regularly in daily life, but being an “Indian” in public seemed like serious business involving predictable performances. Niro changed all that and paved the way for other flamboyant, trope-busting personae soon to be brought on stage by artists like Lori Blondeau, Kent Monkman and Terrance Houle.

According to Niro, this work was an act of liberation born of tension following the first Gulf War and the Mohawk defense of Kanesatake against the Quebec Provincial Police and then the Canadian military (popularly known as the Oka crisis).

Refusing to accept the role of victims, Niro and her sisters adopted various camp personae and, as she puts it, “invaded downtown Brantford.” The photographic record of this excursion was a timely reminder of the power Indigenous women could exercise by seizing control of their own representation and harnessing the plays of desire that drive pop-cultural tropes to new and delightful ends. It would take a heart of stone to look on The Rebel and not be seduced.

8. Rebecca Belmore, Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to their Mother, 1991

Another child of the Mohawk defense of Kanesatake, Belmore’s enormous megaphone is a brilliant piece of agitprop that established her ongoing concern for the vulnerability experienced by those who have been rendered voiceless. Belmore toured this work across the country to literally give voice to many Indigenous communities who were otherwise effectively silenced in the public sphere.

I can think of no other artwork that has mobilized such enthusiastic participation outside the art world, while also resonating, as art, across a vast and often poetic spectrum of meanings. Much of the work that has since been made since with similar participatory ambitions—often gathered under the banner of relational aesthetics—looks desperate and anemic in comparison.

The work is an impressive machine for speaking, and even silent in the gallery, it is never entirely quiet; its constant potential to speak creates rumblings of dissent in each viewer’s mind. But when it is used, it is the artist’s request that speakers direct their utterances toward the land itself that opens the work up in so many other directions. It decenters the state as “hearer” and arbiter of public grievances and places the speaker in a relationship to the land that is simultaneously humbling and empowering. That’s a good combination when engaging in political speech.

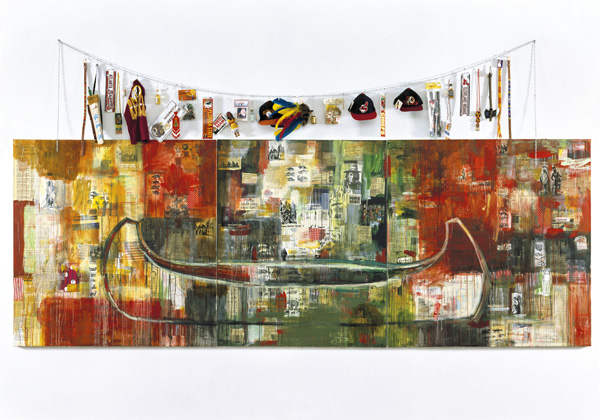

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People), 1992. Oil and mixed media on canvas, 60 x 170 in. Collection of the Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Va. Purchase in memory of Trinkett Clark, Curator of American and Contemporary Art, 1989–1996. © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.

9. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People), 1992

Like Durham’s Self-Portrait, this work is often reproduced because it so successfully condenses a series of important ideas and approaches into a single work. At first glance, it contrasts an icon of Indigenous design and mobility—the canoe—with a string of kitsch stereotyped objects, suggesting the bitter irony that Indigenous sovereignty over traditional lands has been exchanged for the ongoing dehumanization of trivialization and misrepresentation.

As in many paintings from this period, this clash is played out against a collage in which historical photographs and imagery from pop culture struggle and compete to achieve surface visibility. The effect is not only to put alternate histories on the table (the work was one of many attempts to subvert celebrations of the quincentenary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas) but to think differently about history more fundamentally. Here, history is not a linear narrative, but exists in a complex simultaneity with a troubled present.

10. Faye HeavyShield, Untitled, 1992

I first saw this work by HeavyShield in the catalogue for the 1992 Indigenous art survey exhibition “Land, Spirit, Power” and then later in person at the National Gallery of Canada. As soon as I saw it, I was aware that I was in the presence of an important object, yet when I tried to articulate that importance to myself, language seemed only partially up to the task.

I could see the seamless way that she wedded the aesthetics of Plains architecture (and smaller built things) with the austerity of late modernist sculpture. There’s a lovely contrast between banal materials—layers of little bits of newspaper clippings not quite hiding under yellow paint—that convincingly define an elegant shape and are, at the same time, contained within it. There’s a suggestion of functionality that, in the end, can be attributed to no particular function.

In an artistic milieu understandably dominated by works in which recognizable signs and symbols often mauled one another in battles over the politics of representation, HeavyShield’s work established a model for a contemporary Plains visual poetics that functioned with a soft-spoken gravitas. The more time passes, the more profoundly political that seems.

Richard William Hill is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Studies at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver. If you have advice, information, documents or anything else that might help him with his research on Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995, he would be grateful to hear from you: richardhill@ecuad.ca. Thanks to the many people who have already been in touch.

Shelley Niro's The Rebel (1991) is a work that stands as "a timely reminder of the power Indigenous women could exercise," Richard Hill writes.

Shelley Niro's The Rebel (1991) is a work that stands as "a timely reminder of the power Indigenous women could exercise," Richard Hill writes.