When I returned to the conference, and it was finally my turn to speak, I looked out into the crowd and saw some of the most respected tribal leaders in Alberta alongside high-earning Indigenous celebrities and academics. But I saw the students too. This was during the first year of my master’s, where my funding was barely enough to cover my tuition and it came from a personal grant, generously awarded to me by the only Indigenous professor in the department (and one of the only Indigenous professors at the university, at that). I would later find out that virtually everyone else in my completely non-Indigenous cohort had received departmental entrance scholarships. I rolled up to the conference with around $300 in my bank account. I mean, I had just used the food bank at my school only a few weeks before, during a delay in getting my first payout from that grant and after quitting my job to start grad school. Having heard my other Indigenous peers’ stories about living in poverty while attending university, I knew many of the other students in the audience were likely in the same position as I was. And here we were, discussing reconciliation among those perhaps most disconnected from what a healing community would entail. I remember feeling angry.

“Annie Pootoogook is arguably one of the most famous Inuk artists in Canada,” I said to the crowd. “She won many prizes and was shown in national galleries, yet still lived in the street economies of Ottawa.” I paused. “Recently, her body was found in the Rideau River.” Following Pootoogook’s death, a forensic officer from the Ottawa Police made derogatory comments about her on a public Facebook post, igniting national outrage about racist Canadian institutions that have a negative impact on the dignity and lives of Inuit. News articles circulated with images of Pootoogook in the streets of Ottawa creating her drawings. These images perpetuated the white saviour mythos that follows Pootoogook’s work—a narrative that settlers project on many urban Inuit, as if to say, Look at all Pootoogook has overcome! She has been street-involved and, despite it all, possesses this beautiful, creative universe within her mind. Of course, the white saviour gaze is dehumanizing and exploitative. It’s not concerned with oh, say, organizing for the livelihood, secure housing or continued well-being of street-involved Inuit in Ottawa, including Pootoogook. The white saviour gaze is only concerned with creating a romanticized vision of Inuit artists, one they may discursively exploit and circulate forevermore, to serve their agenda of psychic conquest. Thus spoke the pseudo-logic that is white liberalism.

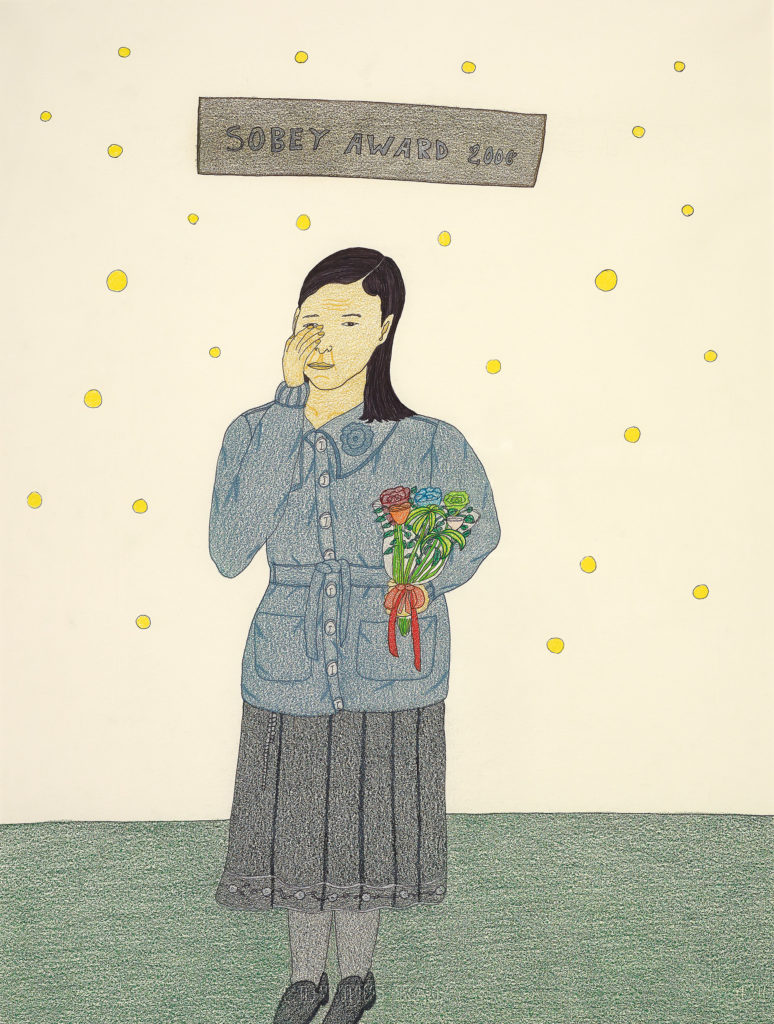

My friend, with whom I had taken my medicine break, projected an image of Annie Pootoogook’s Sobey Awards (2006) on a screen behind me as I spoke. I remember tearing up knowing there were so many Inuit and street-involved people like Pootoogook missing from the table that day. I had questions: What is reconciliation? Reconciliation to whom? Who is benefiting from all the money spent on the conference? Who does institutional reconciliation support, if not Indigenous students and other peoples most vulnerable within our communities?

These are the stories we don’t tell about Inuit art, about reconciliation, even among First Nations and Métis peoples, whom I’ve found can be ignorant about the divides between Inuit and other Indigenous communities. Because they are too dangerous to tell: the stories of exploited communities voyeuristically propped up to serve industries dominated by white people and a few good (nationalist) NDNs. Inuit have experienced exploitation by art industries since James Houston implemented the first Inuit art co-op with the intention of exploiting Inuit makers and artists for a burgeoning art industry dominated by the desires of settler collectors. Houston even handed out instructional pamphlets describing what artists should make to serve the curiosity of a voyeuristic and othering white Canadian viewer. Pootoogook loved her co-op. She talked about the co-op with warmth and generosity in an interview before her death. Many Inuit still view their co-op as supportive to Inuit makers and artists in the north of Canada. It’s important to talk about co-ops without erasing the agency and truths of Inuit who still value the system. But there is a difference between recognizing settler industry–led exploitation and erasing agency. I would argue that it’s not Inuit who are profiting most from the co-op system. This is best represented by an industry standard of not giving artists resale fees on works of sold art, a practice that overwhelmingly disadvantages Inuit working in the co-op system: only the collector and perhaps the private galleries holding the work profit, as artist and curator Kablusiak has stated.

I see the same industry cultures that formed within the co-op model in the National Gallery’s destructive history of curating a specific “look” to the Inuit art collected, and discarding anything that didn’t fit this image. And it’s not just galleries that sustain an exploitive environment toward Inuit in Canadian art industries: publications, dealers, collectors, not-for-profits and more all aid in promoting an industry standard that denies resale rights to Inuit artists. When an Inuit art figure or institution is silent about the exploitative nature of the Inuit art industry, trust that their silence is driven by self-protection. Trust that it is silent complicity. This is the legacy of Inuit art in Canada, as told through the work of Annie Pootoogook. This is the legacy we, as Canadians, as non-Inuit Indigenous peoples, must contend with. And, with Isuma representing Canada at the Venice Biennale this year, it feels important to ask if Inuit art is being jettisoned onto the international stage as a continued form of white liberal voyeurism: positioned as Canada’s pretty distractions to Trudeau’s anti-Indigenous liberal policies, meant to represent the supposedly kind and diverse histories of Canada. Is this what Inuit art is, Canada? Your pretty distraction that hides, and continues, centuries of violent colonial policies and trauma?

Back at the conference, I was still trying to get my words out. My voice was shaking. But I wanted to push forward and honour Pootoogook’s legacy and, perhaps, to implicate the Inuit art industry in Canada in Pootoogook’s death. Even if what I was about to say was dangerous. I was emotional, feeling unsafe in an environment I was told I should feel safe in, and, well, a little bit high. I never met Pootoogook but I missed her, like I miss all kin who left us too soon because of the impact of colonialism on their bodies and lives. I continued to speak about my own perceptions of Pootoogook’s life and legacy, posing a rhetorical experiment about this thing we were all there to talk about: institutional reconciliation.

“The art world was a community that well-exploited Annie…then, in turn, probably walked past her in the streets in Ottawa,” I told the crowd. I wondered how it was possible that one of the highest-grossing Inuit artists in Canada, in one of Canada’s most profitable arts industries, which contributed 87.2 million dollars to Canada’s GDP in 2015 alone, died street-involved and in poverty. Who is profiting off the Inuit art industry, if not Inuit artists themselves? Pointing to the projection of Sobey Awards, I continued, “What does institutional reconciliation in the arts mean if people like Annie can’t even access so-called reconciliatory efforts because of bureaucratic and institutional barriers? To me, reconciliatory efforts in the arts seem to be little more than lip service right now.” This was an industry utterly fascinated with the propagation of her image, of what she represented to the Inuit art industry and Canada. In Sobey Awards, she depicted Canadian publics as crowding her, viewing her through literal lenses of othering and voyeuristic pleasure. Where was the Inuit art industry when she was living street-involved in Ottawa? I believe this is an industry that cherry-picked the parts of Pootoogook’s life and work that they could exploit, without offering enough support to survive the realities they saw her living every day, in Ottawa, where they centralized the operations of the same industry that functioned to exploit her. What grounds the Inuit art industry, if not ethical and responsible relationship building with Inuit artists themselves?

Some might say that we shouldn’t talk about Pootoogook as street-involved, or about the violent way she died. Some would say that talking about Pootoogook’s life and death on the streets of Ottawa is a dishonour to her legacy and memory. But this kind of judgment, which degrades people who use substances and drink, is merely a holdover of colonial Catholicism masked as “tradition.” City-kid coping mechanisms, just like Kablusiak depicts with their soapstone sculptures. Working as a community street-outreach worker in Montreal, I met many street-involved Inuit deserving of dignity and respect. There is no dishonour in being Inuit and street-involved in a world that functions to eliminate Inuit life to make way for a colonial order. Thinking about the mind-boggling figures that went into putting on the reconciliation conference, and thinking about when I was an outreach worker and the small funds we had to stretch to support as many people as we could—to prevent the deaths of street-involved Indigenous peoples who are never present or represented in (performative) spaces of reconciliation—I would argue that the dishonour lies in industry alone. And, in the case of Pootoogook’s profound work, legacy and life, the dishonour certainly lies in the Inuit art industry.

“I implore all administrators in this room to stop caring only when we die, or when there is a flashy conference about the Indigenous topic du jour. You need to start caring now,” I finished.

This is the skewed legacy we, the next generation, inherit. How do we reconcile performative attempts to make the Inuit art industry more ethical with the fact that Inuit continue to experience economic and social disparity because of that very industry? Confronting dangerous truths means confronting an art industry, and all the actors within it, that has long been exploitative of Inuit. For “SPACETIME” editors asinnajaq and Kablusiak, Inuit futures are ensuring that all their kin’s truths are heard, and that any industry profiting from Inuit art is responsible to Inuit communities.

Annie Pootoogook, Sobey Award 2006, 2007. Coloured pencil and ink

on paper, 66 x 50.1 cm.

Collection of Paul and Mary Dailey Desmarais. Reproduced with permission of Dorset Fine Arts. Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

Annie Pootoogook, Sobey Award 2006, 2007. Coloured pencil and ink

on paper, 66 x 50.1 cm.

Collection of Paul and Mary Dailey Desmarais. Reproduced with permission of Dorset Fine Arts. Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.